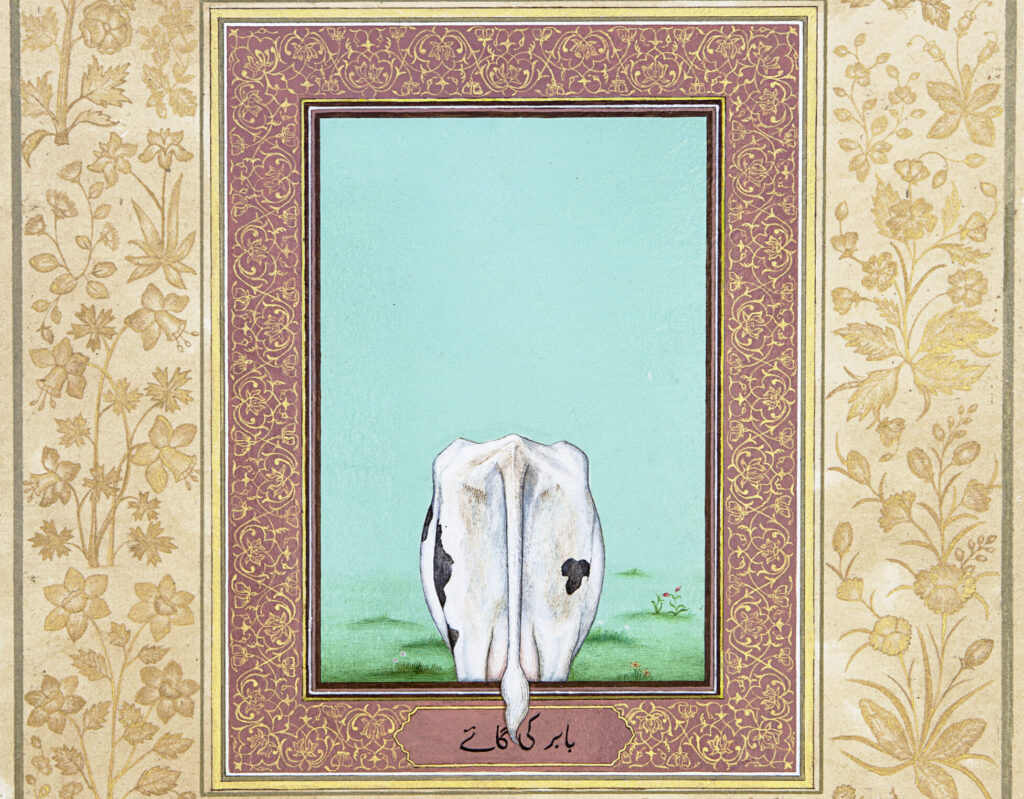

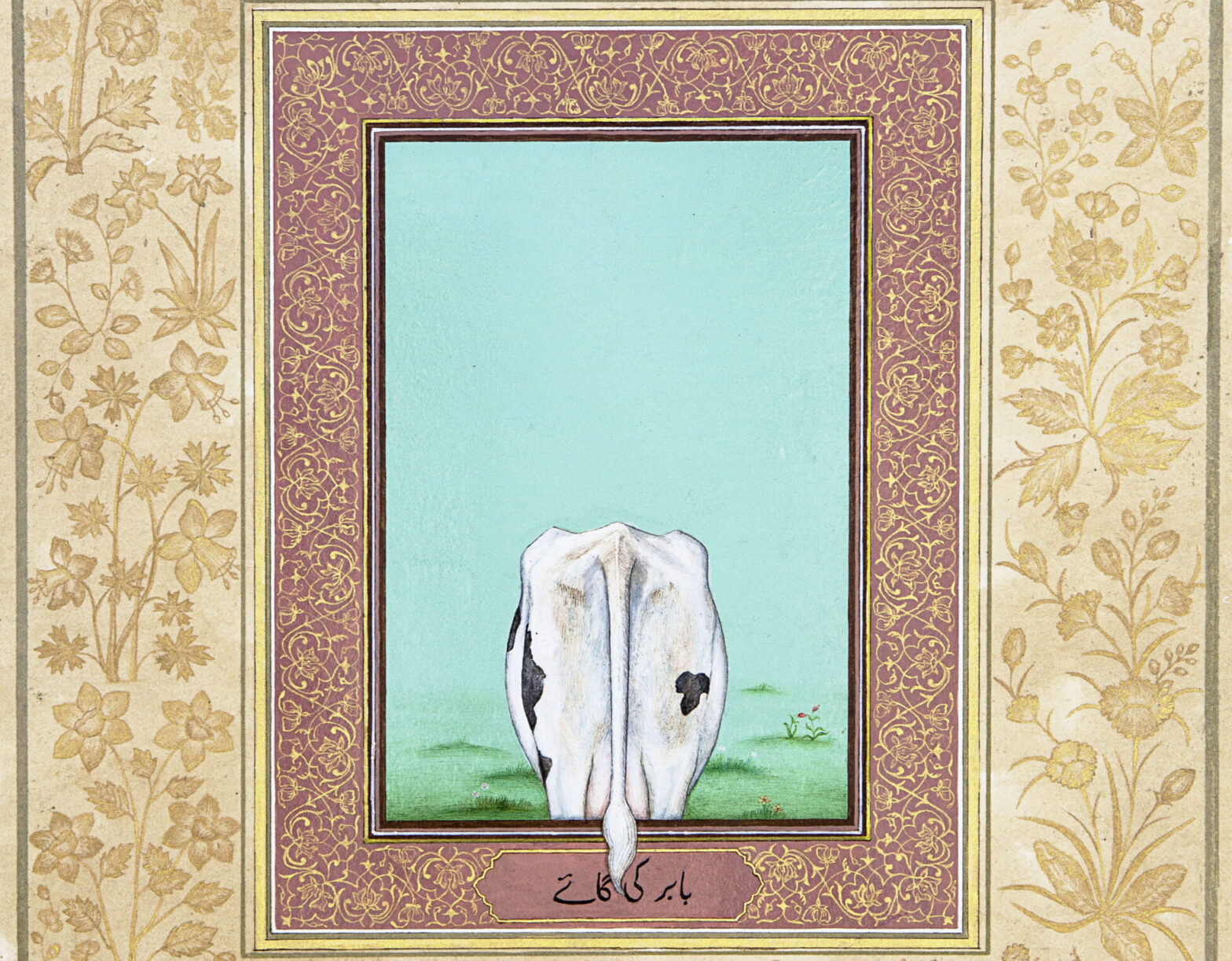

Babur Ki Gai

GROUP SHOW

Oct 25, 2018 - Dec 1, 2018

- SELECTED WORKS

- CURATORIAL NOTE

- PRESS RELEASE

- DOWNLOAD CATALOGUE

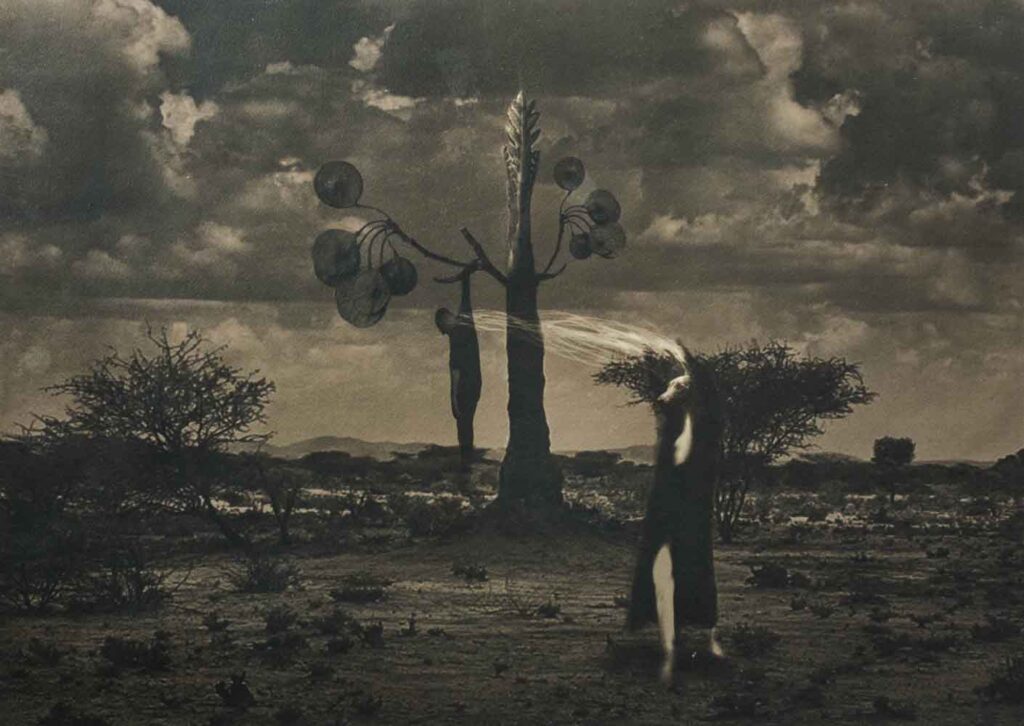

‘Babur ki Gai’ examines the oxymoron of ‘contemporary history’ through the phenomenon of mythopoesis commonly understood as the power of myths to engender or modulate reality. The concept of the ‘contemporary’ as the fleeting ‘nowness’ is at odds with history taken to mean the documented past. Like Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle, the instant the duration of the contemporary is registered, it seizes to be of the present and passes into the domain of the past. On the other hand, mythical thinking appears to operate from the vanishing point of an unspecified past, if not the pre-historic, from where it continues to guide the present. Its hold and influence is partly due to the patina of seemingly incontrovertible timelessness and veracity acquired through the repeated practice of collective belief over an extended period of time. Whilst the hauntology or the point of origination of myths is subject to uncertainty, their teleology remains firmly rooted in the present such that old myths are periodically revived and refitted to the demands of the contemporary. One way to create contemporary mythologies then is through speculation, a prognosis of the moment that is to unfold in the near future or is the projected outcome of a present continuous. An alternative way to go about the task would be through science-fictional worldbuilding or hyperstitional strategising whereby feedback loops are established between temporalities in order to reverse engineer the present through the vision-blocks of desired futures, not unlike the plot of the Terminator film series where certain agents from the future retroactively compete to p/reprogramme the present so as to secure a particular outcome in the future. By localising the point of origination of the myth in the conditional future, the fleeting ‘nowness’ or topicality of contemporary mythologies can be conserved. This way the present can be leavened up against gathering stasis through the clandestine infiltration of its matrix by alien codes that in time can bloom into alternative futurities.

CURATORIAL NOTE

This exhibition examines the oxymoron of ‘contemporary history’ through the phenomenon of mythopoesis commonly understood as the power of myths to engender or modulate reality. The concept of the ‘contemporary’ as the fleeting ‘nowness’ is at odds with history taken to mean the documented past. Like Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle, the instant the duration of the contemporary is registered, it seizes to be of the present and passes into the domain of the past. On the other hand, mythical thinking appears to operate from the vanishing point of an unspecified past, if not the pre-historic, from where it continues to guide the present. Its hold and influence is partly due to the patina of seemingly incontrovertible timelessness and veracity acquired through the repeated practice of collective belief over an extended period of time. Whilst the hauntology or the point of origination of myths is subject to uncertainty, their teleology remains firmly rooted in the present such that old myths are periodically revived and refitted to the demands of the contemporary. One way to create contemporary mythologies then is through speculation, a prognosis of the moment that is to unfold in the near future or is the projected outcome of a present continuous. An alternative way to go about the task would be through science-fictional worldbuilding or hyperstitional strategising whereby feedback loops are established between temporalities in order to reverse engineer the present through the vision-blocks of desired futures, not unlike the plot of the Terminator film series where certain agents from the future retroactively compete to p/reprogramme the present so as to secure a particular outcome in the future. By localising the point of origination of the myth in the conditional future, the fleeting ‘nowness’ or topicality of contemporary mythologies can be conserved. This way the present can be leavened up against gathering stasis through the clandestine infiltration of its matrix by alien codes that in time can bloom into alternative futurities. This exhibition takes the following questions as its point of departure: Why are artistic practitioners increasingly turning to fabulations and futurisims in the current times? What kind of constructions are coming up around myths in art practices and how are these fabulations enabling the revision of dominant realities/ fictions? What are the advantages to be gained from contemporary myths/ magical thinking as opposed to the ‘scientific’ modes of history/ rational thought?

Claude Lévi-Strauss in his key contribution to structuralist anthropology, The Savage Mind (1962) remarked,

“Magical thought is not to be regarded as a beginning, a rudiment, a sketch, a part of a whole which has not yet materialised. It forms a well-articulated system… It is therefore better, instead of contrasting magic and science, to compare them as two parallel modes of acquiring knowledge… Both science and magic… require the same sort of mental operations and they differ not so much in kind as in the different types of phenomena to which they are applied.”

In this scheme, magical thought appears to be not so much a function of man’s “mythmaking faculty, turning its back on reality” but a primordial intuitive technique of organising the sensible world around according to its own set of internally coherent principles which may vary, at times significantly, from those employed by science, according to the difference in values emphasised and objectives sought, but are nevertheless equally serviceable within the limits of the world(s) or contexts where they are deployed and are well capable of independently reaching “brilliant unforeseen results on the intellectual plane.” Thus, the primary distinction between myths and science that the exhibition takes as its premise would appear to be the different subjects of attention that each of them employ as well as the purposes they are applied to. The underlying assumption here is that myths, and significantly those repurposed by artists for our current times, are able to effectuate a shift in attention/perspective/priority with regards to the integrated reality, potentially calling it into revision. Armed with these tropes of ‘fictioning’ the artists are able to beg our attention, through methods that are singular, to salient issues and ways of being in the world that are too easily dismissed as inconsequential, non-pressing or untenable.

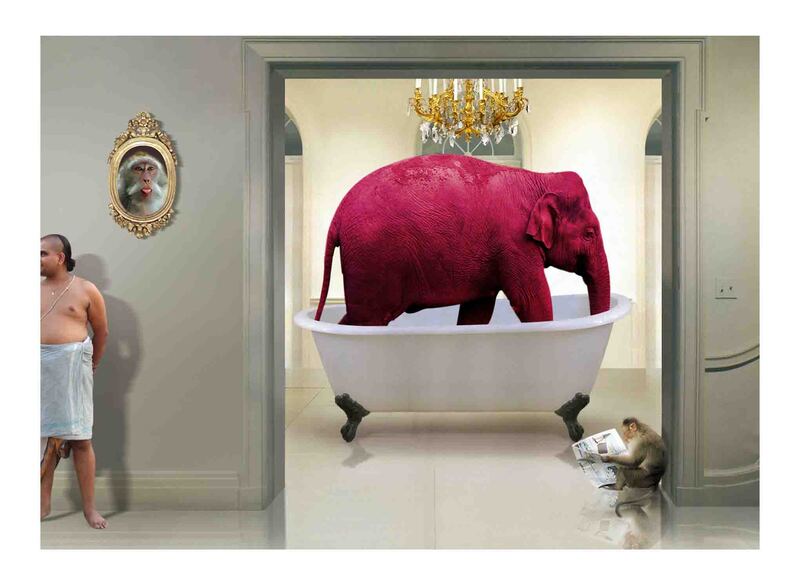

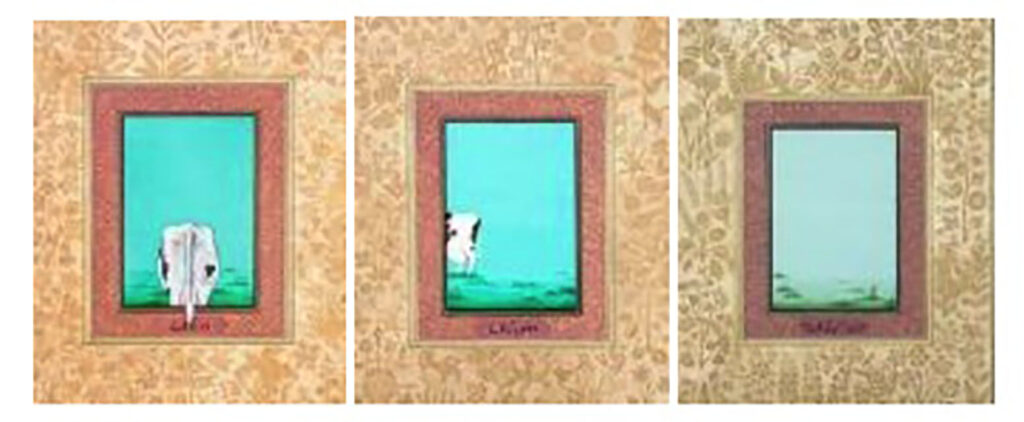

The title, ‘Babur ki Gai’ refers to a key artwork in the show by Priyanka D’Souza, who claims to have recovered the lost pages from the Baburnama folio. The authenticity of these pages as well as their accidental invocation by Madan Lal Saini, the BJP chief in Rajasthan in support of the agenda to ban cow slaughter is however contested, as the researchers suggest that the mention of cow slaughter happens not in the Baburnama but in Babur’s ‘wasaya’ or will, itself proven to be a 17th century forgery. As such, the title ‘Babur ki Gai’ encapsulates the casual throwing of certain shared beliefs and myths as if they were actual historical facts, in order to achieve political ends, and the general discrediting of truth in a world that increasingly traffics in brutality, anti-intellectualism, misinformation, doctored reports and fake news. Conversely, it speaks to a particular a priori logic characteristic of mythical thinking that constitutes the conditions of its own existence, to the general power of myths to render the reality around them, and the ways in which artists are able to tap into this arcane para-historical powerhouse to pervade the reality with corrective fictions and vitalising utopias. In this way, ‘Babur ki Gai’ also hints at the mythopoetic function whereby the artists are able to contest certain political ideologies or dominant social norms with unconventional belief systems and alternative visions of the world. In the final instance, and perhaps as a self-critique, it also acknowledges the slightly alarming collusion between future-oriented media/ technotopias and capitalism, termed by the late British cultural theorist Mark Fisher as ‘science fiction capital’. This collusion appears to be cheating us of our future conditional by infiltrating the world-as-we-know-it with certain insidious signals, specific visions of the future favourable to the current economic systems, that are deviously programming and accelerating our present towards those cybernetic futurities, calling them into being. Needless to say, the mythopoetic power vested in science fiction (and fiction in general) has both its uses and abuses and merits exercising with great care and responsibility.

The artists in the exhibition employ ‘fictioning’ as a time-travelling device and rely on the inherent power of myths to shape or alter reality. This mythopoetic power is exercised to various degrees and effects across, what can be broadly identified as, five distinguishable fields: socio-political, religious/metaphysical, corporeal/feminist, utopian, and subjective/ identitarian.

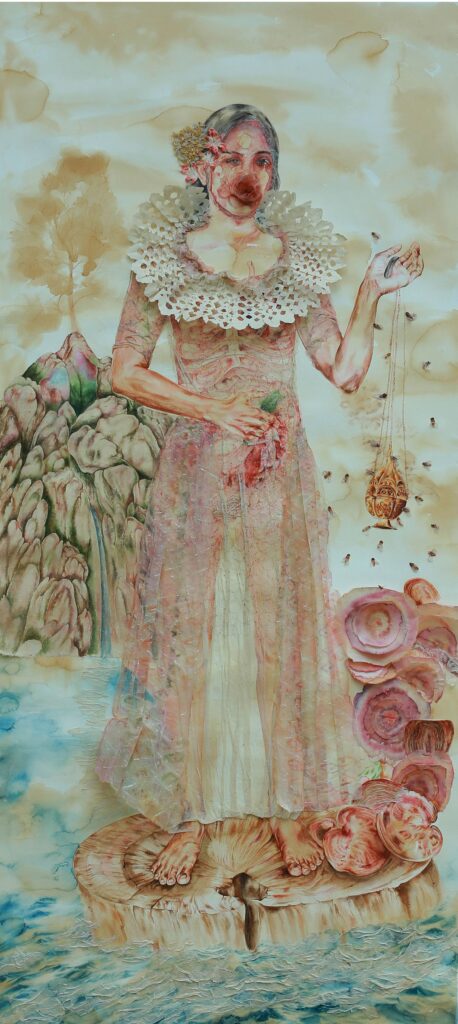

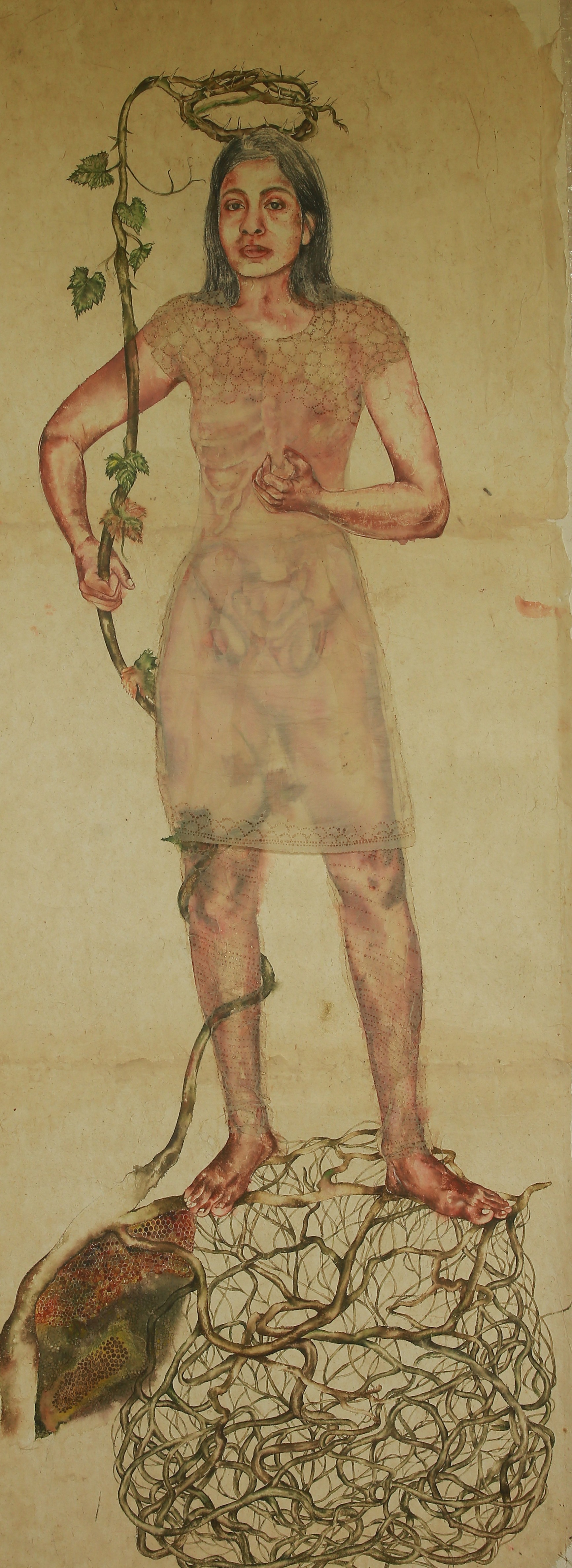

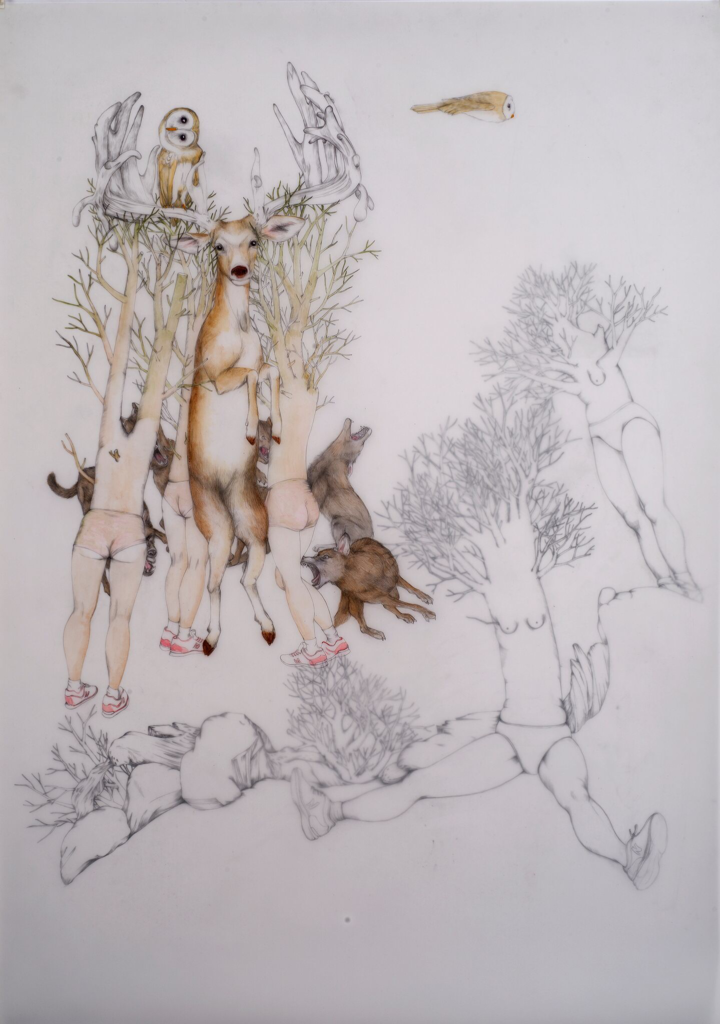

Admittedly, some of the artworks do not neatly inhabit the categories under which they are featured, spilling over into others. For instance, it is possible to read Anupama Alias’s works under both the heads of religious/ metaphysical and corporeal/feminist.

Yogesh Ramkrishna’s present body of work is stitched together from the material gathered during a research trip last year to a small village in Maharashtra by the name of Dhotre. Most of his conversations with the villagers were centered on the enigma of a ruined house that was burned down by the villagers some years ago with a lone child survivor who was never again to be seen. Over the years, several mollifying rituals and rites have mushroomed around the charred remains of the building and the villagers speak animatedly about the lives of those that once inhabited the house and have several different accounts and telling of the events leading up to the carnage. During the research period spanning several months the artist was able to put together a rough sketch of this haunting by collaging stories, recollections, hearsay, superstitions and popular beliefs, supplementing the missing fragments with other myths prevalent in the region as well as a fair bit of creative conjecturing. Through these drawings and self-composed poems (translated from Marathi) the artist is able to reanimate the memory of this house and the events that led to its tragic razing, believing his compiled version to be true, if yet unproven. In this way, Ramkrishna validates the mythos surrounding the house, giving us a peak into some magical modes of thinking and reminding us of the enduring power of myths in large portions of the country.

Ketaki Sarpotdar’s satirical etchings fuse Animal Farm or Panchatantra type of characters and scenarios with an aesthetic appropriated from present-day media and news channels that thrive off cheap sensationalism and “breaking news”. In the etchings on display slaughter animals like goats and pigs are branding together for what appears to be the making of a revolutionary war against their old masters. Underground gatherings and sloganeering point to the impending violence/ restitution. The imagery is clearly intercepted from media channels that assume animal-folk as its intended audience and can either signify a mass turning of tables on human domination or the inevitable process of ‘othering’ and indiscriminatory violence that such ideologies so often degenerate into in the name of political mobilisation and effectiveness.

Similarly, Priyesh Trivedi’s iconic Adarsh Balak series subverts the imagery of state-sponsored idealism advocated through certain educational charts and propaganda posters popular in classrooms in the 1980s and 90s. Here the handbook representing the stereotype of an ideal student is utterly turned on its head, with pages depicting a post-capitalist scenario with children in uniform nonchalantly going about nihilistic activities such as smoking marijuana, drinking alcohol or poisoning the town’s water supply, in the face of approaching apocalypse.

With this series Kedar Dhondu seeks to unearth the histories associated with certain local shrines that have mysteriously survived the interregnal violence characterising cultural or political shifts in the Goan hinterland, starting with the influx of Portuguese colonisers in the 16th century. Whilst the masses struggled to negotiate the waves of religious and cultural persecutions, the divinities had to fight a parallel war for relevance and potency. It is this latter trajectory of divinities dislocated and emplaced, sometimes in utterly different, even ironic contexts such as museums, antique shops and private collections abroad, that the artist is interested in narrativising.

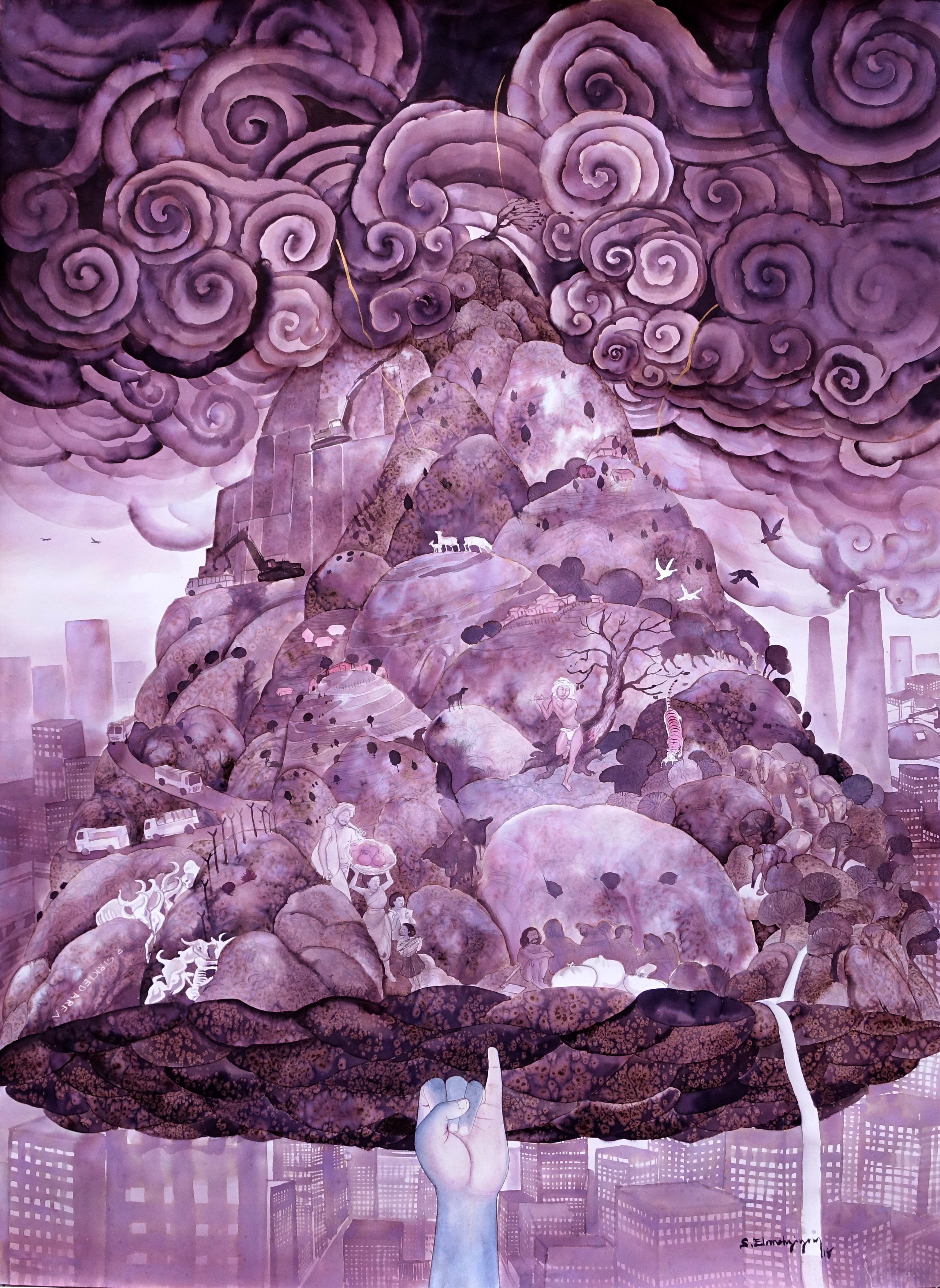

Extending the tradition of satirical illustrations that the Tamil artist Elancheziyan S. regularly contributes to various magazines and newspapers, the watercolour entitled Lifting Govardhanagiri on view here, crosshatches the imagery of Krishna lifting the Govardhan hill on his little finger to shelter the villagers and fauna from the destruction sent by the angry rain god, Indra, with the day-to-day struggles of certain tribal minorities and more-than-humans in modern India. The ruthless pace of industrialisation is clearly featured in the work as a threat and a burden to the pre-industrial mythical economy and the natural world. As such, the central hilly motif in the work can be viewed as an expression for miraculous hope that can halt this relentless destruction of life-as-we-know-it in its tracks.

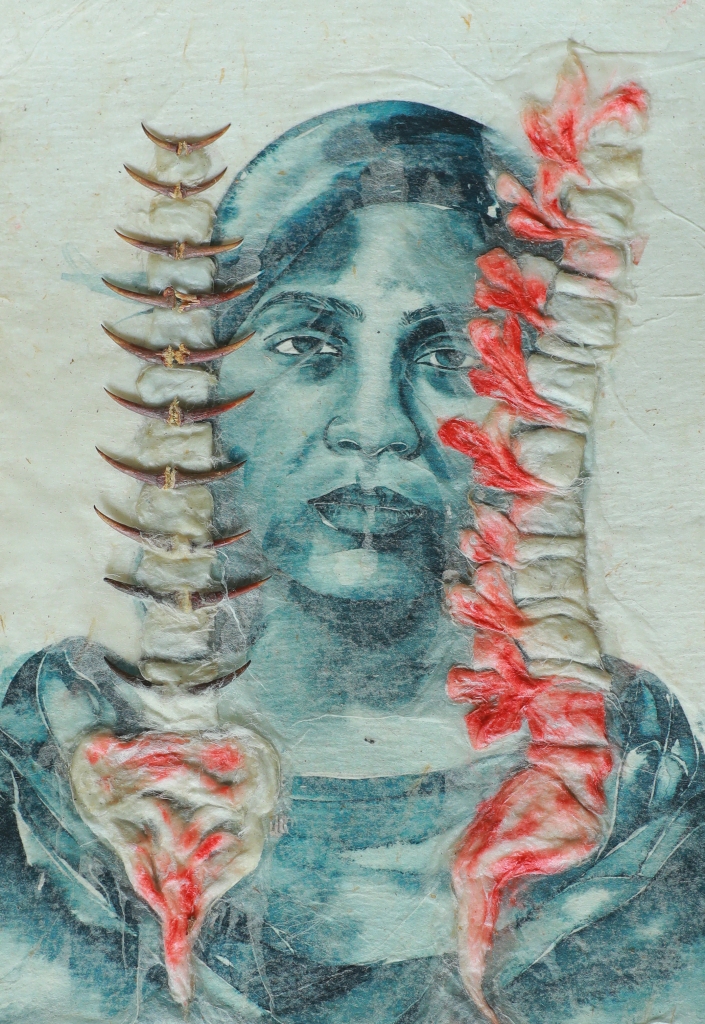

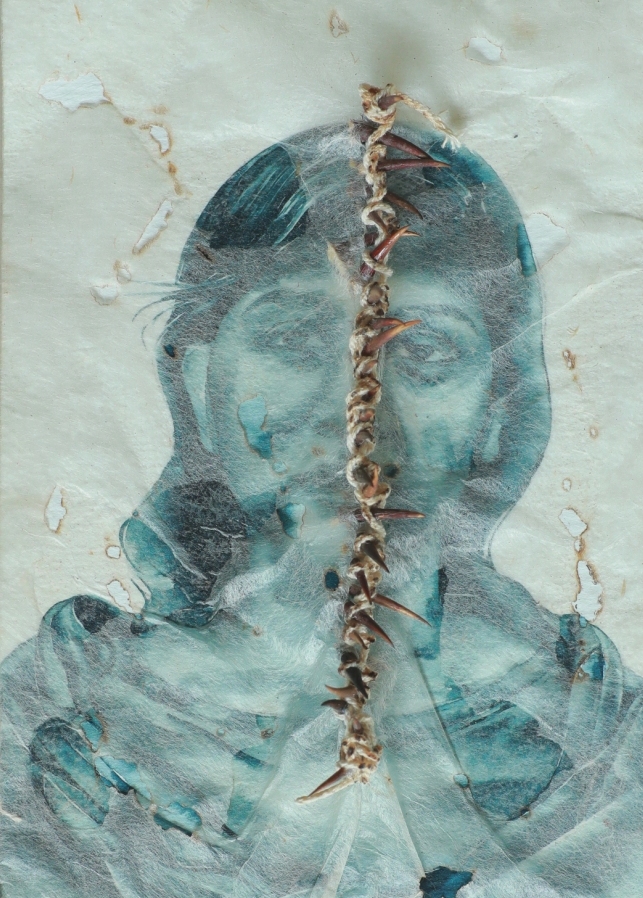

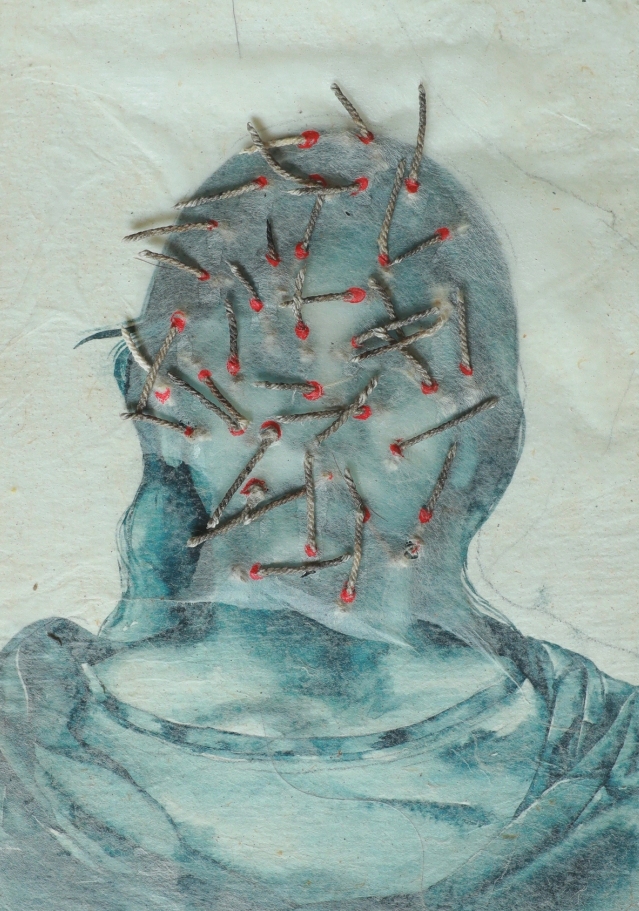

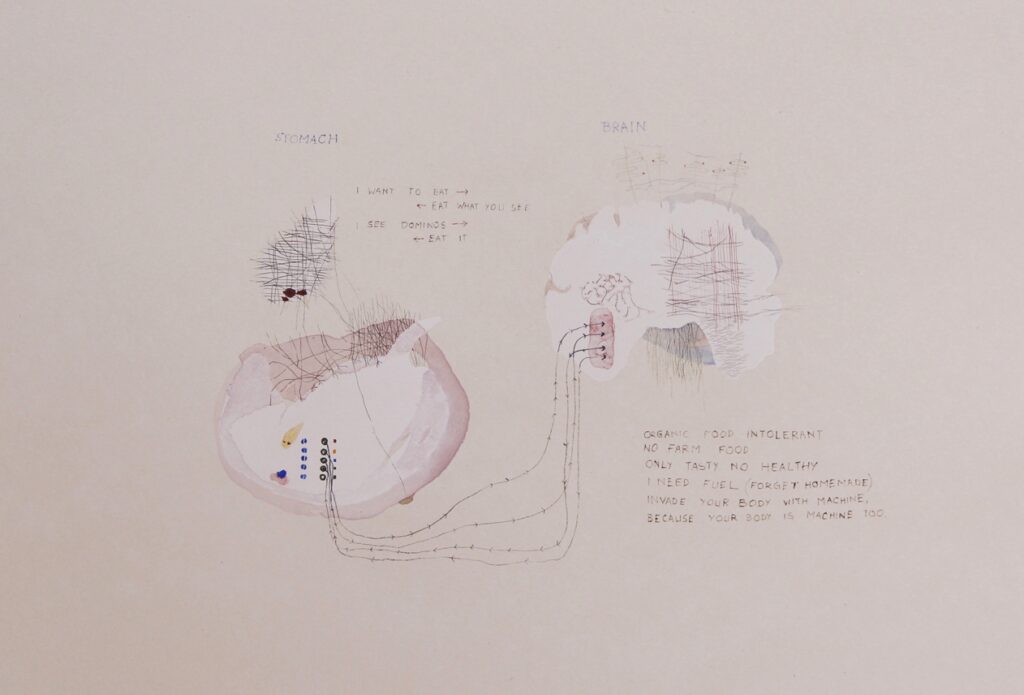

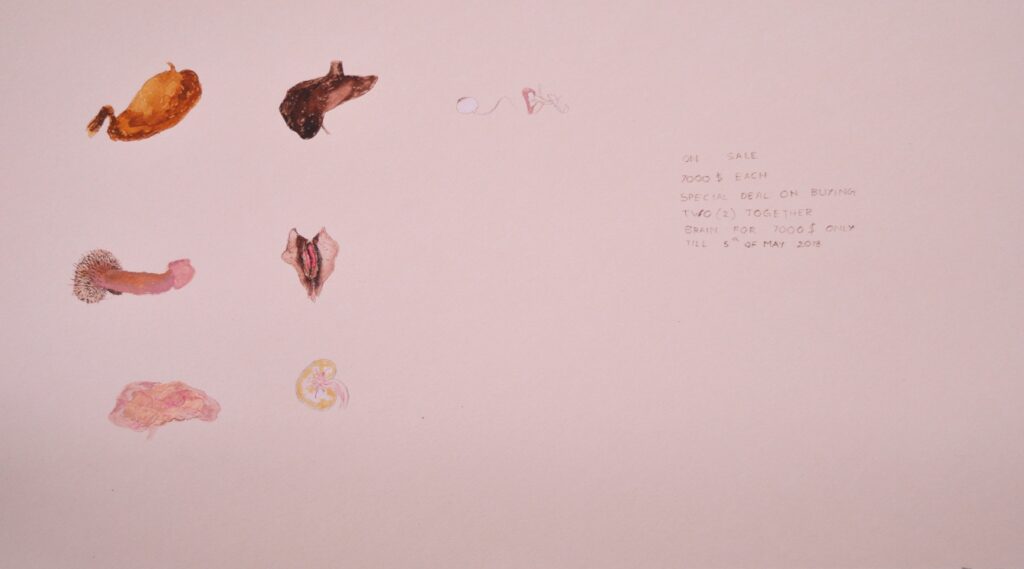

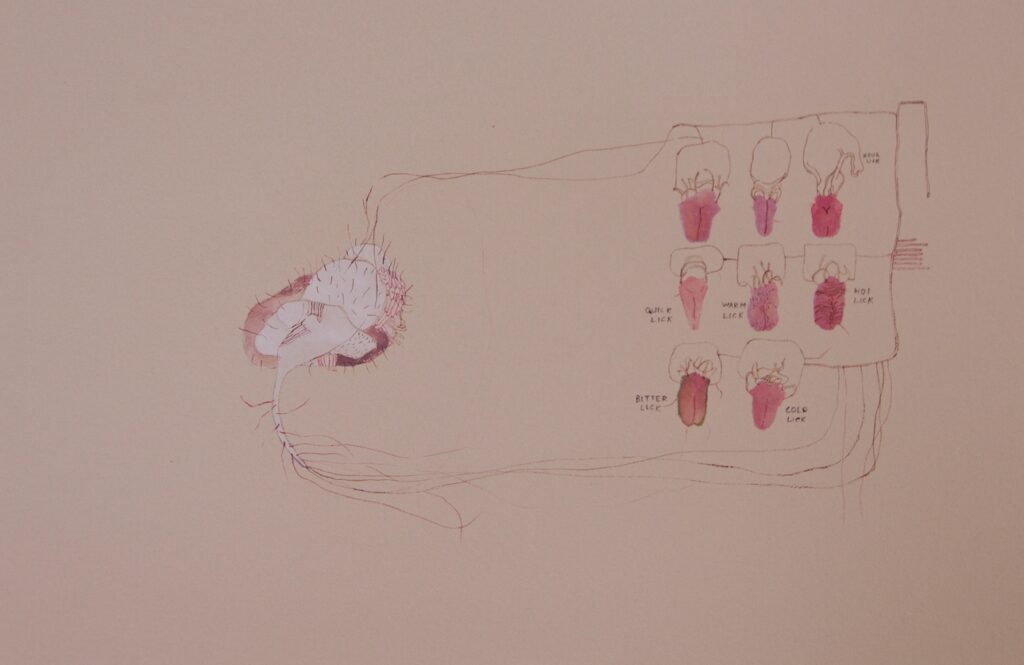

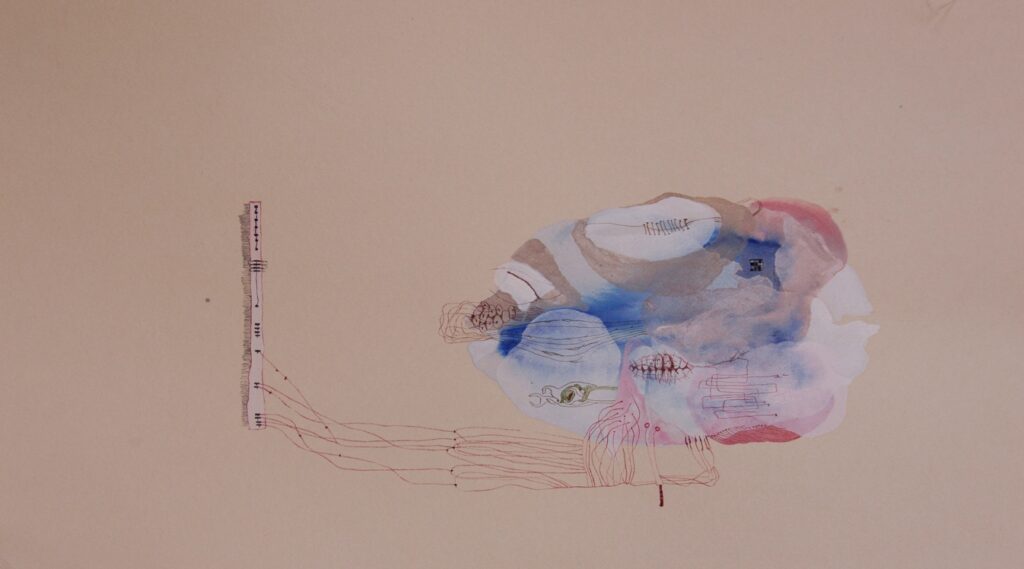

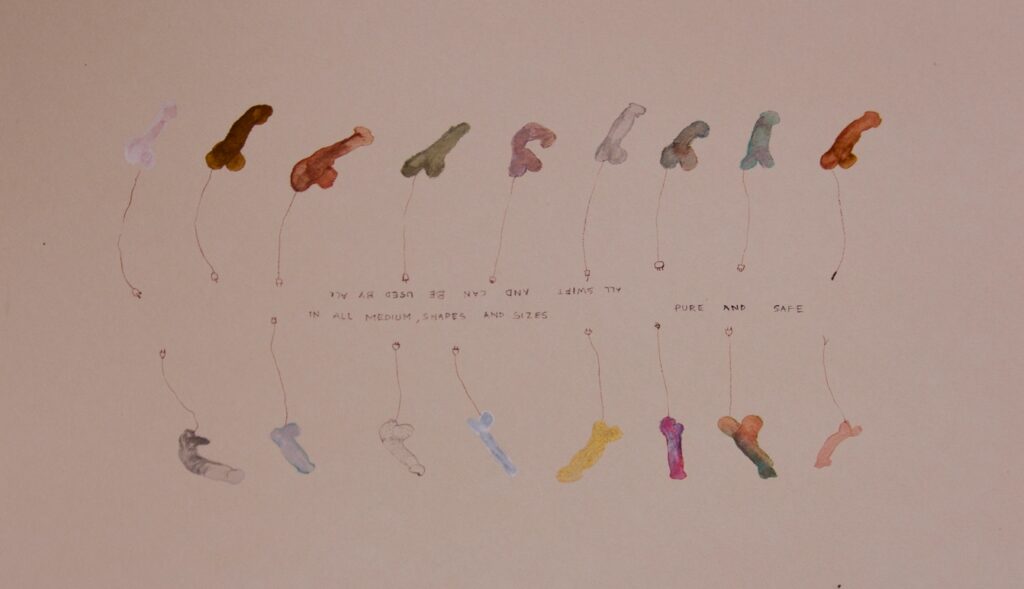

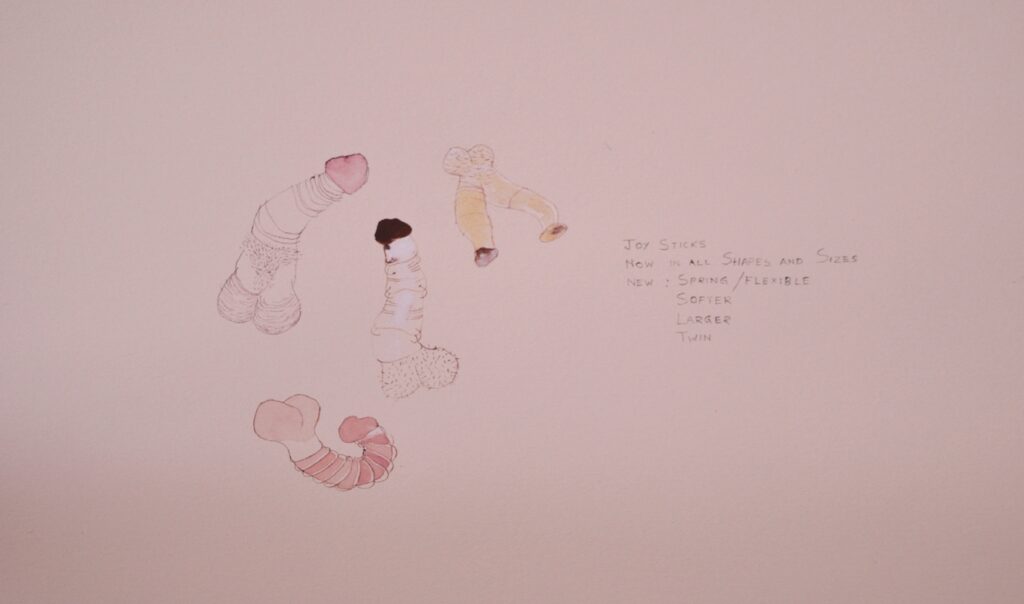

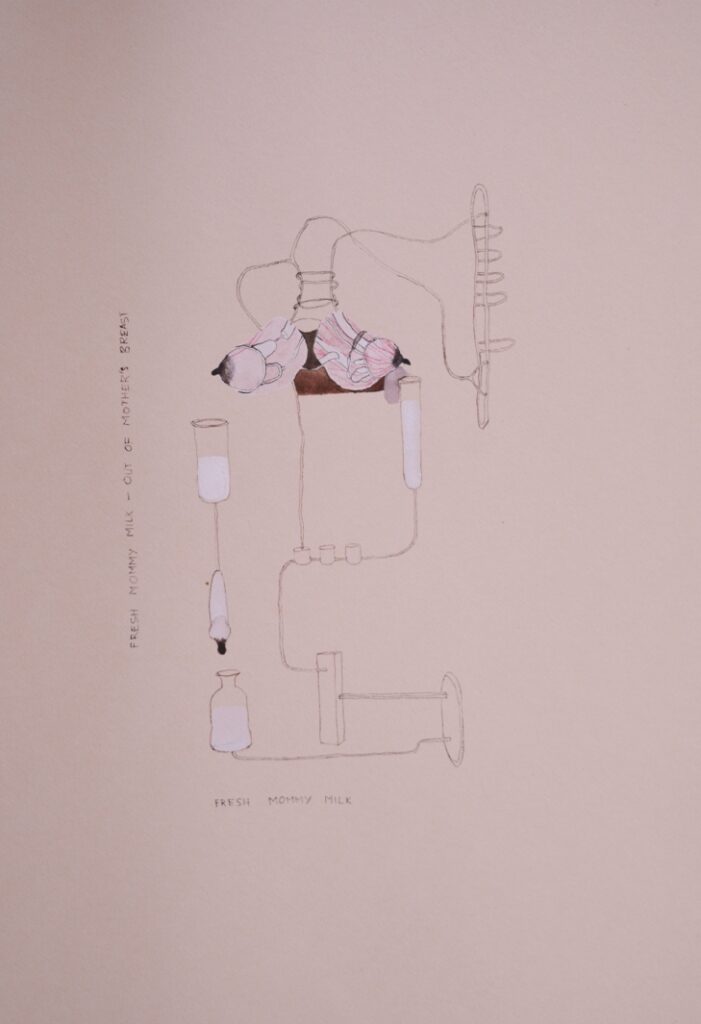

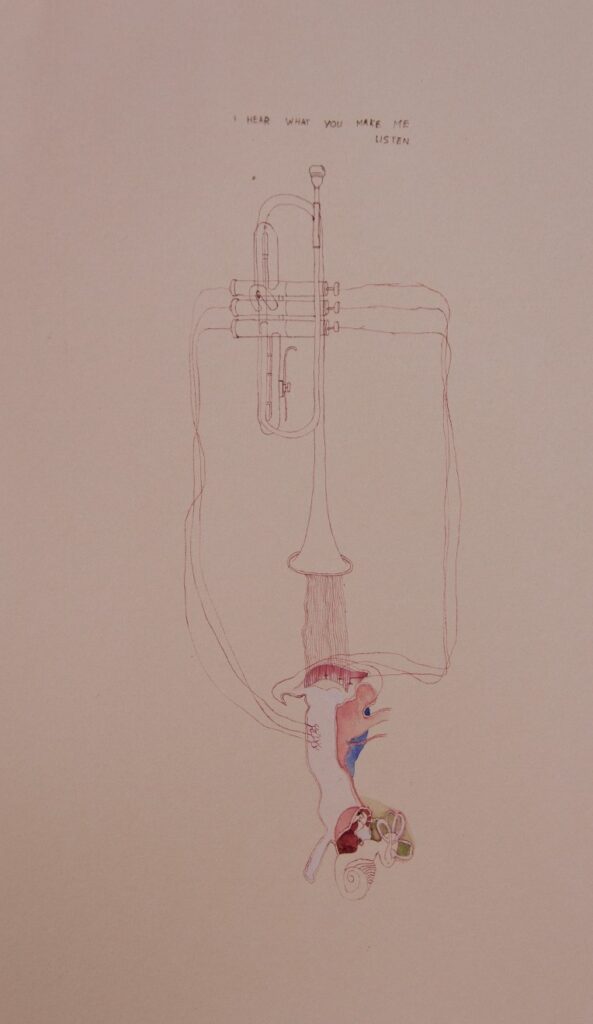

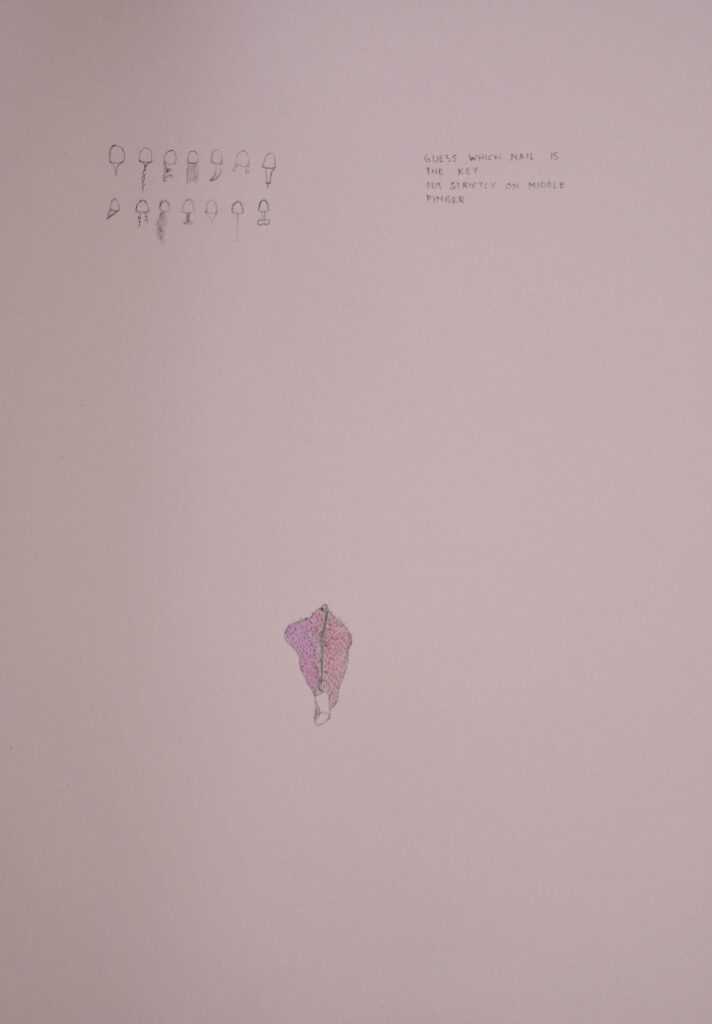

In the Dystopia series Pujashree Burman focuses the lens of her inquiry onto the terrain of the body, tearing into its mythological flesh layer by layer. Giving the lie to its mythical discreteness and naturalness, the artworks mimic the chemico-machinic complicity of the human body and its affected systematicness — the various rhythms, functions and habits that technology stamps on our bodies. The disjunction between the rate of technological advancement and that at which these changes are incorporated into the body, resolves into a somato-tenchnical glitch conveyed through the bare and recursive didactics in these works.

“You were there. I could hear you, but I only caught glimpses of you in the glass. Eventually I gave in and found myself staring at myself, reflected. Looking at myself looking back at me. Both of us trying to decipher the face that was in front of us. My eyes seeing me in mine and countless.” — An excerpt from Then She fell (an immersive theatre, based on the story of Alice in Wonderland).

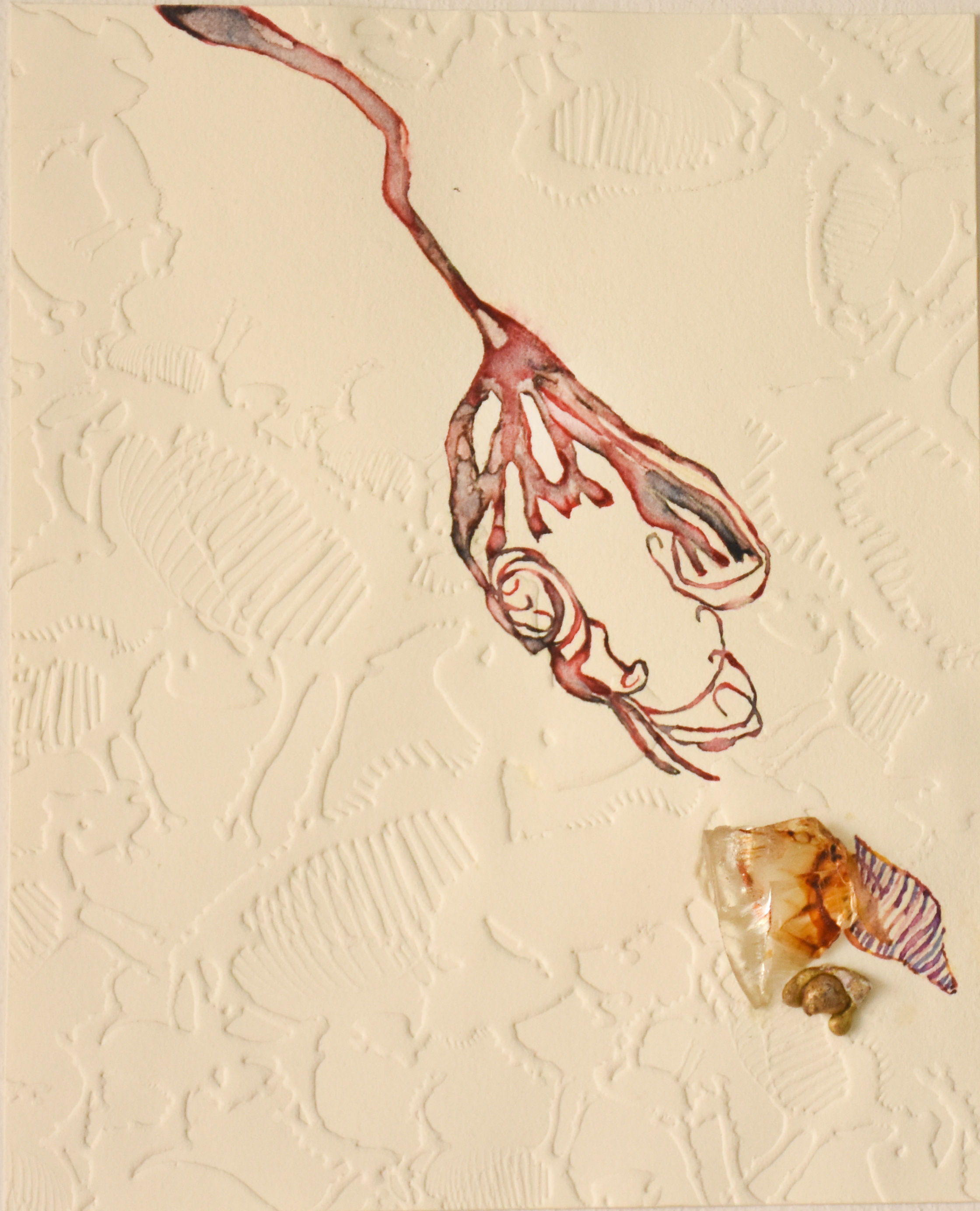

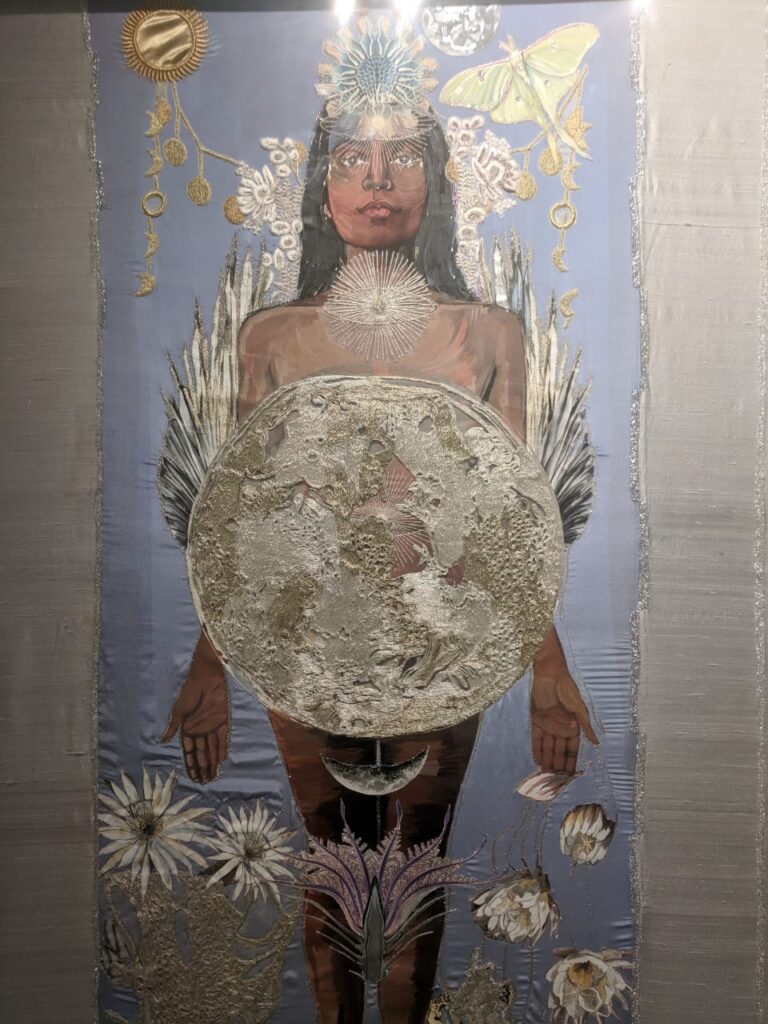

Anupama Alias reinterprets Christian and Hebrew iconography to voice her feminist concerns. The second chapter of Genesis relates the story of creation of Eve from Adam’s ribcage. Is this then the original blood and tissue debt writ into the sociological contract governing relationship between the sexes, that makes the womankind subordinate to man and constantly position herself to his advantage “that he may expose and relieve the thigh bones, the ribs, of his vanity, of his urgent desire to assert himself”? Alias’ works poses some of these questions by re-writing women into ecclesiastical spaces, roles and metaphysics that have traditionally excluded or relegated them.

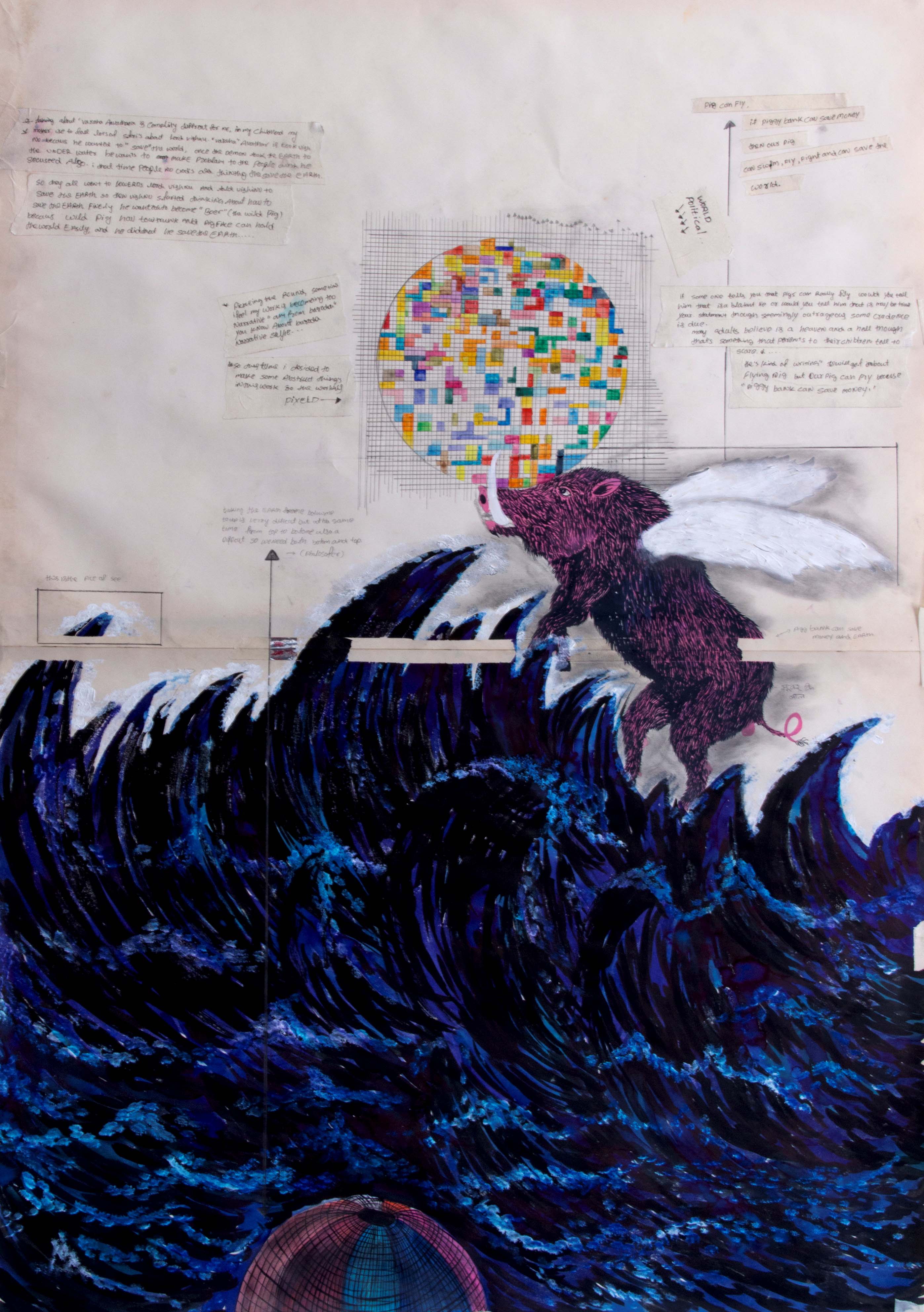

In his work Pig and Piggy Bank Shailesh BR conflates the Puranic legend of Vishnu as the Varaha avatar (wild boar) rescuing the earth from the depths of the ocean where it was sunk by the demon Hiranyaksha, and the modern day banking and economic systems that present themselves as the highpoint of our collective knowledge and civilizational enterprise, with their implied promise: money will save the world! Using his characteristically playful idiom to create a collage with the recurring porcine motif, the artist humorously reincarnates Vishnu, the god of preservation, in his final avatar of all-encompassing, homogenising, and numbing capitalism which, at least, in the immediate aftermath of the collapse of the last bastion of communism in the 90’s and with its golden promise of unprecedented deterritorialisation, had a certain appeal and purchase. Of course, that promise has since been proven to be at best a phony one and as such in this final avatar Vishnu appears not so much a force of preservation but one that tolls the death knell for the ‘anthropocene’.

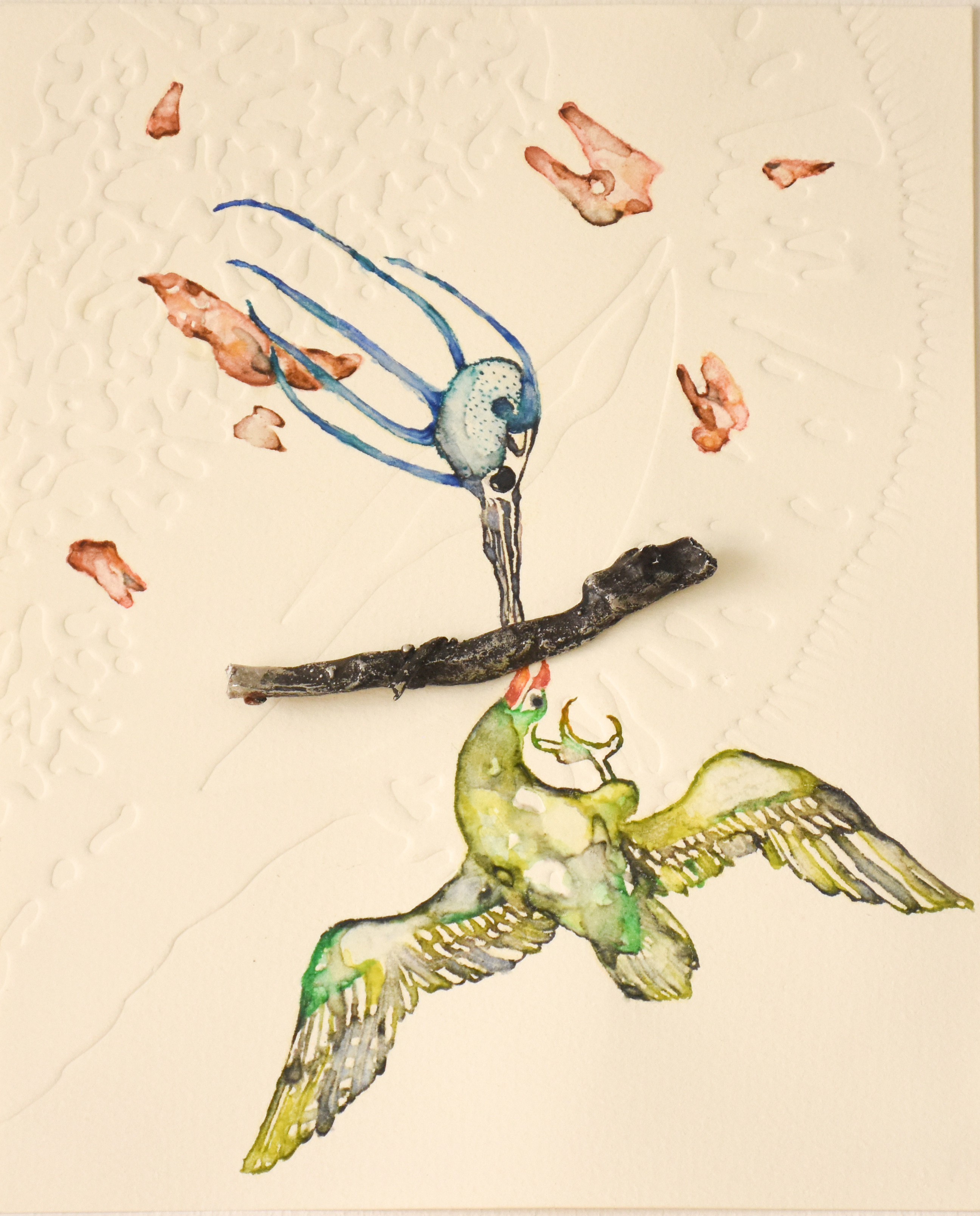

Radhika Agarwala’s new series of works, Cenozoic Trance is eerily reminiscent of an excavation site. What appear to be claws are suspended from the ceiling as if hung to be dried, or as if some inexplicable but possibly magical event had decapitated the body of the bird it belonged to, but had left its limbs behind for the viewer to ponder over and put together the pieces of an unsolvable puzzle. On the floor are shards of a crystal like substance and three miniaturized totemic structures. Fossilized inside these manmade crystals of extremely toxic polyepoxide is a microcosmic ecological system that reflects the post anthropocentric world we currently inhabit – bits of concrete, iron shavings, gravel, insects, parts of uprooted trees covered in earth oozing in its own goo but also in the chemicals of the resin. Mimicking shards of glass strewn across the floor, one could almost hear the ring of the crash of an object falling in the absence of an audience much like riven blocks of polar ice have melted without our knowledge for centuries. Agarwala’s works are at once artefacts of an event not yet occurred and of events that have gone undetected for decades; like an echo of a Maori song after the huias had become long extinct, these works are fossils that contain imagined traces of a story that is lost forever.

The hollowed-out terracotta sculptures of Manjunath Kamath pay homage to Vaishnavite myths and iconography.