Sacred/Scared

GROUP SHOW

Feb 1, 2014 - Mar 5, 2014

- SELECTED WORKS

- CURATORIAL NOTE

- INVITE

- PRESS RELEASE

- DOWNLOAD CATALOGUE

The title of this exhibition stems from a deliberate typographical error. If you were to type the word ‘sacred’, the computer often auto-corrects it to ‘scared’. Is this merely an accident or does it point to a symptom of our times? In liberal circles, and especially in the art field, the sacred is looked upon with a measure of healthy skepticism and bracketed within forbidding connotations. It is either relegated to the domain of ancient or traditional art or Indological research, or is seen as a source of inspiration for certain kinds of abstractionist tendencies within the regional modernism that developed between the 1950s and the 1980s. The sacred is also often reductively identified with the dogmas of organized religion. It can also, and misleadingly, be conflated with an aggressive revanchist ideology based on the politicization of religious identity. The justified fear of the liberal and secular intelligentsia, artists among them, for such an ideology – with its attendant threats of violence, censorship and a monochromatic, authoritarian world-view that suppresses diversity – translates as a rejection of the sacred. This has also been the experience of intellectuals and artists in many other societies in transition, where the trajectory of modernity has been set against all expressions of what appears to be an undead, vampire-like past that continues to press its claims on the present.

However, the sacred cannot be reduced to dogma or conflated with an ideology of politicised religiosity. This exhibition will address the rhetorical, ludic and performative strategies through which artists have sought to account for the ways in which the sacred leaks into the world and the social, cultural, political and psychic domains it inhabits. The sacred is not a pre-ordained and pre-shaped entity. It is an auratic, liminal condition, a tantalizing horizon and a place where you find yourself without looking for it.

CURATORIAL NOTE

Sacred/Scared

A Lexicon of What It’s About and What It’s Not

Nancy Adajania

*

Ambivalence

The title of this exhibition encodes a moment of typographical uncertainty. If you were to type the word ‘sacred’, the computer often auto-corrects it to ‘scared’. Is this merely an accident or is it symptomatic of a deep anxiety and debilitating ambivalence of our times? In liberal circles, and especially in the art field, the sacred is looked upon with a measure of healthy scepticism and bracketed within forbidding connotations. Often, it is relegated to the domain of ancient or traditional art or Indological research, where it can be domesticated within a tradition of pedagogy and interpretation. Or then, it is seen as a source of inspiration for certain kinds of abstractionist tendencies within the regional modernism that developed in this country between the 1950s and the 1980s; here, too, the sacred can be tamed within the discourse of a self-reflexive modernism appropriating impulses from the past into its dynamic present.

Organized Religion

Most typically, the sacred is reductively identified with the dogmas of organized religion. In this vein it can also, and misleadingly, be conflated with an aggressive revanchist ideology based on the politicization of religious identity. The justified antipathy that the liberal and secular intelligentsia, artists among them, harbour towards such an ideology – with its attendant threats of violence, censorship and a monochromatic, authoritarian world-view that suppresses diversity – can all too often translate as a thoroughgoing rejection of the sacred. This has been the experience of intellectuals and artists in many other societies in transition, where the trajectory of modernity has been mapped against all expressions of what appears to be an undead past that presses its unwelcome claims on the present.

Resistance

However, the sacred continues to resist all such categorizations. It cannot be reduced to dogma or conflated with an ideology of politicised religiosity. This exhibition addresses the rhetorical, ludic and performative strategies through which artists have accounted for the sacred as it leaks into the world, and the social, cultural, political and psychic domains that it inhabits. This exhibition embraces the various and sometimes contradictory gestures by which the sacred may be approached. It is phrased as an inquiry, and raises questions that are not asked for fear that one may be misunderstood, or for reasons of self-censorship. It investigates the substrata of a condition that is both elusive and present; that is claimed by numerous public manifestations yet remains intimate, unclaimable, pluriform.

Memory

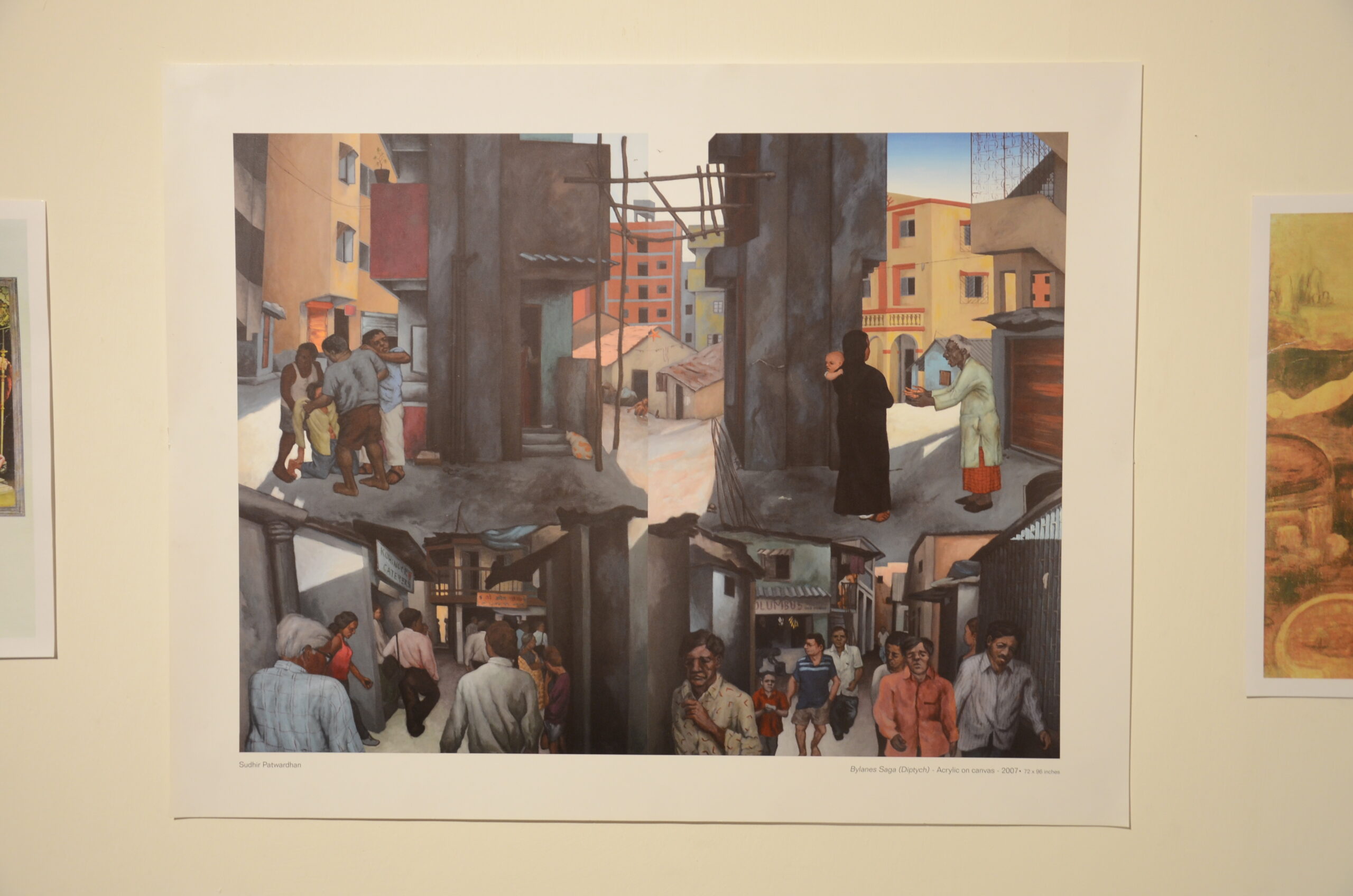

I have gathered together a varied typology of materials here, ranging from paintings, photographs, films and videos, to mixed-media works and sculpture, to children’s drawings. Discreet reproductions, incorporated into the flow of the exhibition as pedagogic annotations, are intended to prompt the viewer into an awareness of the unacknowledged histories of Indo-Iberian modernism (Angelo da Fonseca) or the epiphanic re-reading of a contemporary work that appears to have settled into a stable meaning within the interpretation of the artist’s work (Sudhir Patwardhan).

Turbulence

I also include, as a key work in this exhibition, Tyeb Mehta’s mesmerizing 1970 film, Koodal, made for Films Division and rarely shown: Koodal brings the turbulent energies of religious belief and civic expression into surging collision, proposing the portrait of a two-decade-old postcolonial nation in the throes of transition. Engaging in dialogue with Koodal are Tushar Joag’s video meditations on the schismatic communally oriented politics of the 1990s and early 2000s, Phantoms (2002) and Three Bullets for Gandhi (2007).

Colloquies with the Icon

The icon is perhaps the most readily available and widely accessible interface with the sacred. By definition, it offers itself as a visible and relatable form of the otherwise unapproachable sacred. Embodying superhuman qualities of perfection, power and eternity, it serves as a focus for the aspirations and yearnings of the faithful; it acts as a guarantee, variously, of intercession, healing, redemption or consolation. And yet, given its location within a body of rituals and a system of ceremonial, the icon can paradoxically become remote from the world of affect that the worshipper inhabits. Under the ministrations of organized religion, it can become fetishized, and can intimidate or even alienate the worshipper through exaggerations of scale.

N Pushpamala, Angelo da Fonseca and Veer Munshi approach the icon from distinctive ideological commitments, but all of them hold colloquy with the icon. They reclaim the icon for the world of affect and criticality, for the circulations of human tribulation and exaltation, using humour, wisdom, wit and emotional tenderness.

An atheist who equates religion with folklore, N Pushpamala explores what she terms the sociology of folklore. Her photo-performance, ‘Our Lady of Velankanni’, appropriates the form of Mary known to the faithful as ‘Our Lady of Good Health, the Blessed Virgin Mary of Velankanni’, transporting it from the domain of contemporary Catholic votive imagery into the space of fiction and theatre. Collaborating with Clare Arni, Pushpamala produces a tableau in which the two artists appear as angels paying playful obeisance to the Virgin and Child. Credited with healing powers, the Velankanni shrine attracts large numbers of Hindus, as well as Muslims, in addition to Christians; indeed, it represents a Christian practice with strongly syncretistic features, which has evolved from the encounter between European Catholic tradition and Tamil devotionalism.

While Pushpamala is not a believer, she is not an iconoclast either. Even as she subjects the conventional image of the beatific mother and child to ironic scrutiny, she recreates the popular aesthetic of the votive with affection. We need not be trapped in the binary between iconolatry and iconoclasm, there is a field of displacements, translations and transfigurations between these two poles that Pushpamala investigates.

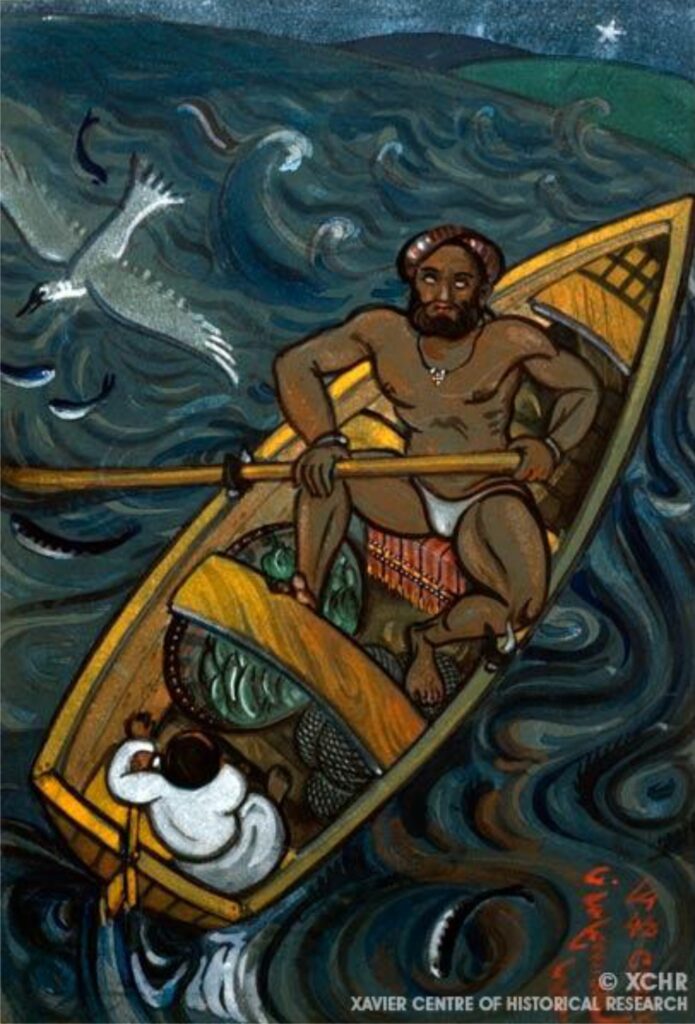

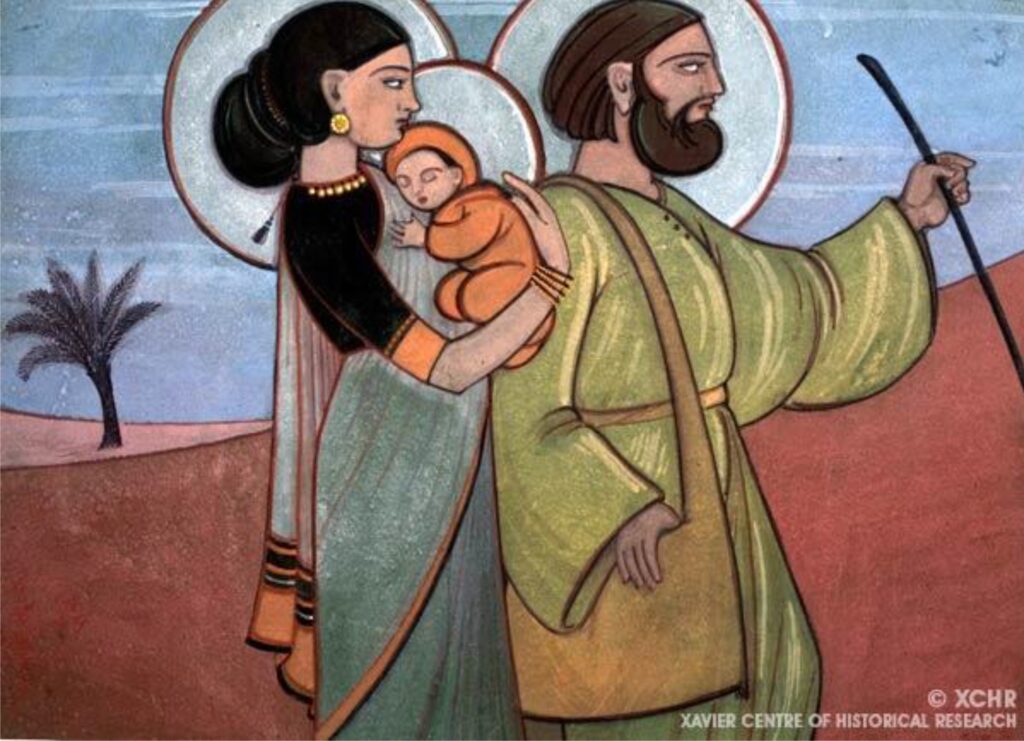

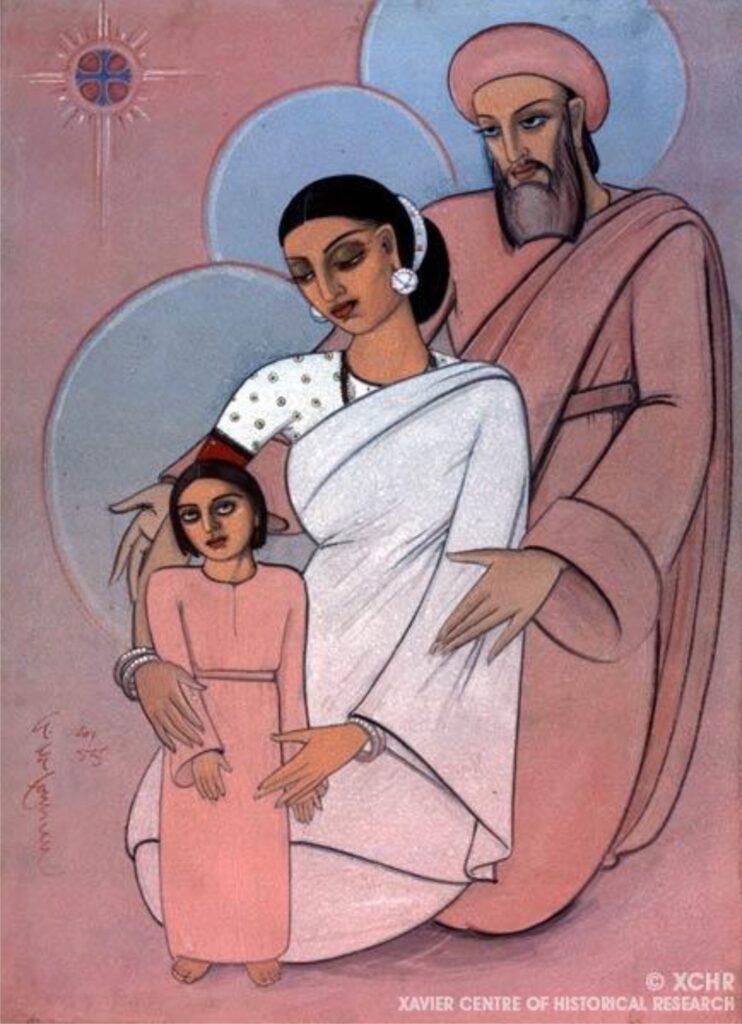

The Goan artist Angelo da Fonseca (1902-1967) is an unknown and unacknowledged pioneer of decolonization, both in Indian art practice, as well as in the iconography of Indian Christianity. He was the first modern Indian Christian artist to translate the narratives of Christ’s life pictorially in an indigenous pictorial vocabulary. Unlike, say, some of the late Mughal artists as well as his fellow modernist Jamini Roy, who were Muslims or Hindus, presenting Christian images in Indian accoutrements, Fonseca worked from within Christianity as a believer addressing both his own community or fellow-believers, as well as the Indian audience at large.

Da Fonseca’s was a courageous choice; isolation and humiliation, as well as bafflement and indifference came his way. To the end, though, he remained inspired by his conviction that Christianity could not be trammeled by the aesthetic preferences associated with European colonialism and that its spiritual teachings and examples should become available locally in terms consonant with local culture. His sari-clad Madonnas, baby Jesus in the aspect of infant Krishna and his angel-apsaras and gandharvas were mediated by the Bengal school heritage of Santiniketan where he studied under Nandalal Bose. Significantly, his work anticipated by decades the official doctrine of ‘inculturation’ endorsed during the Second Vatican Council (1962-1965) in recognition of the necessity of decolonization for a global church.

Fonseca’s compassion and radical desire to break down religious boundaries converges in Veer Munshi’s ‘Hamara Hanuman’ (2009). The artist M F Husain, the protagonist of ‘Hamara Hanuman’, is shown here not as a fleeing refugee forced into exile by the persecution unleashed by the fascist forces. Instead he is imagined as a figure of superhuman power, indeed as Hanuman, the beloved figure from the Ramayana, a devotee of Ram who participates in the conquest of Lanka and the rescue of Sita, and also, locates and brings the life-giving herb Sanjivani for Lakshman. The Husain/Hanuman composite carries symbols associated with Husain’s art, the long brush and the Petromax lamp. Munshi employs irony to devastating effect. The Hindu Right wing charge against Husain was that he had profaned the images of Hindu deities by creating modern expressionist versions of them and by implication that Muslims had no right to access the reservoir of Indic imagery.

Exorcising Phantoms

The sacred, as a mode of contested continuity with a past that is at once both actual and imagined, can inhabit the individual imagination and shape the construction of collective memory in spectral ways. The sacred can manifest itself as a troubling fragment or figment that refuses to be assimilated into a coherent narrative of selfhood. It can prey on the mind as nightmare, as repressed content emerging to view. It can haunt the sensibility as a series of phantoms, palpable enough to exert psychological pressure yet too diaphanous to be grasped and called to account. The phantoms of the sacred can generate anxiety, vertigo, delirium and terror. They threaten the self’s stability and consistency; they prompt a questioning of religious and ethnic foundation myths; they decoy the self into pursuing them in various directions.

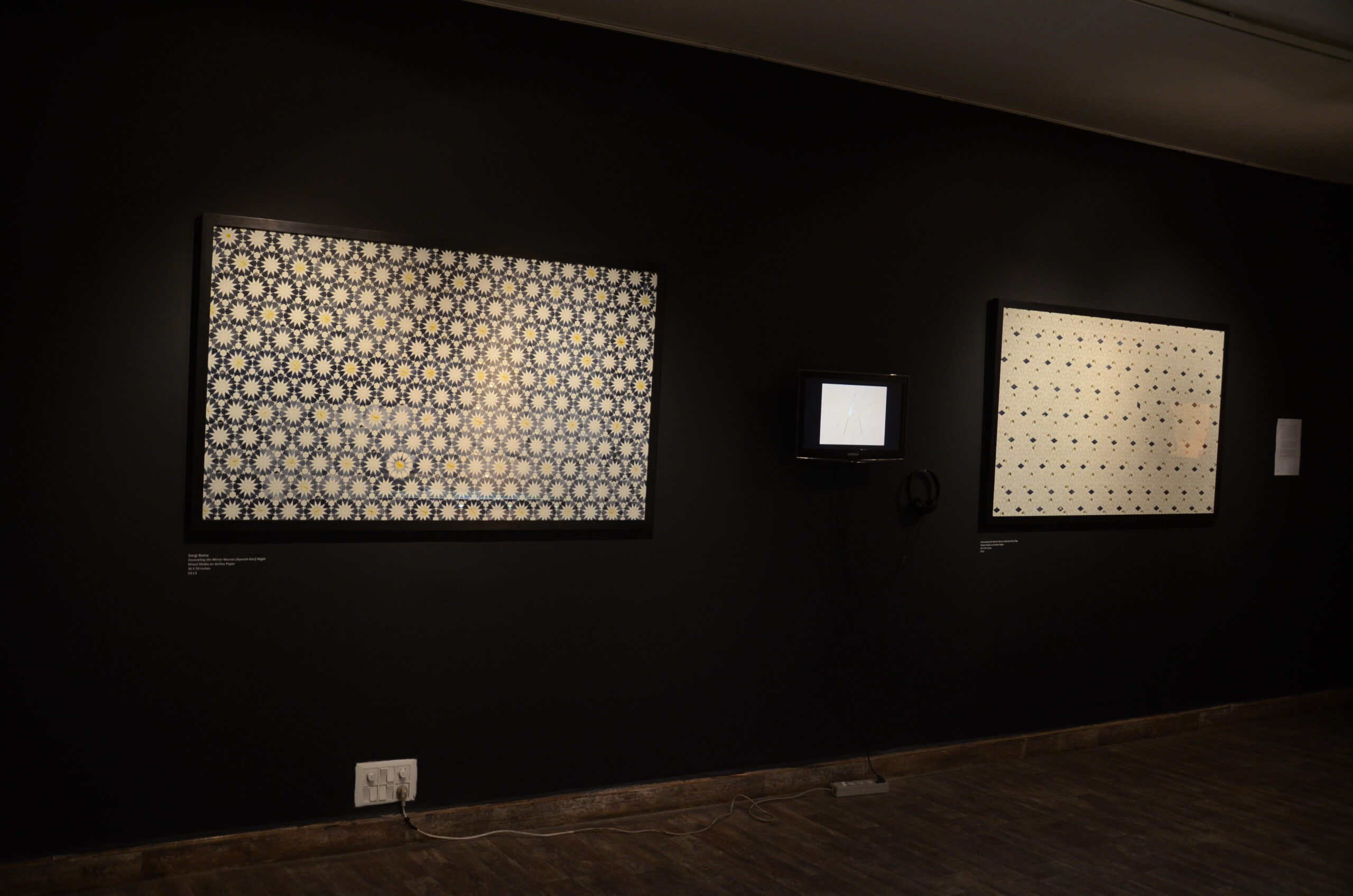

Tyeb Mehta, Tushar Joag and Gargi Raina conduct courageous inquiries into the pivotal role that the phantoms of the sacred play in India’s charged social and political climate, where communities that have lived together in peace for generations can be manipulated at shockingly short notice into annihilating one another.

Tyeb Mehta’s Koodal is electric with the phantoms of the Partition, religious schisms, incipient class warfare and gender irresolutions: a dance of polar opposites approaching each other, pulling away, caught in a cycle of confrontation and reconciliation. Edited to a percussive score by Narayana Menon, the film is a study in a restless kinesis: bodies locked in a kabaddi bout, mating bulls whose end is foretold on the hooks of the abattoir, the surging crowds attending Gandhi’s funeral cortege, the self-flagellating street acrobat and the transgender performer painting his/her face into a mask. The artist once observed: “Koodal is my autobiography”. As a South Asian Muslim, Mehta was seized by the crisis of negotiating a form of belonging in a turbulent post-colonial India. The film ends with a ritual of reconciliation – the re-enactment of the sacred marriage of Shiv and Parvati in the Meenakshi Sundareshwara temple, in Madurai – to exorcise the phantoms of violence and point idealistically to more harmonious forms of communion and collective being. The title of the film – the Tamil ‘koodal’ variously means a meeting point, a gathering for a general assembly, or sexual union – emphasises Mehta’s deep-seated need to overcome the fragmentation in his consciousness.

Tushar Joag’s videos, ‘Phantoms’ (2002) and ‘Three Bullets for Gandhi’ (2007), made more than three decades later, continue this viscerally charged enquiry into the disquiets of a post-colonial nation-state. Joag’s videos are held hostage by revenants. Who are they? Unassuaged ancestral spirits: spectres of unachieved futures, or unnamed, unclaimed victims of riot and pogrom. Joag’s crisis as artist and as citizen hinge on his self-questioning on the subject of being a member of the Brahmin elite within India’s Hindu majority; how do these circumstances of birth align him to various histories of privilege, oppression and Hindu sectarianism.

In ‘Phantoms’, made in the aftermath of the Gujarat pogrom in 2002, which resulted in the death and displacement of hundreds of members of the Muslim minority, he mounts a search for his kulavrutant or family history. Joag is critically aware that he belongs to a caste group (the Chitpavan Brahmins) from which the forces of Hindutva have for generations recruited its leading members; among them, the Mahatma’s assassin Nathuram Godse and the right-wing ideologue V D Savarkar. ‘Three Bullets for Gandhi’ stages a grotesque and terrifying performance analogue of Gandhi’s assassination in a Bombay underpass. The video begins with the image of the Mauryan lion capital, the official symbol of the Indian republic. From this sacrosanct symbol encoding an ethical mandate of liberty, equality and inclusiveness, Joag himself appears as a man-lion, a figure of violent almost erotic provocation, alluding to the subversion, indeed the perversion of modern India’s foundational charter.

Gargi Raina’s ‘Excavating the Mirror Neuron (Ayeneh-Kari) Day/Night’ (2013), an exquisite pair of mixed-media works and an eponymous video, employ the patterns of sacred geometry as a device to centre the self, but also to forge a sense of interconnectedness with others. The paper surface of the works is shot through with diamonds of light reflecting off the mirror beneath it. The ‘mirror neuron’ in the title alludes to the artist’s belief that, despite irrevocable violence, an invisible thread of shared empathy connects Kashmir’s Hindus and Muslims across the divide of religious difference. While the mirrored light is a homage to ayeneh-kari, the scintillatingly beautiful mirrorwork found on the walls of mosques, mazars and shrines that the artist visited in Tehran, the layers of light and opacity, reflection and refraction signify Raina’s struggle to dialogue with the ghosts of history.

The artist, a Kashmiri Pandit by birth, has to contend with the multiple experiences of exile into which members of her community have historically been forced, the latest displacement caused by the conflict between Islamist militancy and the Indian state, which tore Kashmir’s complex social fabric apart during the 1990s. Raina inserts a videographic probe into the certitudes of sacred geometry, to expose the unmarked graves of the militants. Her work recalls to mind the Sufi parable that pictures the truth as a broken mirror, its thousand shards telling a story from every perspective.

Sensing Allegory

Allegory is the narrative that travels in disguise, in camouflage. Its surface lends itself to reading while its depths remain hidden behind encryption; but often, the key to the code is left lying in plain sight. Allegory reminds us that the sacred is often to be found at the heart of the everyday, in the textures of speaking and living; that it suffuses the fragments of half-forgotten scriptures, informs the protocols of encounter between strangers and dialogue between friends, active wherever a distance has to be covered between one imagining, desiring, dreaming self and another. Allegory can also cross the distance separating two epochs or cultures, marking the persistence of a tradition originating in one time and place in a completely distinct location.

Sudhir Patwardhan’s paintings often evoke the life of the small town or shanty, coping with the crises of late-industrial society; his protagonists are the marginal denizens of the street, the store, the factory and the Bombay-Thane commuter train system. Looking closely, however, we are sometimes intrigued, then amazed to find that his characters might engage one another in the manner of figures in a Gothic altarpiece or a painting from the Northern Renaissance, and their local gestures and costumes conceal scenes from the life of Christ.

The diptych ‘Bylanes Saga’ (2007), for instance, plunges us into a dystopian late-industrial townscape. Its three main tableaux are drawn from everyday life; beneath their workaday surfaces, they crackle with tension. A Muslim woman holds on to her child, not yielding it to an old man who seems to ask for it. A man has slumped to his knees; have the men who surround him rushed to his rescue, or did they knock him down in the first place? At the centre of the composition is a clearing, a rare open space in a contemporary Indian town; a forlorn child sits in the distance.

As we take in these details, we realize with a shock that these scenes have travelled a long distance to inhabit this frame: the Madonna and child come from a Presentation in the Temple; the fallen man belongs in a pictorial account of the Deposition of Christ; and the abandoned child in the clearing recalls to mind da Vinci’s portrait of St Jerome in the wilderness. The structure of the diptych is precarious, with the scenes just discussed balancing on another stratum of depiction, showing ordinary citizens passing in the street. This precariousness is deliberate; the painting mirrors the structure of Matthias Grünewald’s paintings for the Isenheim altarpiece (1512-1516), with its main panel and wings balanced on a predella or threshold panel. These images, transiting between mediaeval Christian iconography and present-day Bombay/ Thane, build into a parable about hope lost, redemption deferred, and people driven into a spiritual no man’s land.

A reproduction of the Isenheim altarpiece, its sculpted elements by Niclaus of Haguenau and its paintings by Grünewald, is inserted into the exhibition, as a point of reference and comparison that provokes us into re-reading Patwardhan’s painting.

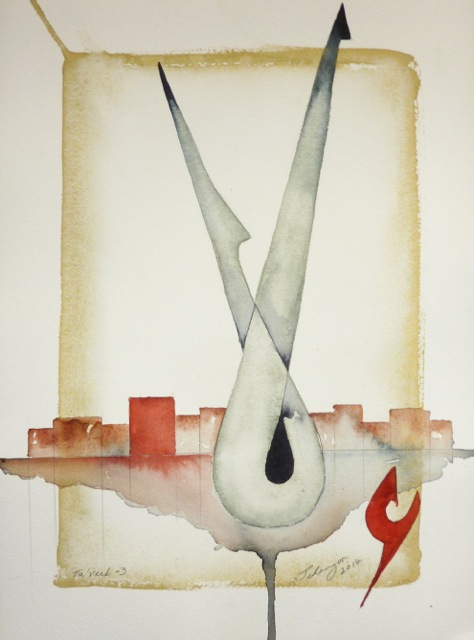

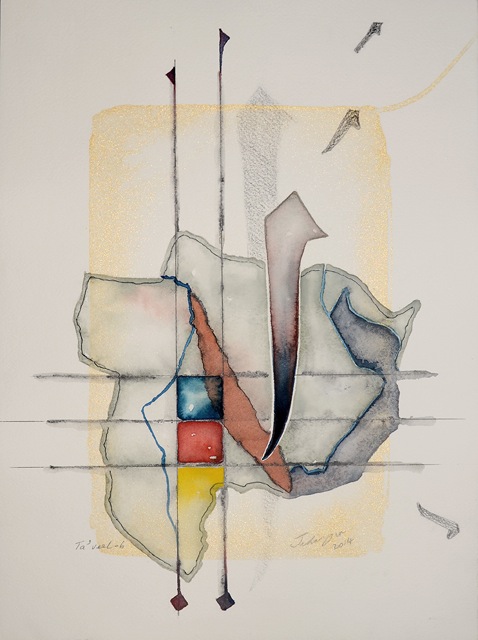

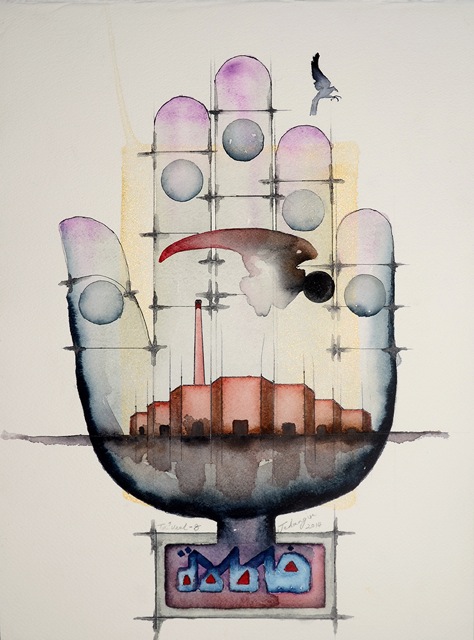

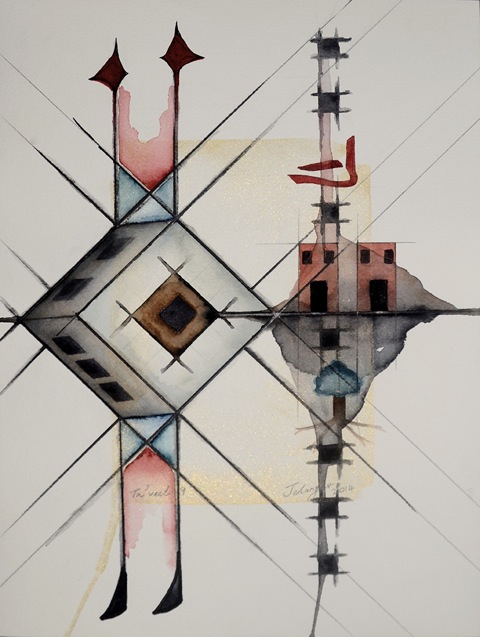

Jehangir Jani acts as a mimar of syllables, an architect working in the ruins of calligraphy, to re-shape the primal coherence of language through approximations, conjectures, calligrams and mosaics. In his 2014 series of nine watercolours, ‘Ta’veel (Postcard Series)’, he works with episodic, fragmentary elements of Arabic calligraphy, as well as with floating, half-disguised symbols such as the minar or minaret, panja or hand-print and ka’aba or holy cube, which he extracts from the deep archive of Shi’a religious experience. These works suggest the liminality, the threshold condition that he occupies as a secularized artist who, nevertheless, derives psychic and cultural energy from his family and community traditions. His threshold is the location between what he calls the ‘architecture of belief’ on one side and the grammar of universalizing abstraction on the other. This location is rendered more complex by the private, almost secret meanings that Jani encrypts into these works: the body threatened by varied scourges of the epoch such as the HIV syndrome, sectarian strife and the possibility of nuclear meltdown. Jani’s morphed forms propose an alphabet of thingness and uncertainty, wound and healing, belief and doubt, which invites us to decipher it.

*

Afterlife

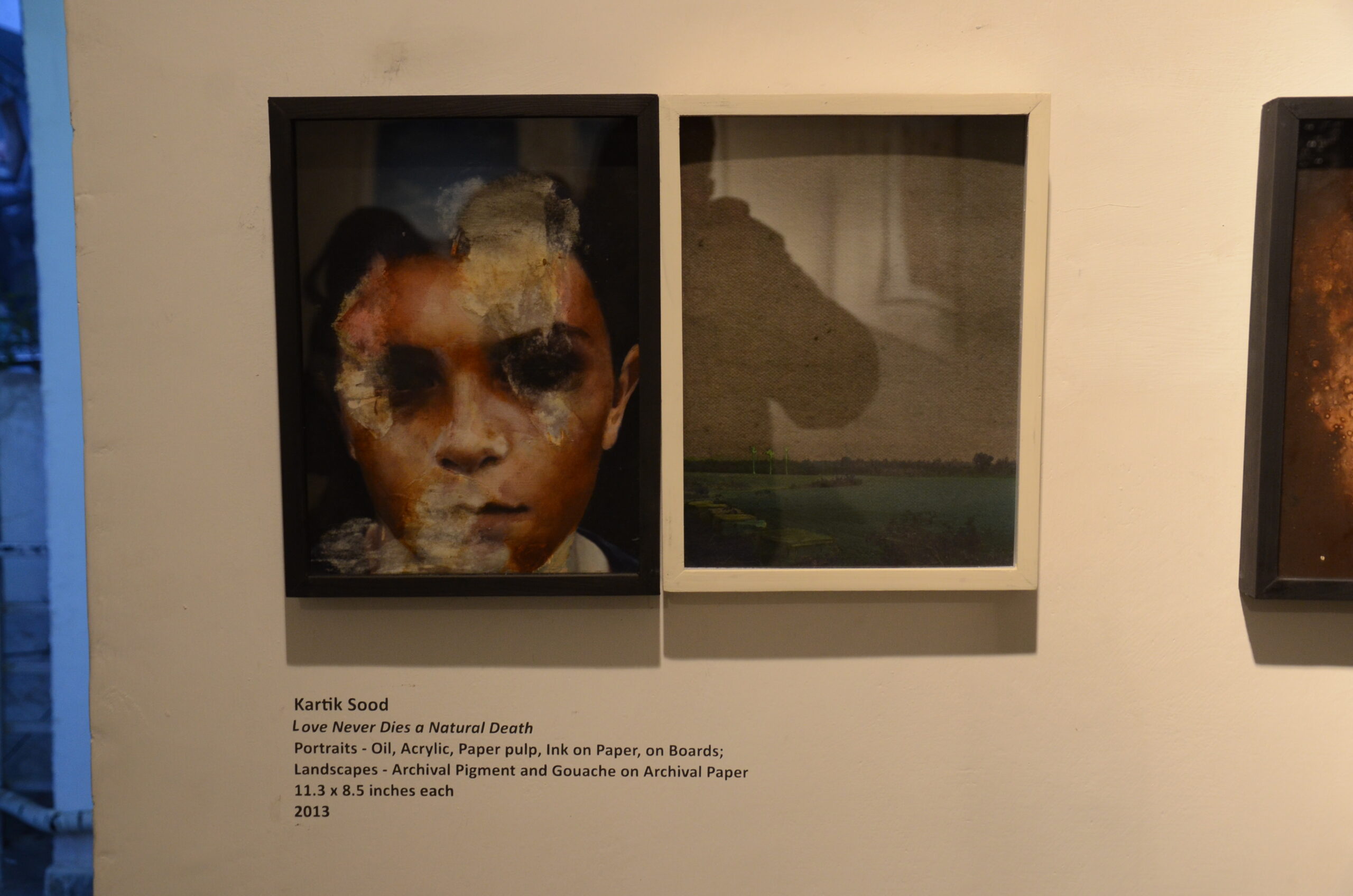

The afterlife is a vital element of the sacred: it indicates those persisting extended temporalities by which forms, images and indeed lives might continue to influence contexts and experiences far removed from those in which they originally flourished. A tradition of philosophical inquiry, for instance, might migrate from the circles of debate in which it arose, and find habitation on alien shores. The presence of a saint-poet may continue after her physical extinction, in the form of a circulating corpus of poems carried into the future by the voices of disciples and votaries, so that the presence becomes the voice, relayed, echoing, memorized, found again in translation (for instance, Prajakta Palav’s workshop with village children). The hope of the afterlife also, and perhaps paradoxically, animates forms like funerary art, whether the Pharaonic tombs or the Faiyum portraits, the afterlife is that fascinating awareness of the strength, beauty and energy of those who are no longer living, encountered through trace images and memorial gestures (Kartik Sood’s paintings, for instance, are born of an enchantment that comprises, in equal proportions, magic and vulnerability).

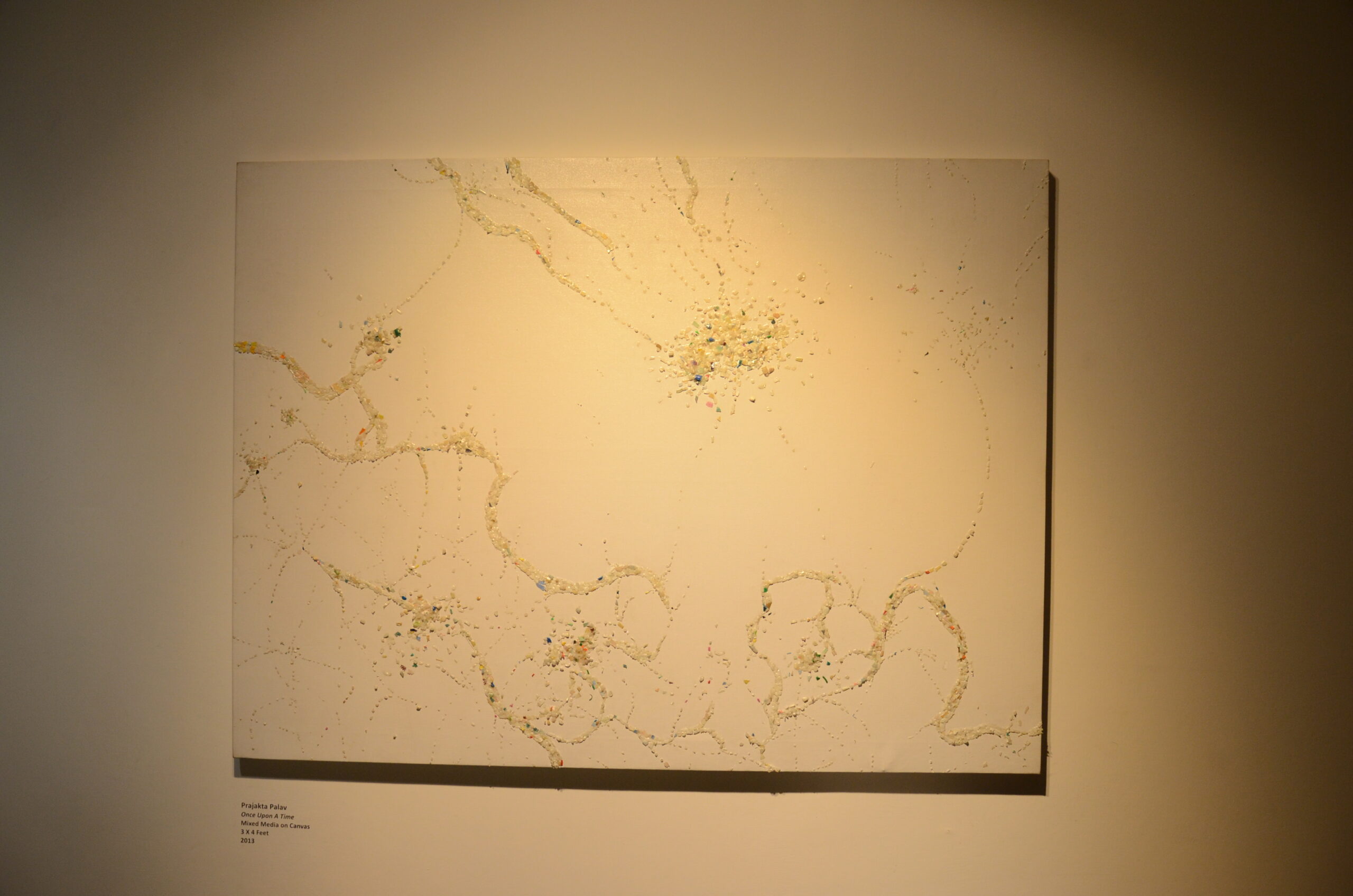

In framing Prajakta Palav’s work, I have invoked the cosmic tropes of visphota and pralaya, the explosion and the deluge, that underlie her awareness of a metropolis exploding with uncontainable multitudes, teeming with wastes that can no longer simply be returned to the earth. For ‘Sacred/ Scared’, I have chosen to present the residues of an ongoing project on which Palav is engaged: a workshop that she holds far away from the art world and outside the glare of public attention. She brings together schoolchildren in her native village, Bilwas, in Maharashtra’s coastal Sindhudurg district, to read and interpret the ovis or poems of a modern woman saint-poet, Bahinabai Chaudhari (1880-1951). Bahinabai’s poems, which she composed and sang in a dialect of Marathi, delighted in the imagery of home and nature, and imparted perennial folk wisdom to her listeners.

This quiet intervention in the lives of people who are marginalized by reason of social location and language may be viewed as an additive social project, all the more admirable because it is not funded by a grant-making body or undertaken with a view to adding to the artist’s resume. Instead, it embodies a complete departure from the painterly practice with which Palav is identified. Her interactions with the schoolchildren crystallize around Bahinabai’s poems, which she shares with them, eliciting their responses through the drawn and painted image.

In her notebook, Palav’s spontaneous translations of Bahinabai’s ovis from Marathi come to life. Amidst scribbles and scratches reflecting the activities of the workshop of the mind, word fragments emerge: “the unlearning, killing of the self”, “the coming and going (travelling) of spirit doesn’t end, when it takes a halt we call it living”. In the paintings that the children have made, a tree grows into the roof of the sky, and a field is lush with crops that look like green rain: looking at these images, you know you have come to a place where the boundaries are marked only by the wind.

The act of reading the ovis to the village schoolchildren has inspired Palav to make a meditative painting for this show. The mixed media work ‘Once upon a time’ may look like the detritus brought in by the sea. In a way it is mediated waste: Palav has used plastic scrap, broken it down and recycled it into her work.

Another kind of recycling is evident in Kartik Sood’s paintings which act like prayers for the dead: even as their bodies return to the elements, the memory of all that inspired them is embodied through lyrical evocation.

Strange and Sublime Addresses

The body is a costume for states of transformation, and sometimes, an artist, acting in shamanic mode, can tempt an unidentified totem creature or spirit animal to break the cover of civility mandated by social life. Or the artist, drawing on the expertise of the astronomer, the genetic biologist or the surveyor, might simulate an out-of-body experience. As elegist for a planet ruined by the species that has been its chief beneficiary, the artist can explore violated landscapes, bear witness to the industrial degradation of the earth and its resources. In such avatars does the Sublime – the ecological Sublime, the post-industrial Sublime – manifest itself. The Sublime transforms the viewing subject in the act of viewing, by exceeding the limits of the viewer’s customary optic, by breaking peremptorily with the viewer’s assumptions of normality, and by exposing the viewer to heightened conditions of strangeness, disorientation and terror.

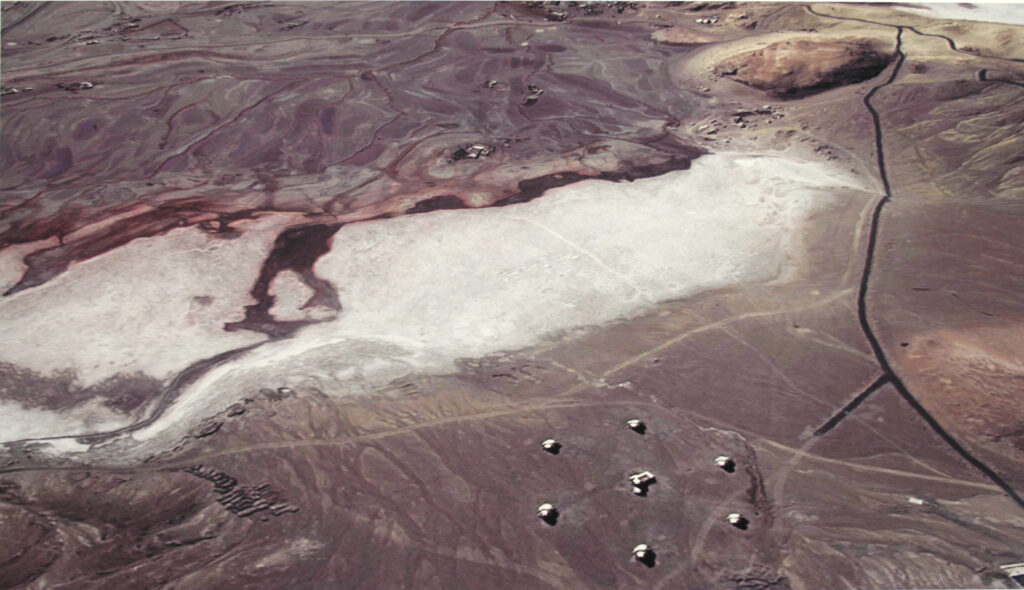

The shaman is Sahej Rahal’s exemplar; he focuses his attention on the point where form emerges from the ruins of iconography and is animated by a yet-unclassified pneuma. Inspired by astronomy and the aesthetic of satellite photography, Rohini Devasher invokes what Walter Benjamin described as the aura, the simultaneity of intimacy and distance, through her mythic, abstract topographies. Gigi Scaria dedicates himself to the earth’s last uninhabited expanses, where the human being can only be a survivor, a recipient of visions into the vastness yet also the fragility of the universe. The pilgrimage towards the Sublime is punctuated by markers of encounter: an electric pole held down by gravity just as it seems poised for ascension; a fallen pylon, like a broken cross; an archetypal circular track engraved into the earth, apparently made by a cosmic event or marking a primeval ritual, but actually the tracks left behind by trucks carrying the earth’s resources away to the factories.

This exhibition proposes that the sacred is not a pre-ordained and pre-shaped entity. It is an auratic, liminal condition, a tantalizing horizon: a place in which you find yourself without having looked for it.

Arriving there, we might say with Adrienne Rich, from ‘Midnight Salvage’, 1996:

‘find us in crazed niches sleeping like foxes we wanters we unwanted we wanted for the crime of being ourselves’

*