The Pill

GROUP SHOW

Jan 22, 2011 - Feb 12, 2011

- SELECTED WORKS

- CURATORIAL NOTE

- INVITE

- DOWNLOAD CATALOGUE

The Pill or The Hardest Thing to Swallow

For starters, it is small and discreet. The shape of its box easily replicated a compact container of women’s make-up, which could be slipped in and out of her purse without being noticed. Once in her mouth, it can be swallowed without water.

2010 marked the fiftieth anniversary of the Pill.

That is, it marked fifty years of its use in the United States of America, as the Food and Drug Administration approved the Pill in 1960. More than half a million women were already using it to prevent pregnancies. Discovered by Gregory Pincus, a conservative catholic scientist who was looking for a way to treat infertility, the hormonal make-up of the Pill was isolated when progesterone synthesized from wild yams was injected into animals and found to decrease their number of offspring. For years, it was called a fertility treatment, given only to married women, who took the Pill in the guise of something else.

CURATORIAL NOTE

The Pill or The Hardest Thing to Swallow

For starters, it is small and discreet. The shape of its box easily replicated a compact container of women’s make-up, which could be slipped in and out of her purse without being noticed. Once in her mouth, it can be swallowed without water.

2010 marked the fiftieth anniversary of the Pill.

That is, it marked fifty years of its use in the United States of America, as the Food and Drug Administration approved the Pill in 1960. More than half a million women were already using it to prevent pregnancies. Discovered by Gregory Pincus, a conservative catholic scientist who was looking for a way to treat infertility, the hormonal make-up of the Pill was isolated when progesterone synthesized from wild yams was injected into animals and found to decrease their number of offspring. For years, it was called a fertility treatment, given only to married women, who took the Pill in the guise of something else.

And so the little Pill, which barely casts a shadow, is covered in the veil of the secrecy and intrigue of its making. With its fair share of detractors, which came from the Catholic Church and it friends, the Pill was accused of promoting immoral sexual behavior and destroying families. Entrenched in the civil rights movements of the ‘60s and ‘70s, the Pill became a symbol of moral decay for some, and social agency for others. Women in larger numbers than ever began to join the work force. It has also become a global phenomenon, where 100 million women around the world take the Pill in its many forms. And everything came together to form a delicious little bite for the media, including in cover stories for Time magazine.

And here we are in India, 2011. The population of the country is around 1,150,000,000 (1.15 billion) people. By 2030, the population of India will be largest in the world estimated to be around 1.53 billion. In 2000, the country established a new National Population Policy to stem the growth of the country’s population. One of the primary goals of the policy was to reduce the total fertility rate to 2.1 (children per woman) by 2010. The rate remains at 2.8. Population projections for India anticipate that the country’s population will reach 1.5 to 1.8 billion by 2050. India is expected to become the first and only country on the planet that will ever reach a population of more than 2 billion, which is the projected population by the end of this century. The need for education and access to birth control seems to be as great a necessity as ever in the subcontinent.

Dr. Mohan Rao of Delhi’s Jawarlal Nehru University suggests that the Pill hasn’t achieved popularity among Indian women because of their impoverished state. “Our average woman is not suited for the pill; she is hungry, she is anemic and has an extremely low BMI. Above all, she has no access to medical care. It’s also likely that her husband decides on contraception,” says Rao. Illiteracy and ignorance are also factors, and sterilization remains India’s most common contraceptive method.

So where do we wave this universal flag of Feminism, which lies limp under the weight of global inequality?

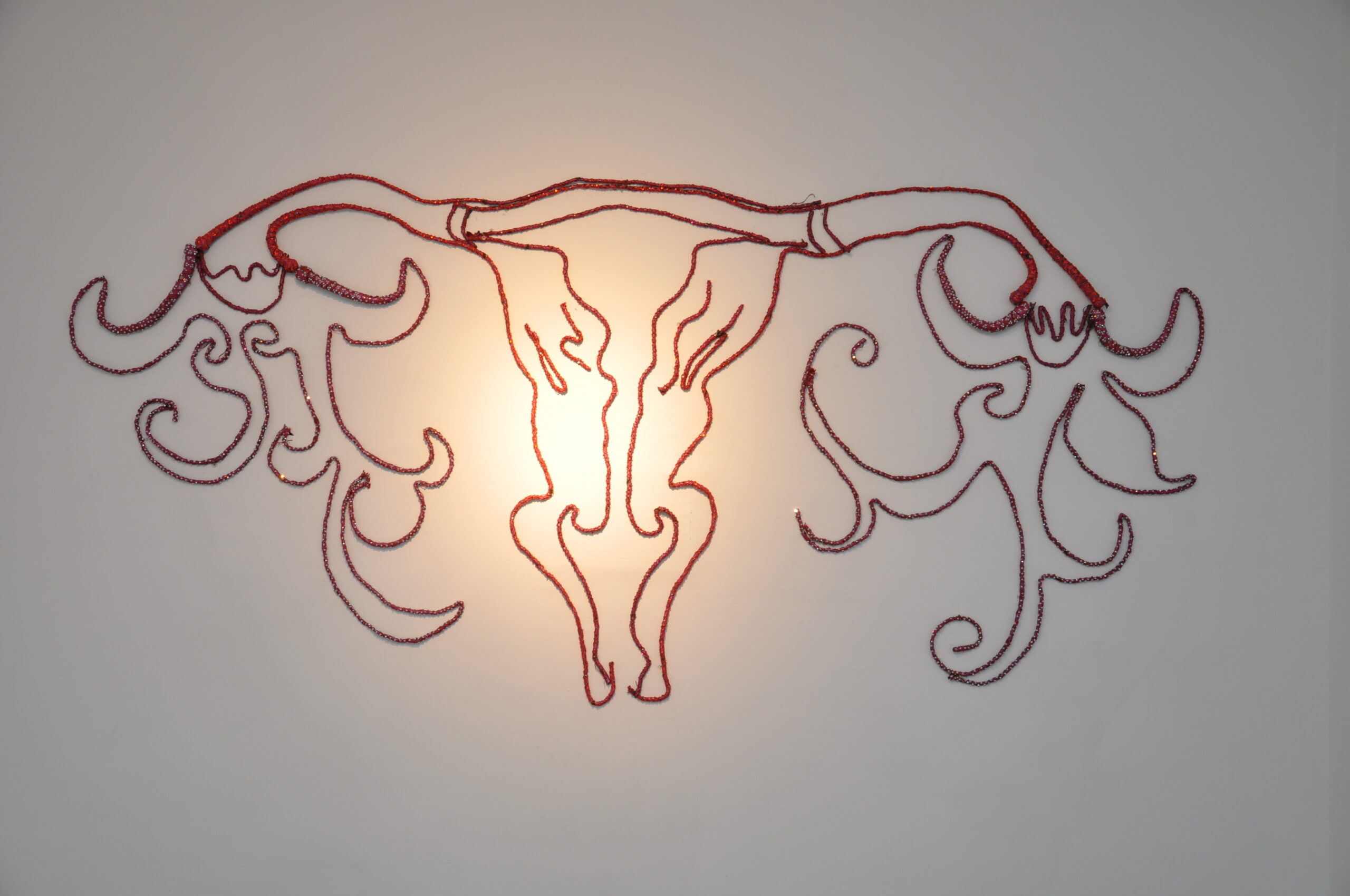

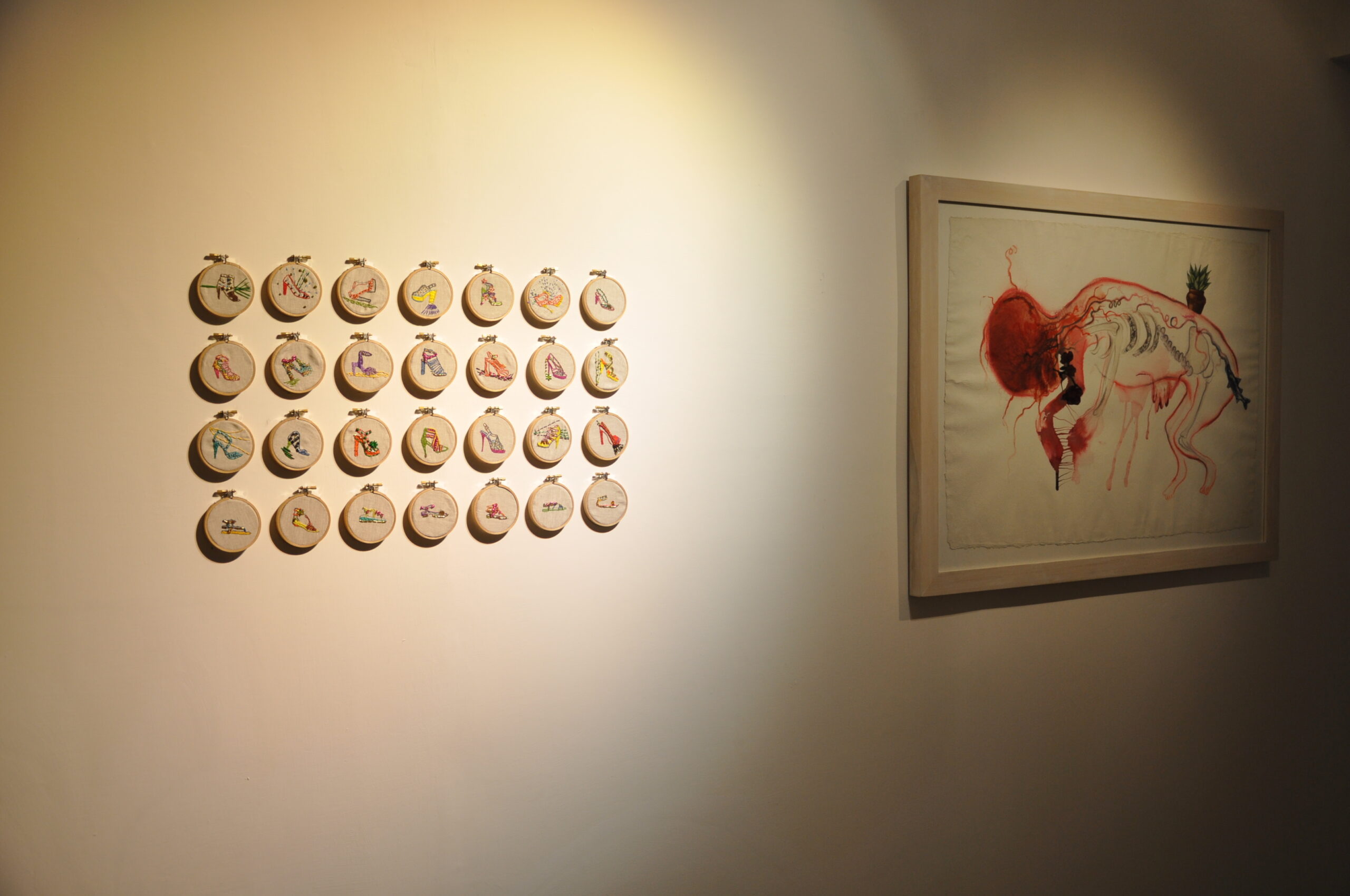

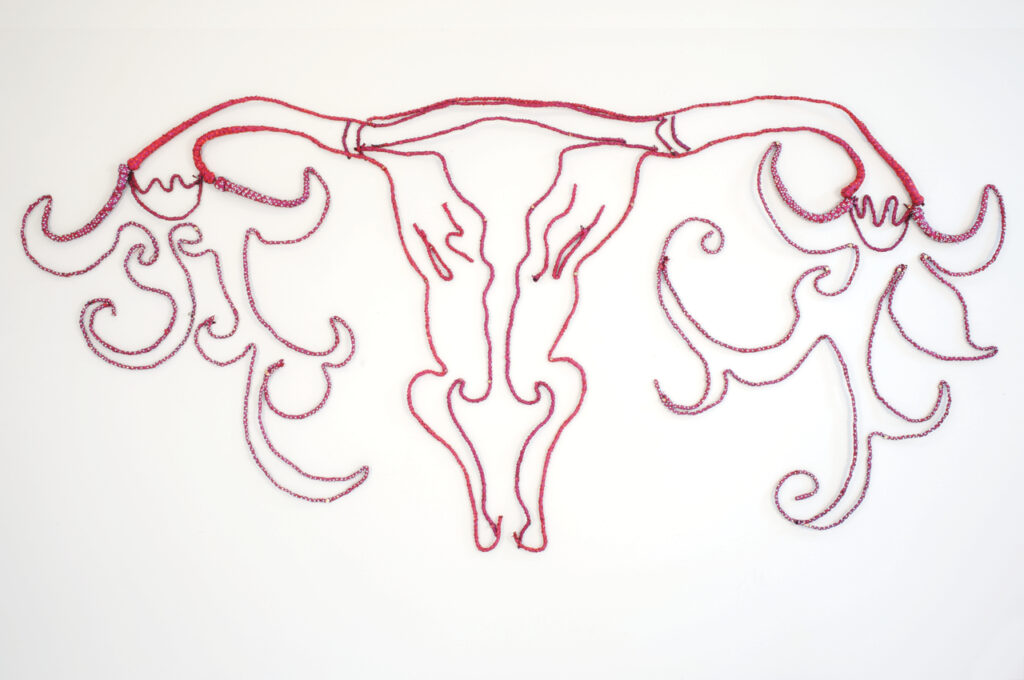

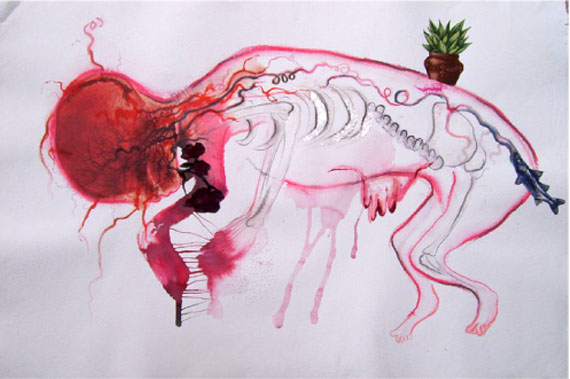

For artist Jaishri Abichandani, the distance between home in India and her current residence in New York draws a relationship between the body and longing. In No Way Home (2010), a magnetic wall hanging made of pink leather and jewels references a uterus, an Indian holy cow and a steer from the imagined Wild West. Swati Khurana’s practice has been informed by the Pill for many years, as her work Family Planning (2001) will attest. Khurana’s recent Monthly Cycle (2011) repositions her engagement with the Pill, focusing on its daily ingestion through an embroidery project in which she collaborates with her mother and grandmother.

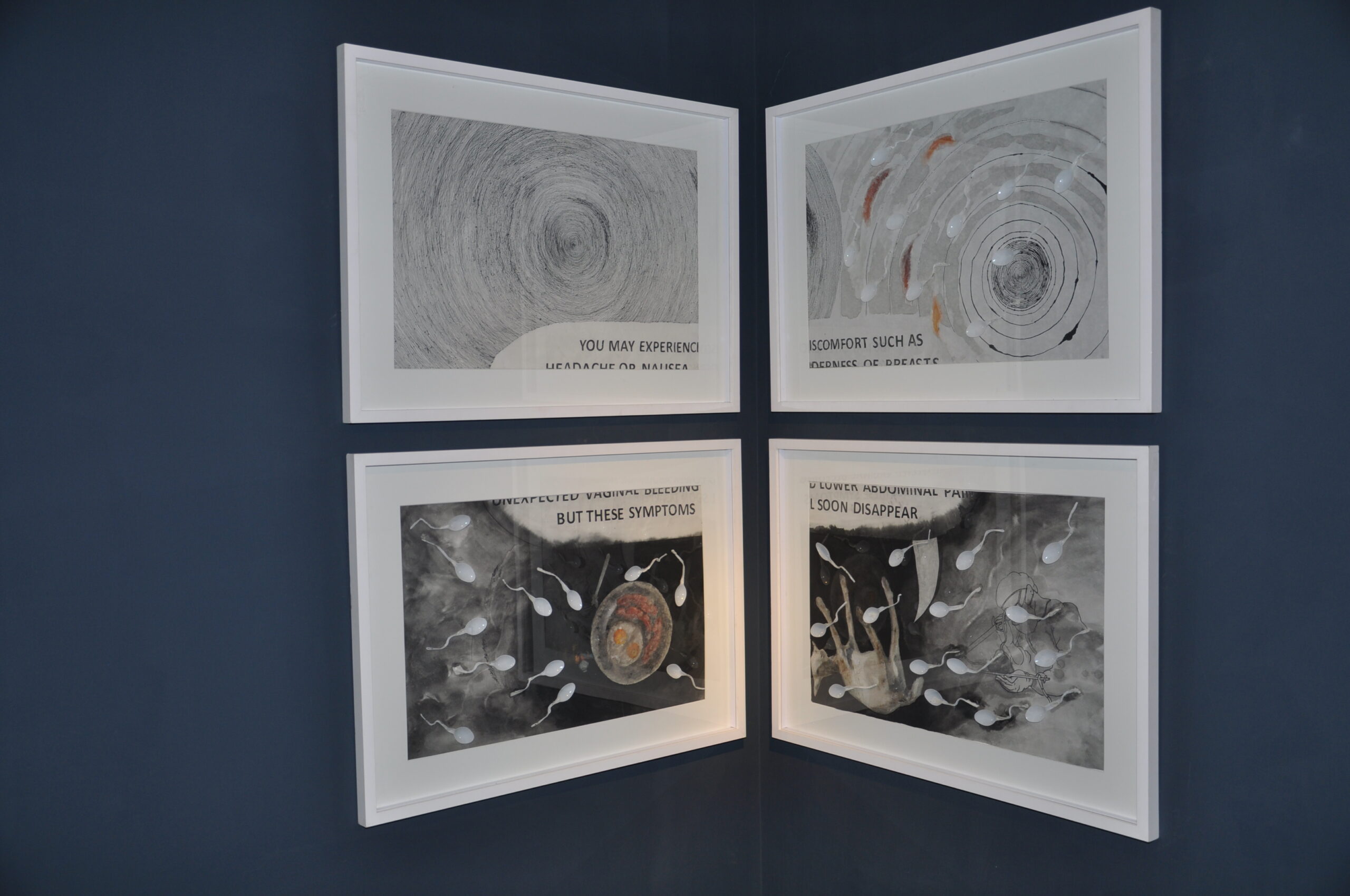

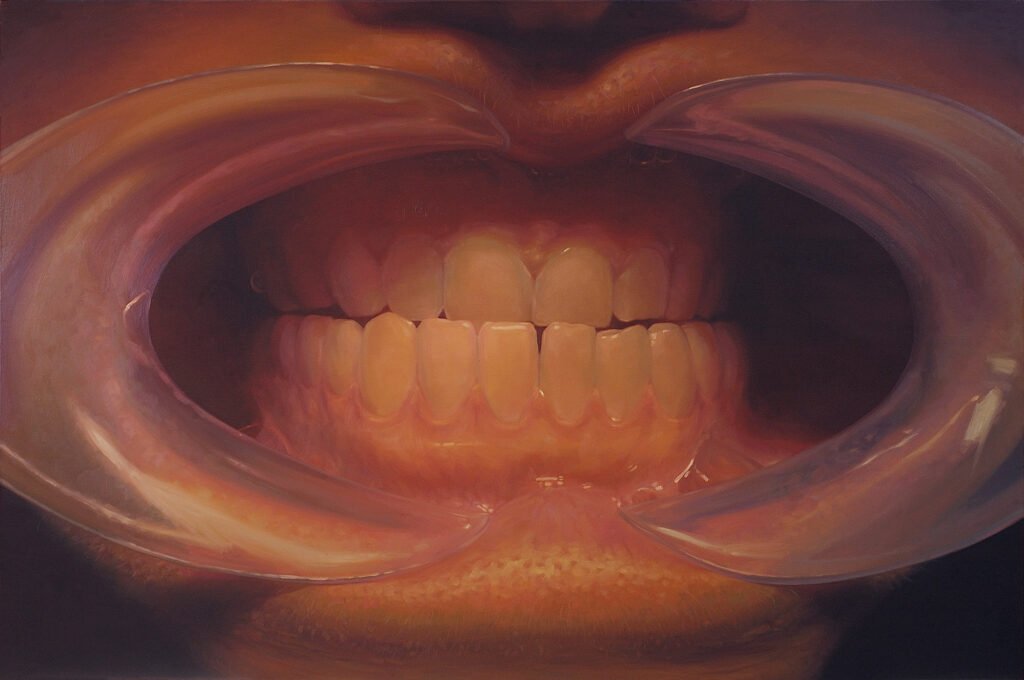

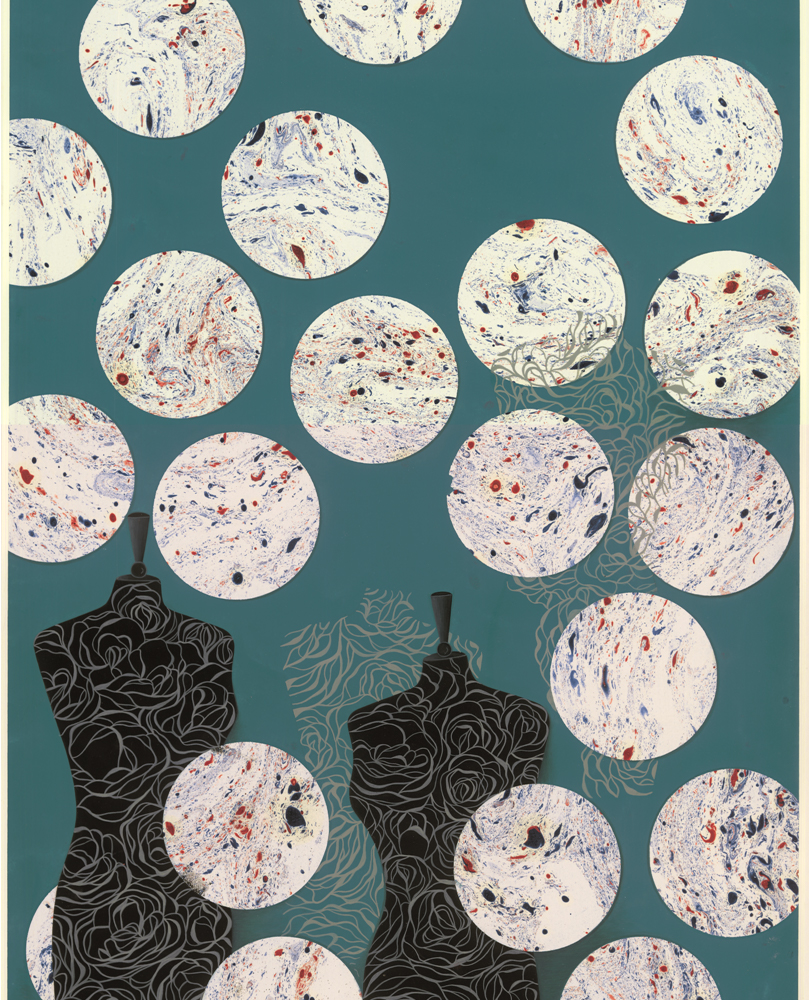

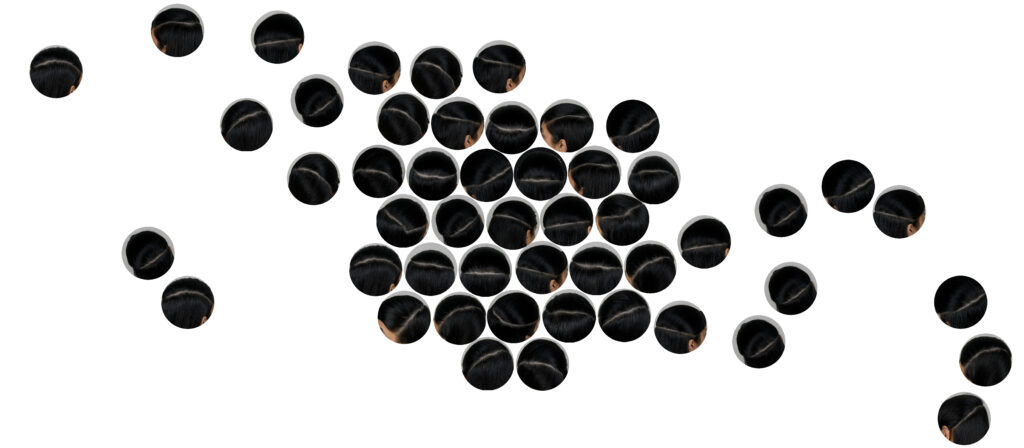

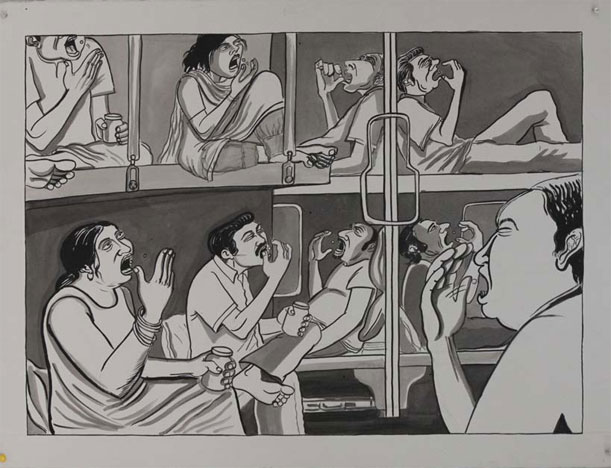

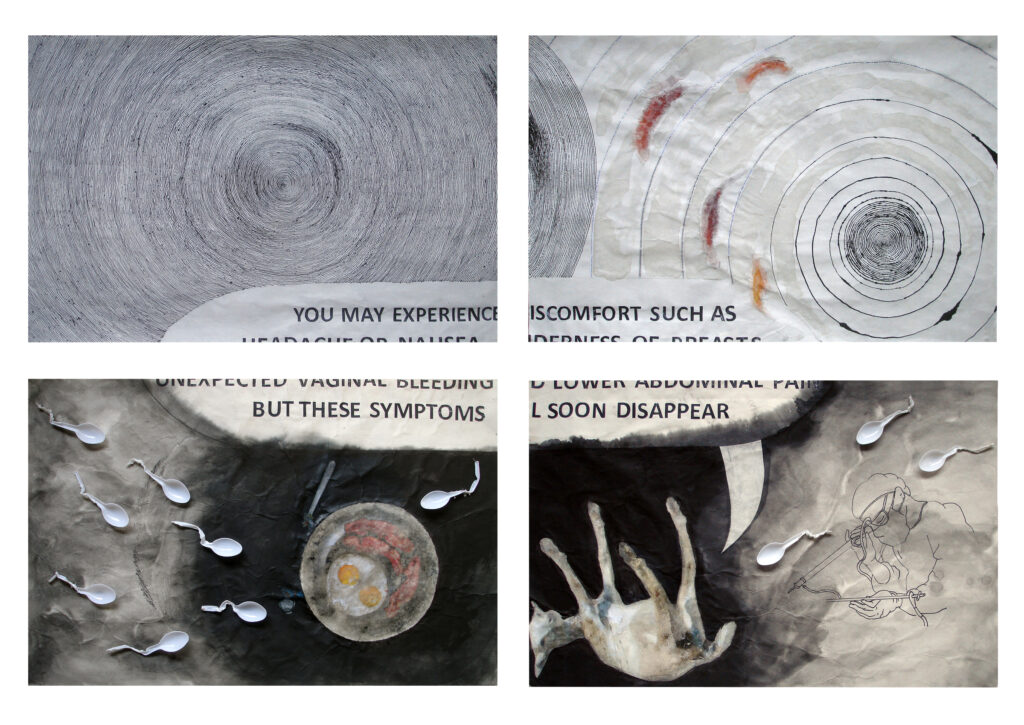

Seriality of a different kind enters into Kaif Ghaznavi’s Maang. Ghaznavi considers the measure of cycles in rural villages where women follow lunar patterns of understanding time. She maps out this passing of time and space throuhg circular rhythms that elide linear duration, in an esoteric charting of the body. Abir Karmakar focuses on the oral references of the Pill, magnifying mouths in highly sexualized terms.

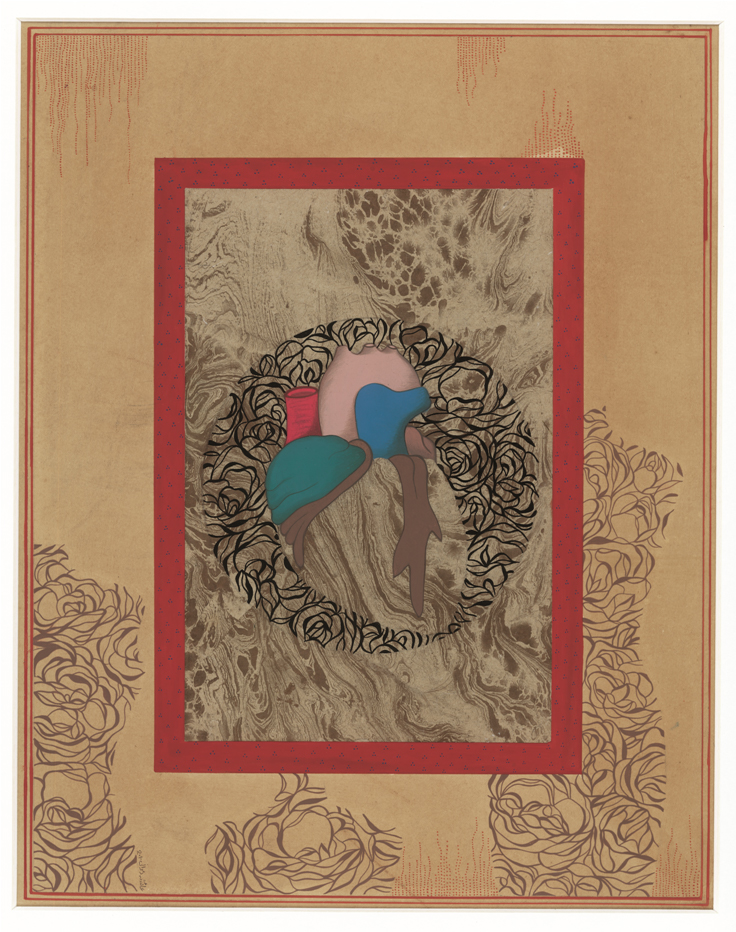

Ayesha Durrani, from Pakistan, uses the forms of mannequins join binary opposites, like hard and soft, and animate and inorganic. Her work reveals the difficulty in categorizing and manipulating the female form. For Tazeen Qayyum, hot water bottles, a popular signifier for menstrual pain, become the support for her superbly detailed miniature paintings. Qayyum transforms these bottles into painted objects, investing them with a personalized form of remedial power.

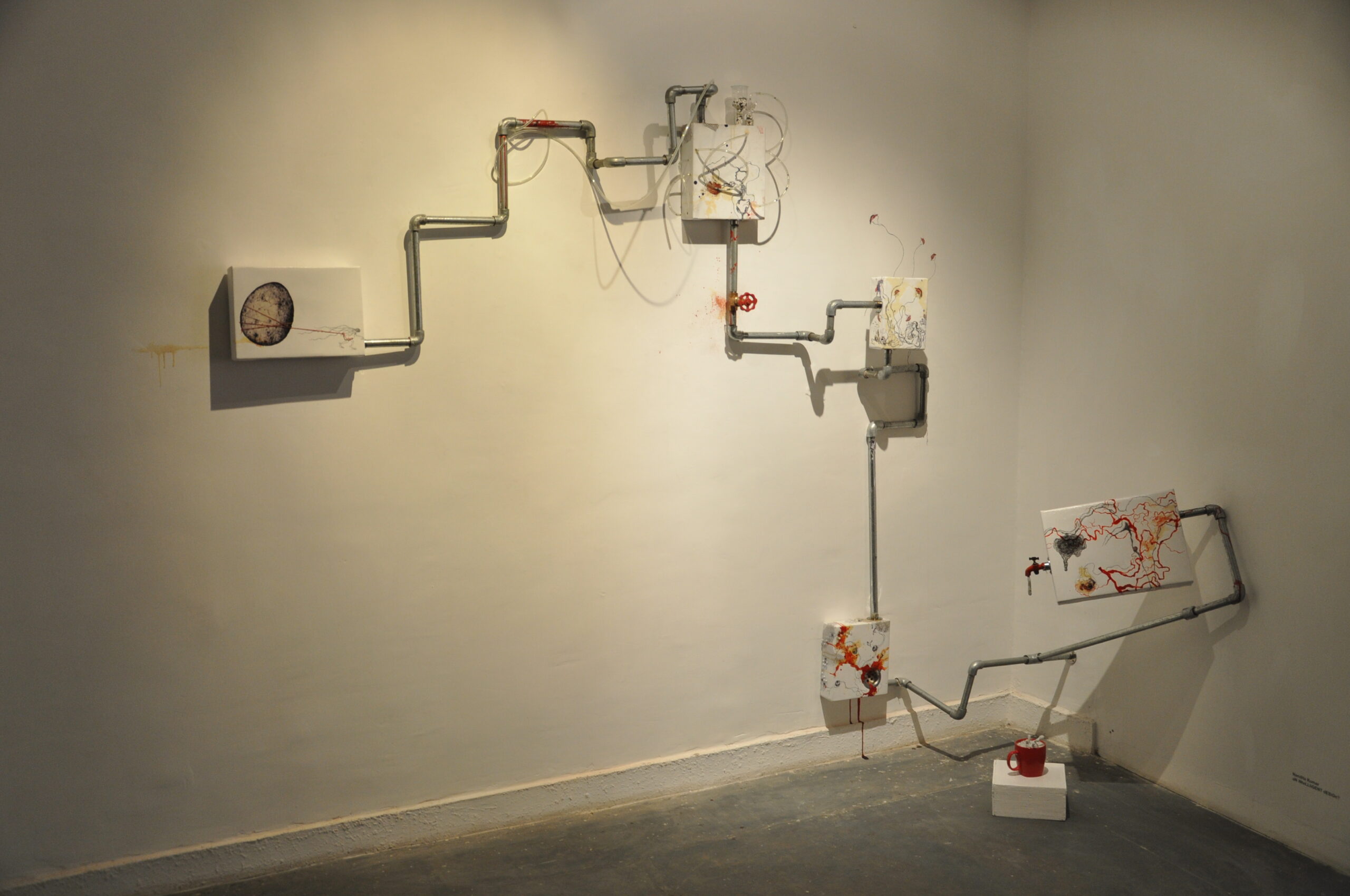

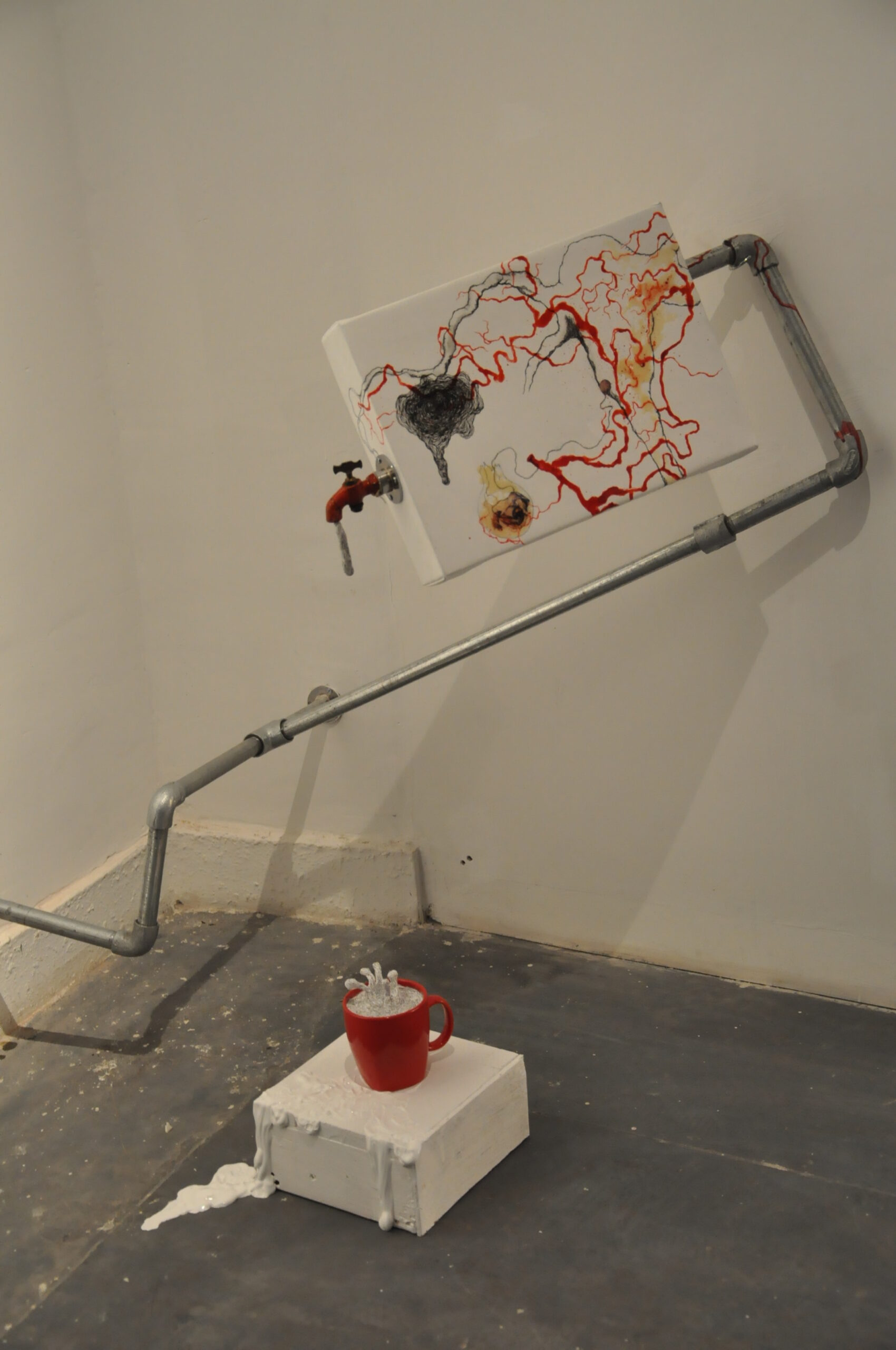

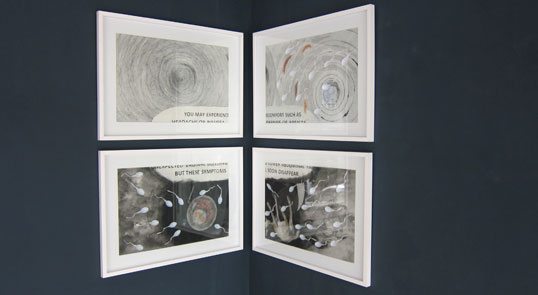

As we encounter the larger concerns surrounding the Pill, it becomes immediately apparent that its magic has been as deeply mythologized under the banner of feminism as its shortcomings have been by its opposition. Tushar Joag considers the real side effects of the Pill, which are part of an ongoing battle for the bodies of women, and which is symbolic of larger societal questions regarding the inscription of laws on people. Sarnath Banerjee questions the promise of the Pill, pointing out its dangers and inefficacy in an intervention into the show’s curatorial note. Nandita Kumar uses the idea of plumbing to suggest a satirical view of understanding the Pill and its effects on the body.

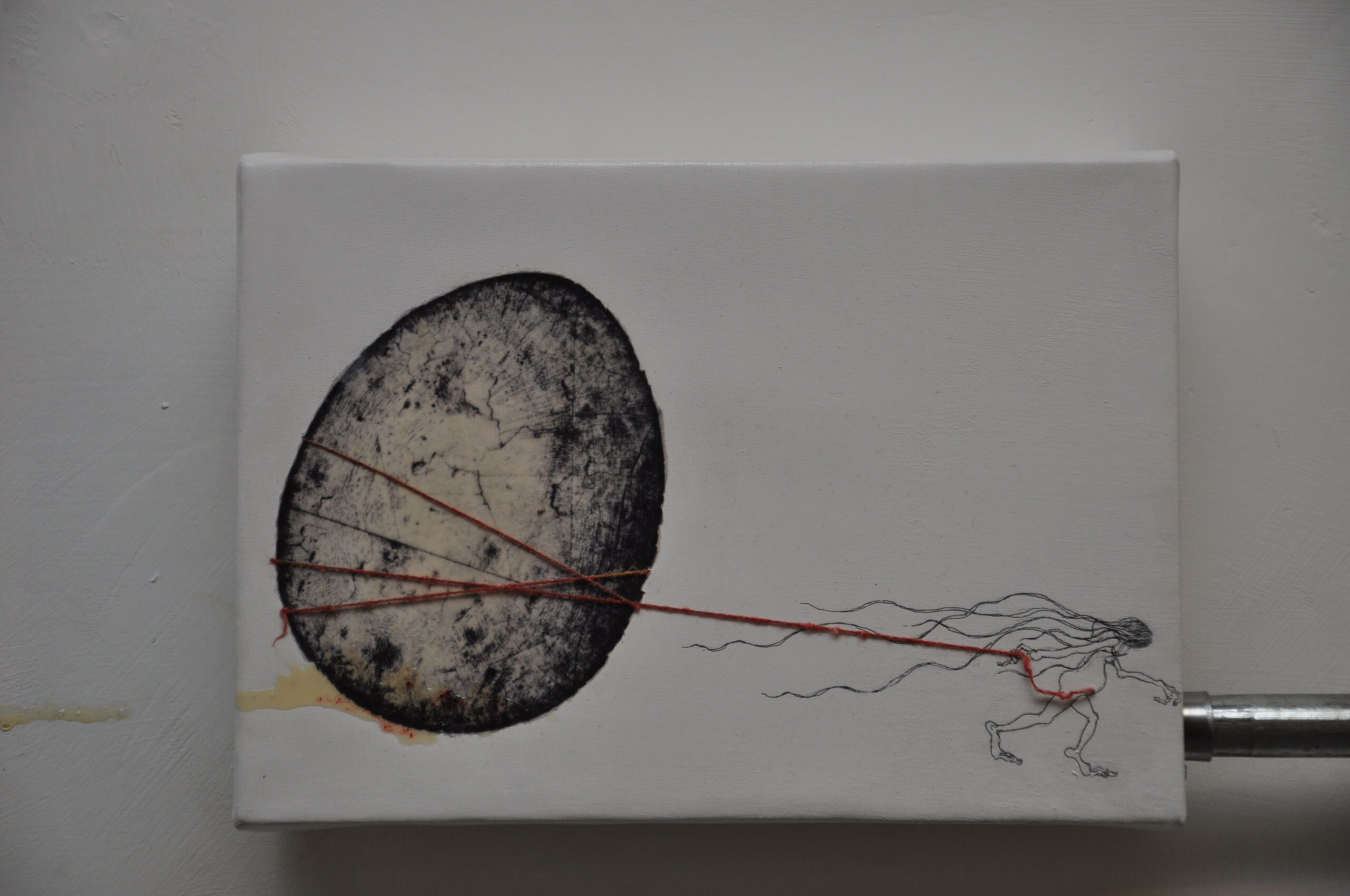

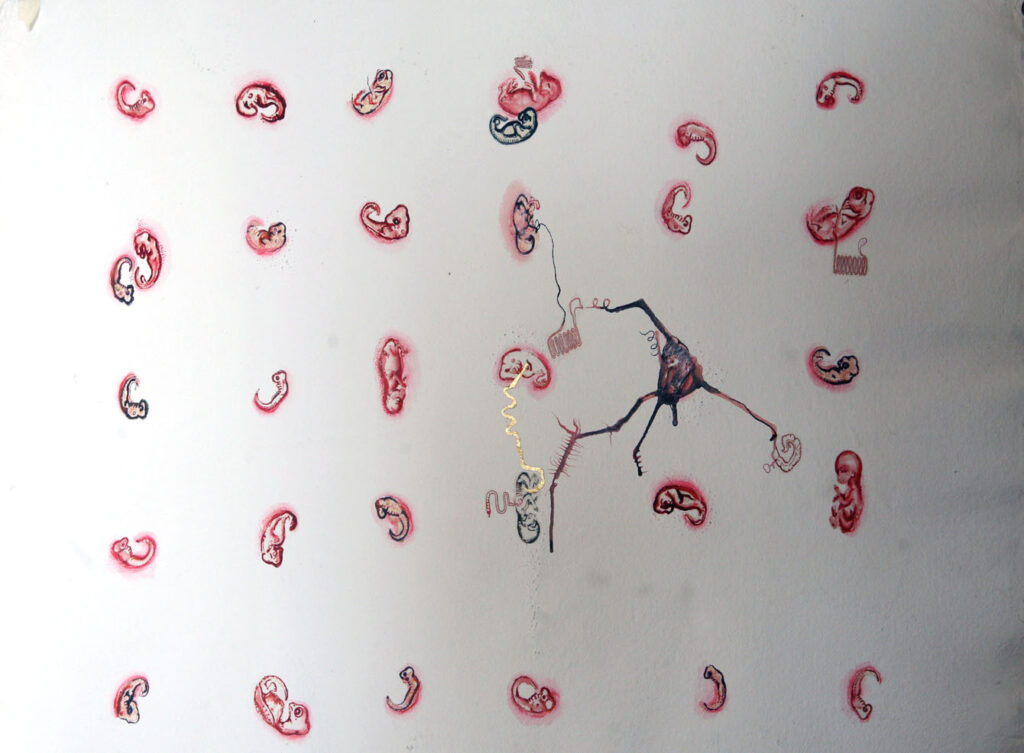

The Pill, as an icon for the modern woman, has an exclusionary aspect in that it presupposes a monogamous sexuality, performed by a man and a woman. A categorical acceptance of the Pill as a the most important discovery of the last century would not be compelling in terms of the global dilemma of many deadly sexually transmitted diseases. It would also be assuming a constituency that is heterosexual, educated and affluent. For photographer Vito Tumbarello, Chloe, a drag queen in the middle of undergoing a transformative sex-change, was the perfect subject to highlight this dissonance. How does the Pill affect Chloe? What other health concerns and realities might exist for her, in a space that is non-normative in terms of gender and sexuality? Mithu Sen’s Kill Pill (2011) was drawn as a commentary on infertility, and poses a question of the potential of life and death tethered to the Pill.

The politics of the Pill are deeply informed by lobbies, which either reify its promises or magnify its side effects. Funded by corporate pharmaceutical interests, which can achieve hegemonic control over the media and public opinion, the politics around the Pill are not only about health and reproduction. There are financially driven decisions made regarding its relationship with public opinion.

Perhaps the one point that cannot be argued is simply that the Pill is an icon. Its circulation in language might be the best proof of this. It is described as magical, innocuous and terrifying, a set of three words that are difficult to level.

It is always capitalized. Like Madonna. And God.