Dissensus

GROUP SHOW

Jul 7, 2017 - Jul 16, 2017

- SELECTED WORKS

- CURATORIAL NOTE

- INVITE

- PRESS RELEASE

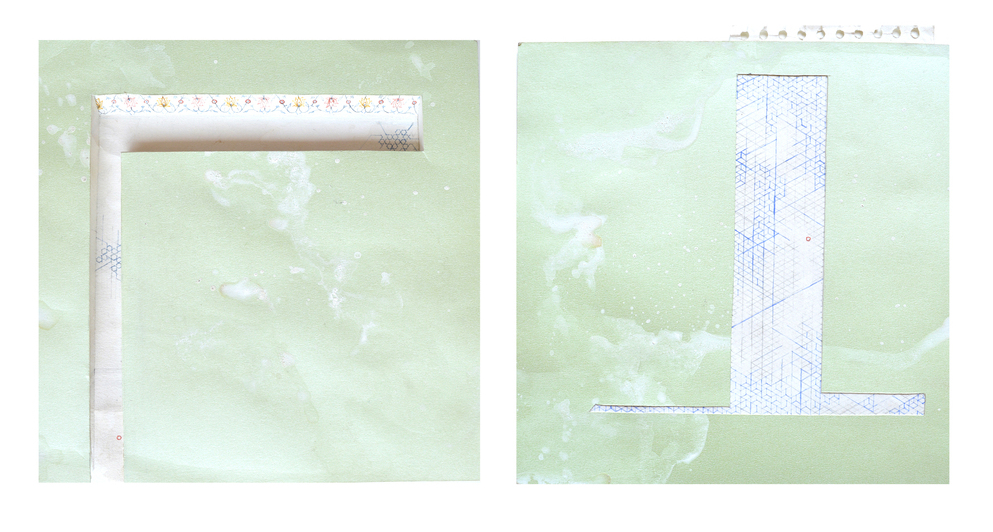

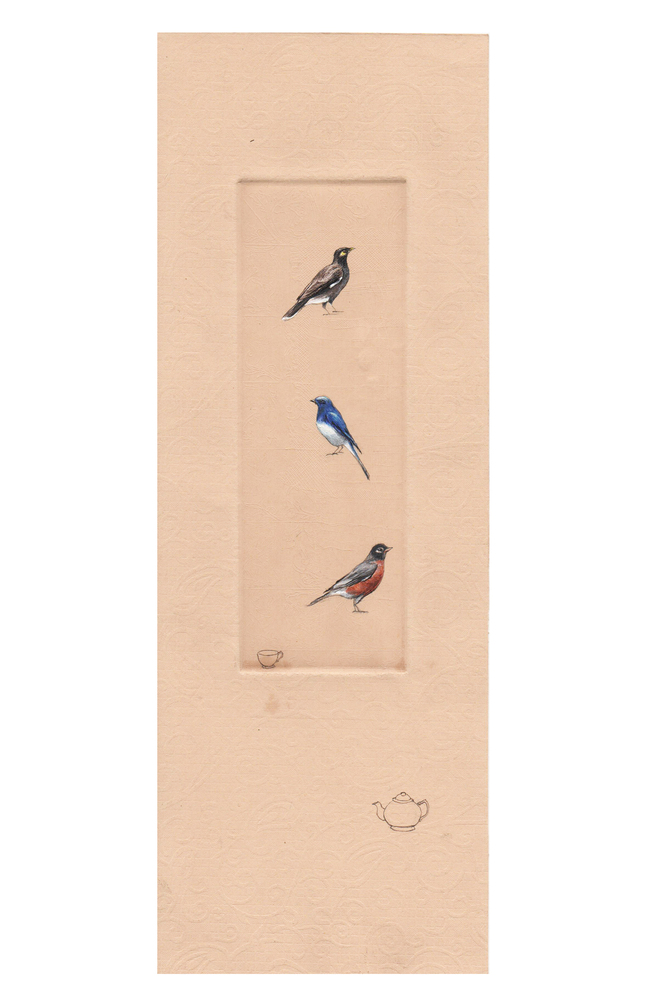

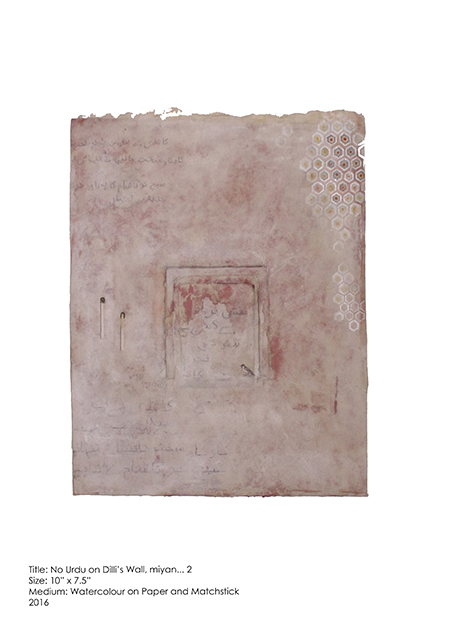

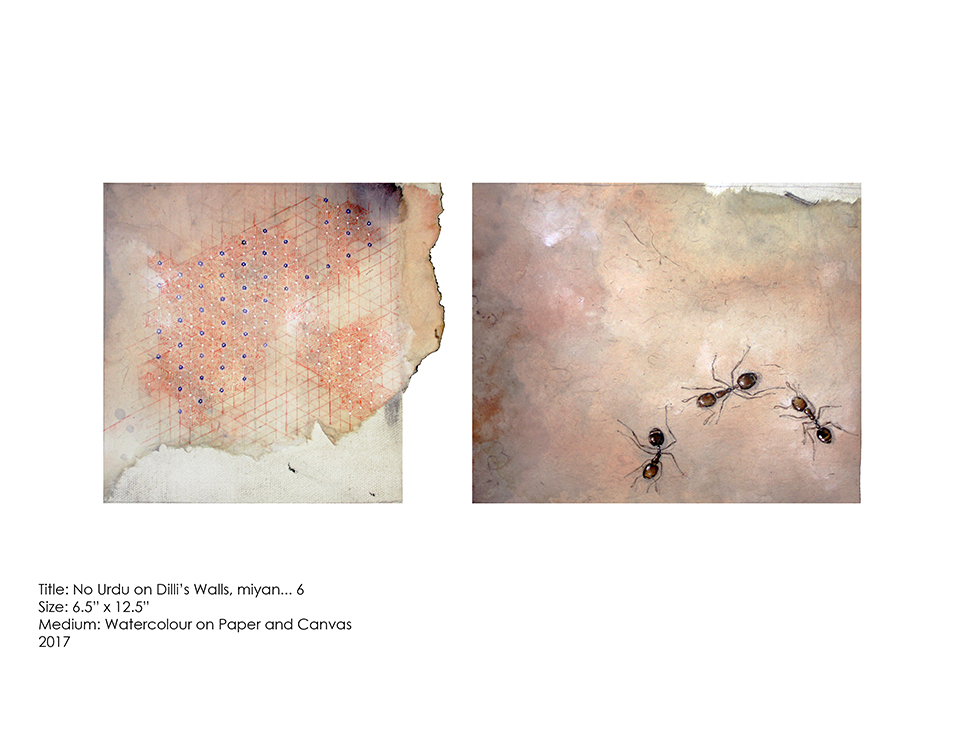

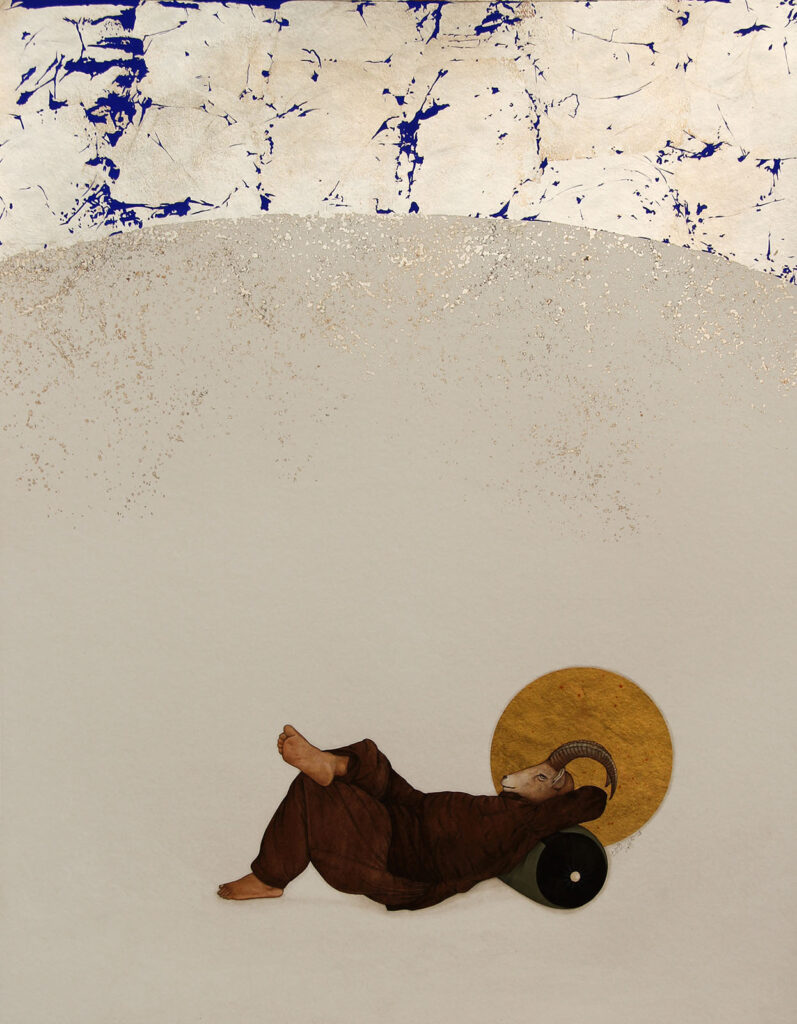

Dissensus brings together works by six artists who have been witness to the political and identity crises in regions of ongoing conflict — Nepal, Afghanistan, Iran, Kashmir in India and Pakistan. Even when the issues that are of immediate concern to them range from gender, territorial dispute, anxieties regarding cultural annihilation and ethnic marginalization, these artists withdraw into immediate, everyday contexts, and markers of cultural identity to construct quiet acts of dissent away from the central political stage. These intimate testimonies and observations employ the aesthetic to develop a micro-poetics of the stakes borne by civilians whose concerns are overlooked in media-narratives driven by political figureheads, capital and diplomatic ties. It is not coincidental that several artists find a language in the subtlety of the miniature tradition to voice their politics. Scale and detail evoke the marginal locations of their themes, and the multitude that is united in these narratives.

CURATORIAL NOTE

Chronicle of the Veil

“It seemed, sir, a woman, tall and large, with thick and dark hair hanging long down her back. I know not what dress she had on: it was white and straight; but whether gown, sheet, or shroud, I cannot tell.” — Charlotte Brontë, Jane Eyre

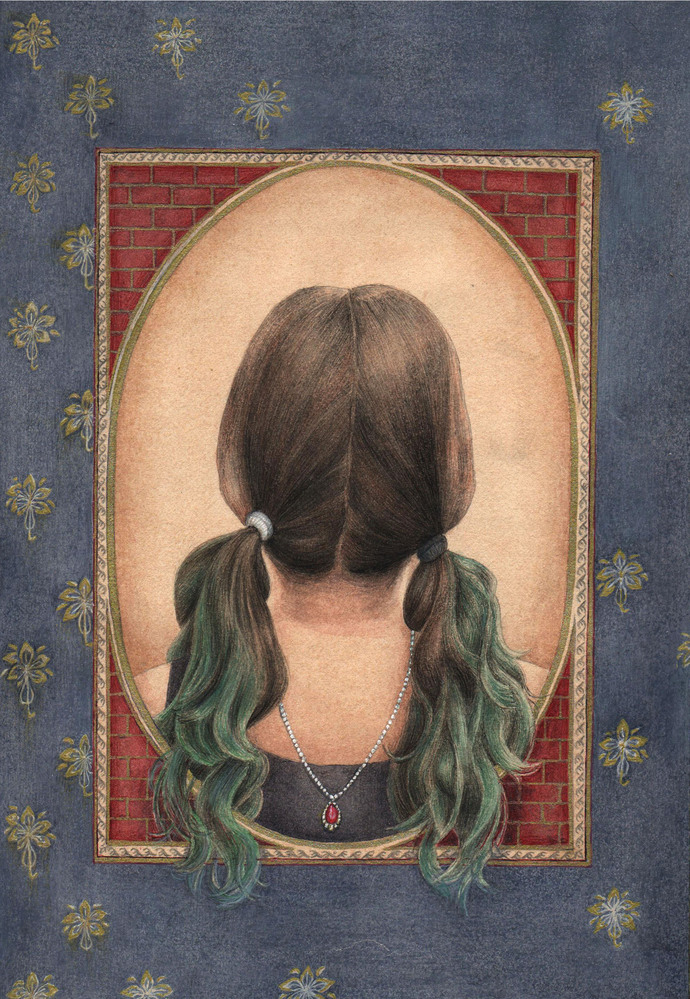

A woman, tall and large, wild and cackling mad — Bertha Mason, the iconic ‘mad woman in the attic’ from Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre, has become an epitome of Foucault’s madman, a metaphor for bodies on the line with revolting psyches, overcompensating for their systematized repression and functionalization in a society that relegates these to the margins of citizenship. The protagonist Jane Eyre recounts to her soon-to-be-husband Mr. Rochester the ‘visitation’ by the mad woman when “it removed my veil from its gaunt head, rent it in two parts, and flinging both on the floor, trampled on them.” The tearing of the veil becomes a gesture both symbolic and performative, and has been widely touted as Bertha’s (and by extension Jane’s) rebellion against the institution of marriage. The torn veil encapsulates the drama of a (conjugal) subservience-turned-haunting, and more generally a flinging in the face of the societal norms. The indistinguishability of the habit — whether gown, sheet, or shroud — and the anonymity it bestows, often an afterimage of disenfranchisement and removal to the collective blind spot, is subsequently weaponized by these marginalized bodies towards ends of socio-economic justice, autonomy and free self-expression. The borders of the ‘specular economy’ (the domain of the eye), thus transpire as sites where ignominy is repurposed by the alterity into an invisibility that grants them cover for their guerrilla warfare. The specular economy cultivates its own blind spots — forgotten folds housing colonies of the disbanded — allowing an alternative motley ‘socius’ to come into existence. From these penumbral recesses of the agentic wor(l)d, the invisible marches unforeseen, materializing as a ghost, an impersonator or a temptress, towards its goal of restitution. This narrates the interesting ballad of the veil from its invention in the specular economy as a contrivance for monitoring and subjugating certain bodies and their labour (physical, emotional, and reproductive) to its subversive deployment as a technique for seduction and treachery, its association with mysticism and adoption in the process of sublation. The opacity and materiality of the veil presides over its function, whether as a contraption for deflecting undesired gaze or as a trope in the Dance of the Seven Veils, as a shroud for the dead or a mantle for the denizens of the inglorious underground. The veil obscures and reveals, inures and allures, ennobles and defames, cloaks and kills, fetishizes and sanctifies, desubjectivates and empowers. One veil to rule them all!

Sur-veil-lance

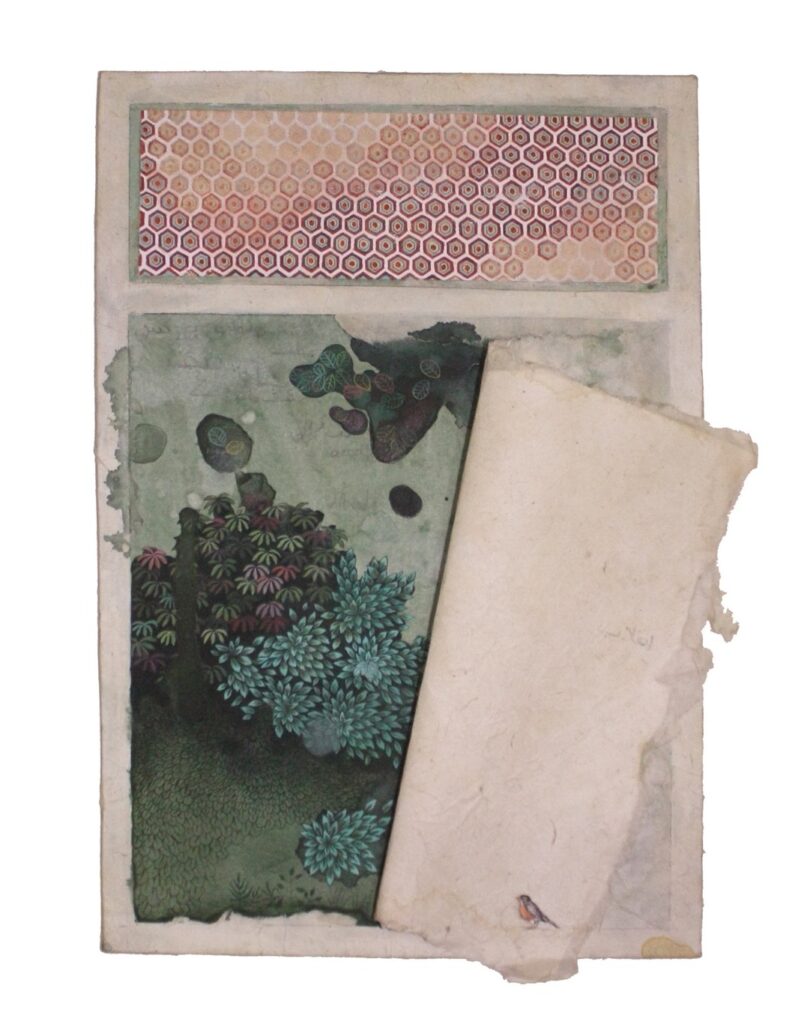

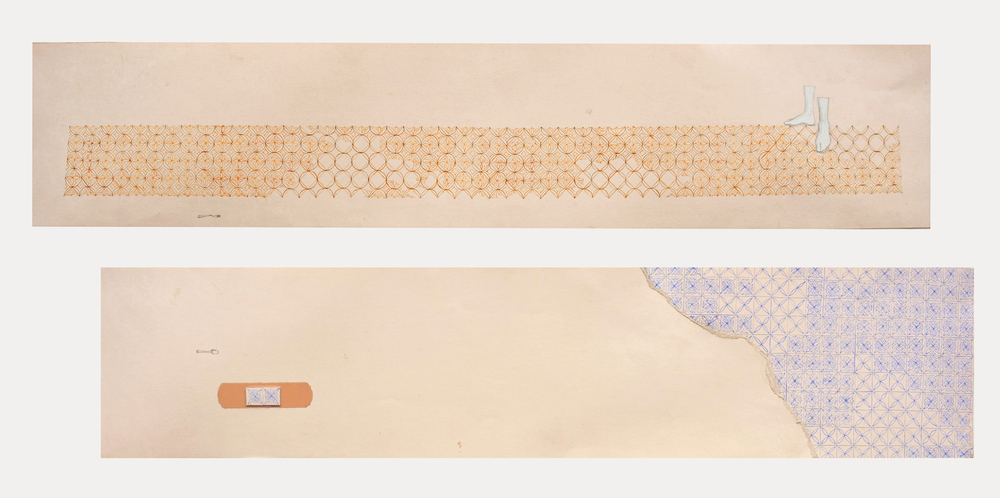

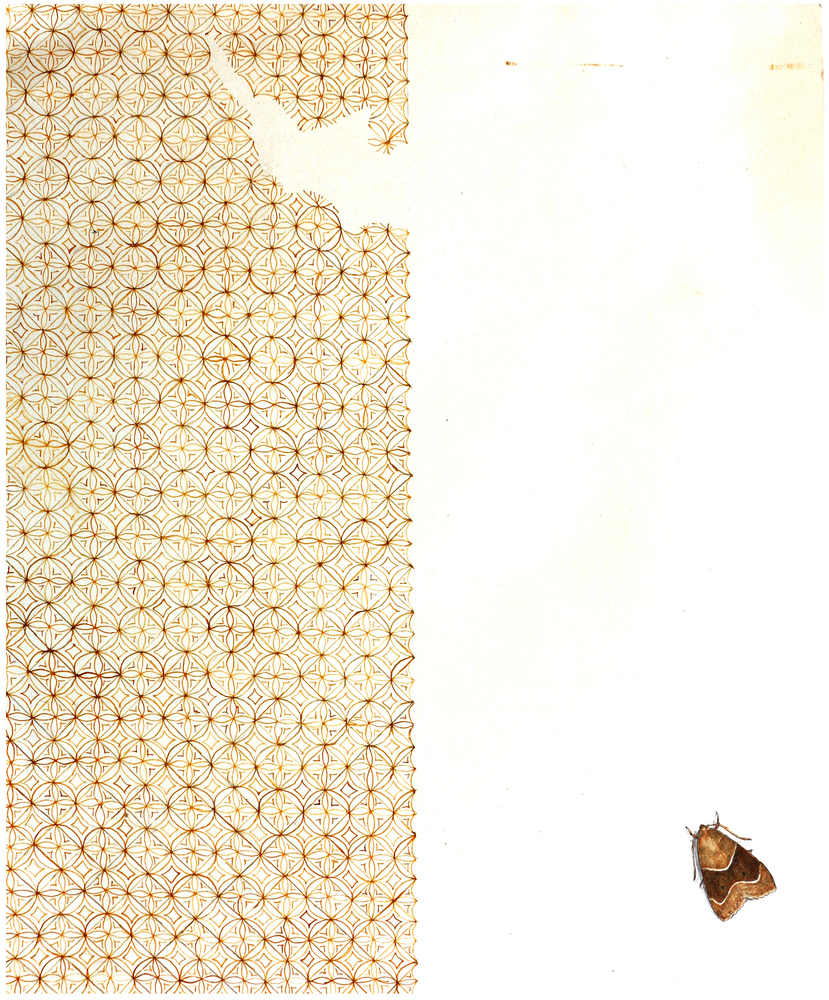

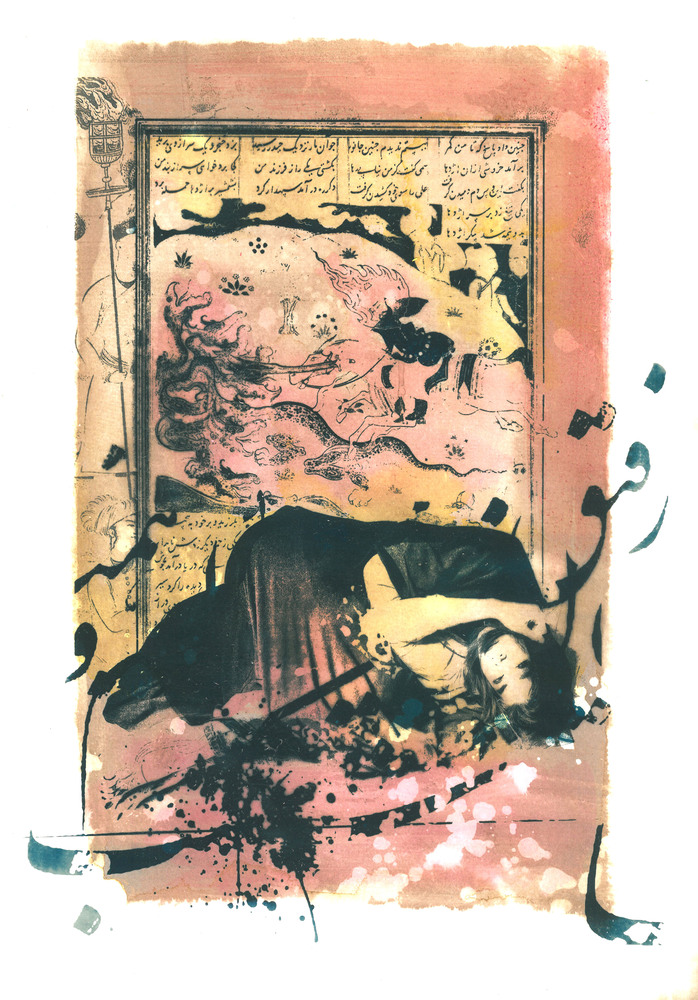

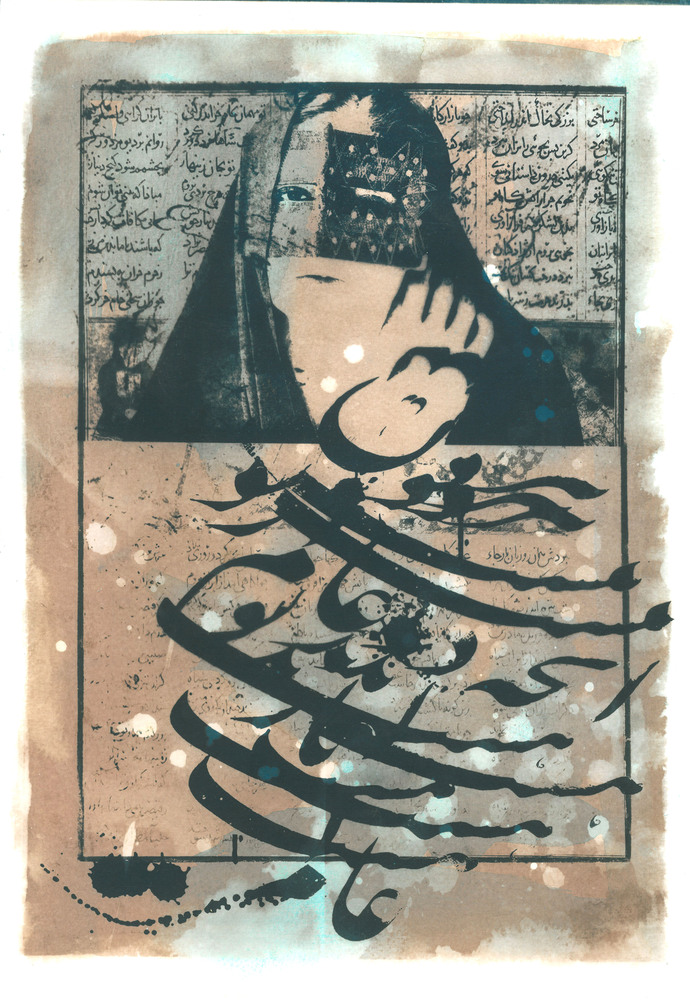

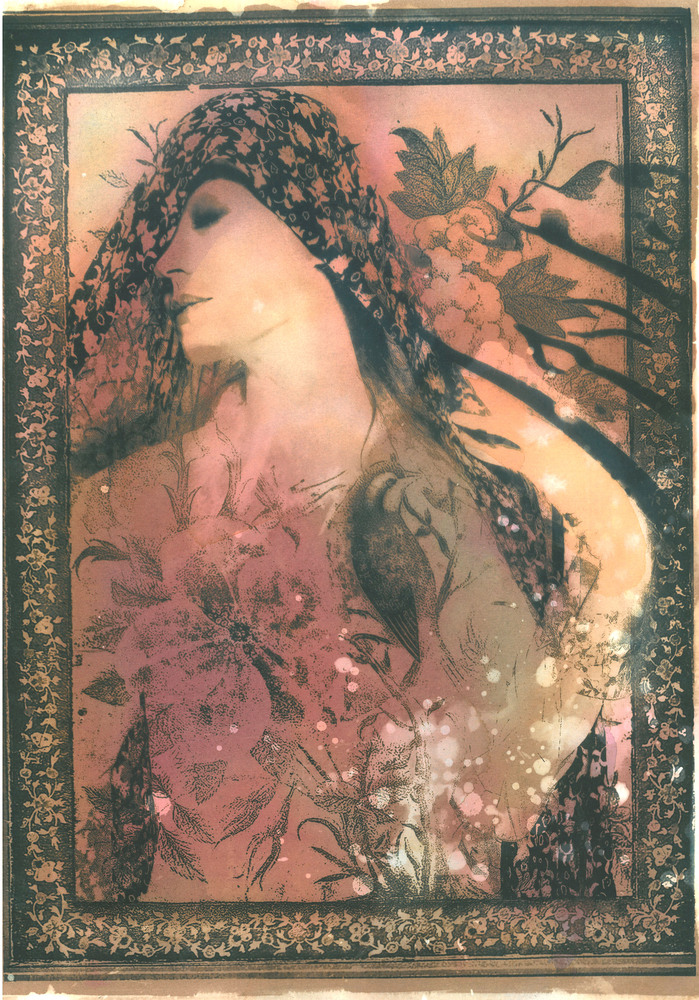

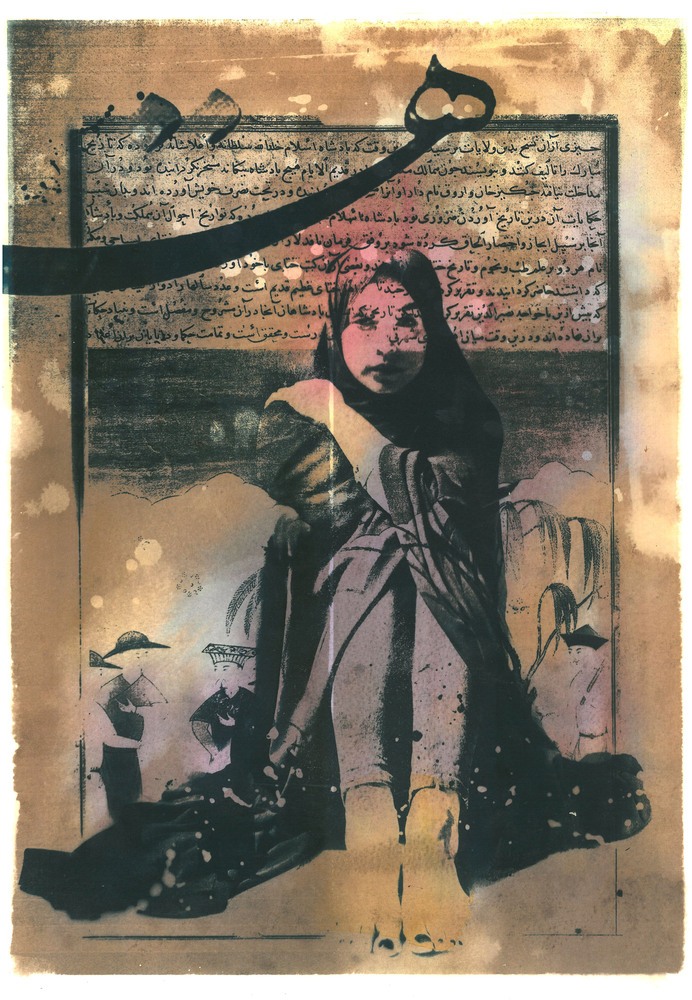

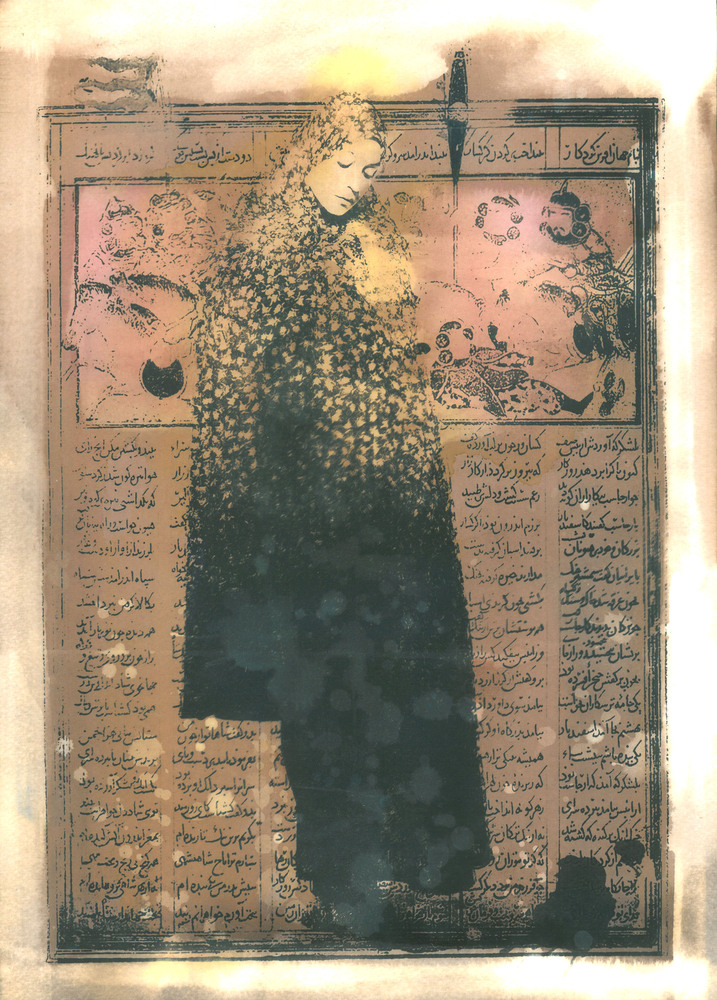

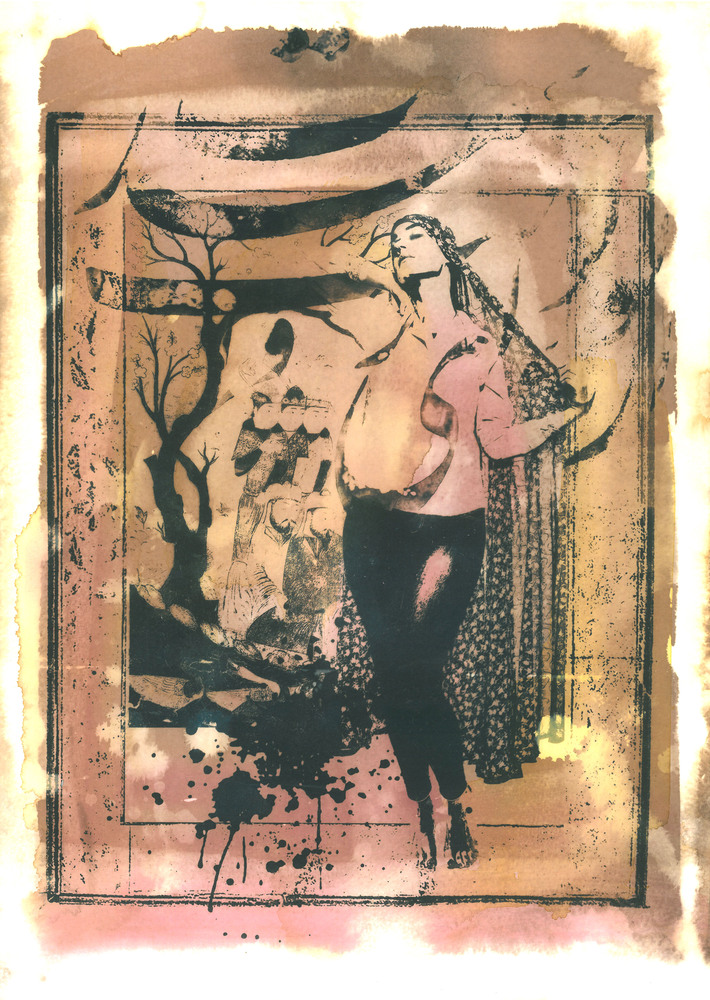

The current global political milieu characterized by heavy sur-veil-lance and censorship, has been hailed as ‘post-truth’ and ‘the new brutality’ pointing to a reductionist approach to criticality and the breakdown of civil discourse. In a treacherous turn, what we have been made to fear — anarchy — has been unveiled as a false enemy propped up by the institutions to consolidate their own position, protected and furthered through ever-constricting panopticism and hegemonic identity databases, as well as systematic gentrification and taming/curbing of critical forums. Anarchy, that could well stand for the self-reflexivity and dynamic vitality of a system, enabling discovery of viable avenues out of existential cul-de-sacs, has been turned on its head, to disguise the real enemy at work — the ossifying proclivities of neoliberal capitalism that seeks to foreclose all the alternatives and stamp out dissensus — betraying the truth of the foreboding words from Shakespeare’s Macbeth ‘Fair is foul, foul is fair.’ The Persian artist Neda Tavallaee tells such a tale of formalised censorship of women’s bodies in the Middle East, the strictures imposed on their autonomy and leisure, and the general accrual of mystery by these bodies when seen through a veil as well as their Orientalist exoticization as odalisques and Turkish bathers. These bodies have been ordered to the veil, both literally and symbolically, forcing them to seek new alliances and latitude within the extant configuration. Through her works, Tavallaee attempts to make visible these alternate economies and the beauty therein, as well as their struggles and predicament. In this saga of unsung heroes, foregrounded against the narratives of predominantly male prowess, such as the Shahnameh, that pervade Iranian culture, taboo on women’s bodies and expression meets everyday forms of resistance and small personal victories. The allusion to the grand legacies of the miniature tradition, serves both to enshrine these female characters, conspicuous in their absence from the annals of history, as well as underline the antiquated nature of prevalent accounts that fail to speak to the current condition. The series entitled About Havva (Havva being the Islamic name for Eve) is dedicated to an episode from 2016 that witnessed the unwarranted detainment of some Iranian fashion models active on Instagram. The models, under charges of indecency, were subjected to protracted interrogations, with advances made on their person, and released only after confiscation and destruction of their professional portfolios, phones and computers — all for the crime of beauty and being able to express it. The artist subsequently decided to collaborate with one of these detainees, encouraging her to share her story (art and poetry being few of the accepted mediums through which Persians are wont to expressing themselves) and even flirt with the chador (veil), the token of her subjugation. The model of Tavallaee’s cyanotypes, as with Waseem Ahmed’s burka-clad figure, seem to give the lie to the bullet-proof invincibility of the veil, by presenting a horrifying scene where certain bodies can be hurt, raped and silenced with impunity.

Iconoclasm

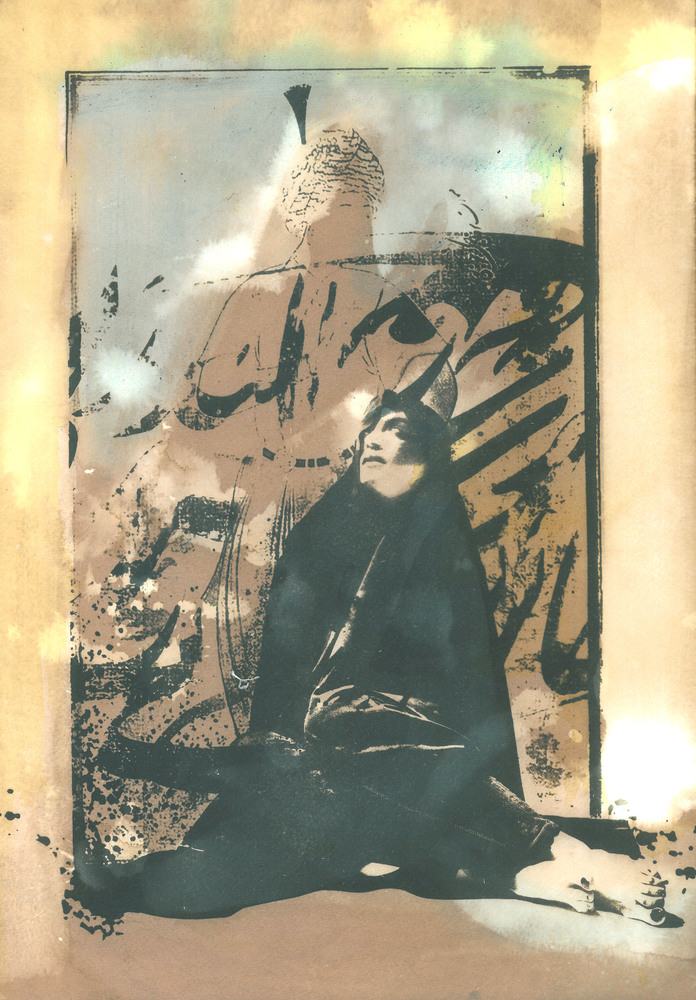

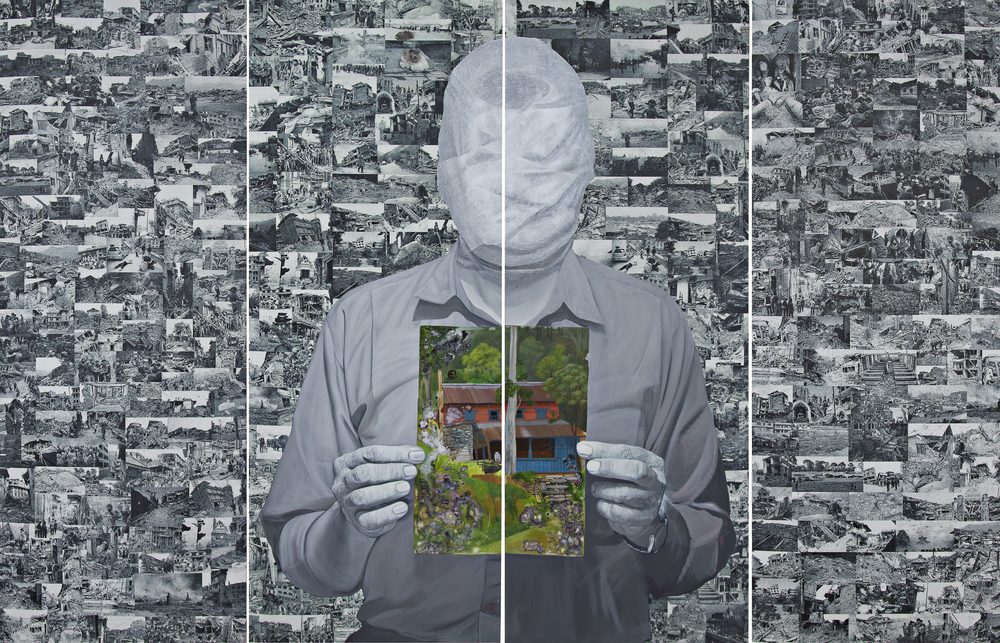

Obliteration of history is no mean task, the labour being long and arduous. Two stone Buddhas hewn into the side of a cliff in the Bamiyan valley in Afghanistan, stood vigil of the ancient Silk Road connecting China to the markets in the Middle East and beyond. Dating back to the fourth and fifth century CE, these monumental statues had become the identity markers for the region, firing the imagination of centuries of writers, with the figures being re-incarnate as mythical lovers Salsal and Shamama in the imaginary of the local Hazara. The restive majesty of the sculptures also attracted the interest of generations of iconoclasts, who sought to make a statement by bringing these low. First came the Mongolian hoards led by Genghis Khan, spelling havoc for the Hindukush valley but the Buddhas were somehow spared. This was followed by the 18th century attempts to destroy the statues by the Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb and the Persian ruler Nader Shah who subjected these silent sentinels to determined cannon-fire. The larger of the two statues, Salsal was partially defaced by the Afghan king Abdur Rahman Khan in the 19th century in a campaign to quell a Hazara rebellion. Nevertheless, the stolid figures continued to grace their niches more or less intact, at least till the turn of the millennium when the spectacle of their annihilation by the Taliban authorities was enacted and broadcasted to a stunned international audience. The Taliban Information Minister at the time appears to have bemoaned the slow pace of iconoclasm stating “this work of destruction is not as simple as people might think.” The longwinded process that comprised shelling these monolithic custodians of Hazarazat using a combination of anti-aircraft guns, artillery and anti-tank mines, and subsequently blasting them with dynamite and finishing off with a rocket, brings to mind the disproportionate, extended cruelty explicated by Gieve Patel in his poem On Killing a Tree.

Becoming Demonic

One might well ask, ‘What happened to the souls of Salsal and Shamama after their limestone bodies were smashed?’ One conjecture would be: unbeknownst to the spectators watching with burgeoning horror the tragic fate of the sculptures, the silent spirits finally unfroze and fled their cold corpses, passing into the surrounding Hazarazat where they found warm hosts in the much-persecuted Shia community that protested their wanton destruction by the Taliban. Their dislocation from the niches ensconcing them paved the way for their molecularization and universalization, and the subsequent commune of their agency through the Hazaras. The successful passage of the Bamiyan Buddhas into the Hazara ancestry was secured by a geographic proximity and cultural affinity, as well as a fractured mindscape susceptible to ingress by subjectivities alien/ inconsistent with the self. This outlines the basic tenets of demonology, identifying it as the science of a self divided, with its various dividends/claimants vying for local control. The demonic, thus transpires as a colonised self, harbouring foreign consistencies and contingently reorganised through anastylosis and bricolage. It materialises as a monstrous subjectivity, stitched together and animated like Frankenstein, where each assembled part is in colloquy with its individual past funnelled to the present. What renders a body ripe for possession is an exposure to violence, emotional vulnerability and an affective openness — attributes not uncommon with the social pariahs. Nor is it just the Bamiyan Buddhas that speak to us in this manner from the realm beyond the veil, but an entire hauntology of characters from literature, cinema, the antiquity as well as personal memoirs, that roam the psychological reaches of our gray matter as spectral presences out of joint with time. The study of humanities is a call for a volitional cultivation of the demonic that welcomes alien incorporation, and the artist in particular trains to be multiplicitous; a perfect vessel for channelling these possessive spectral clusters.

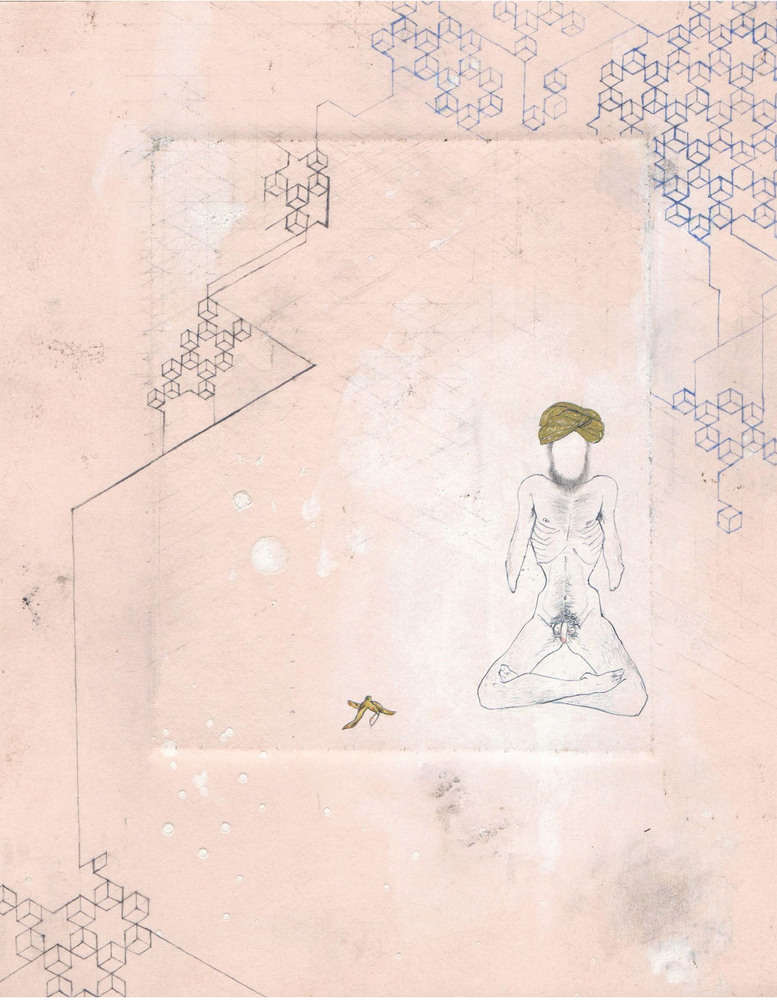

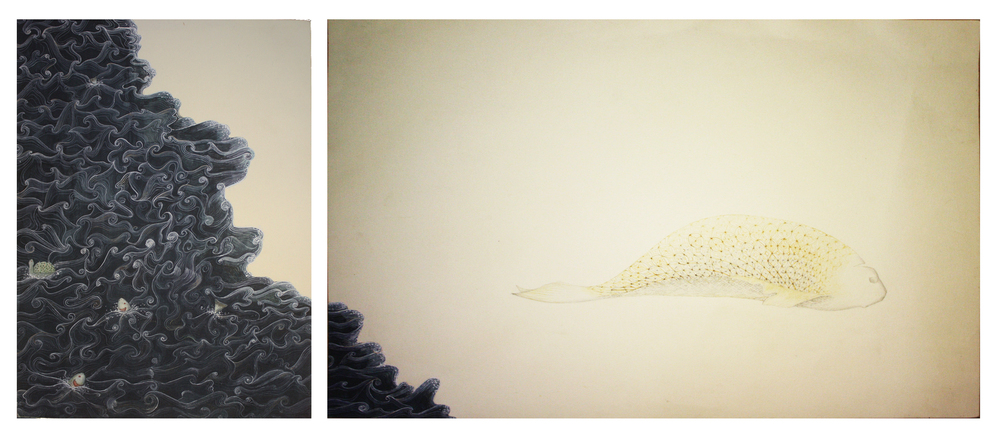

For the Night is Dark and Full of Terrors

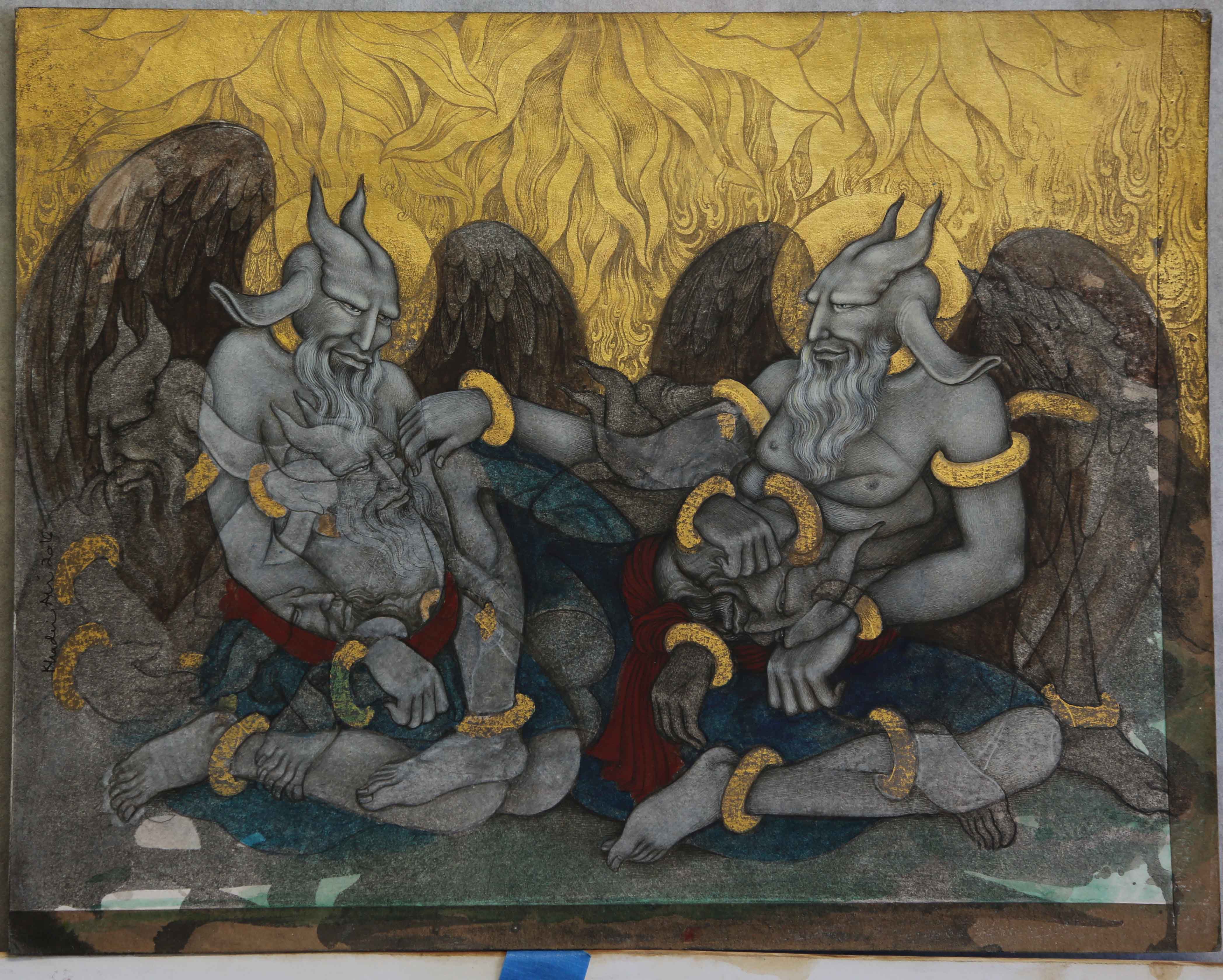

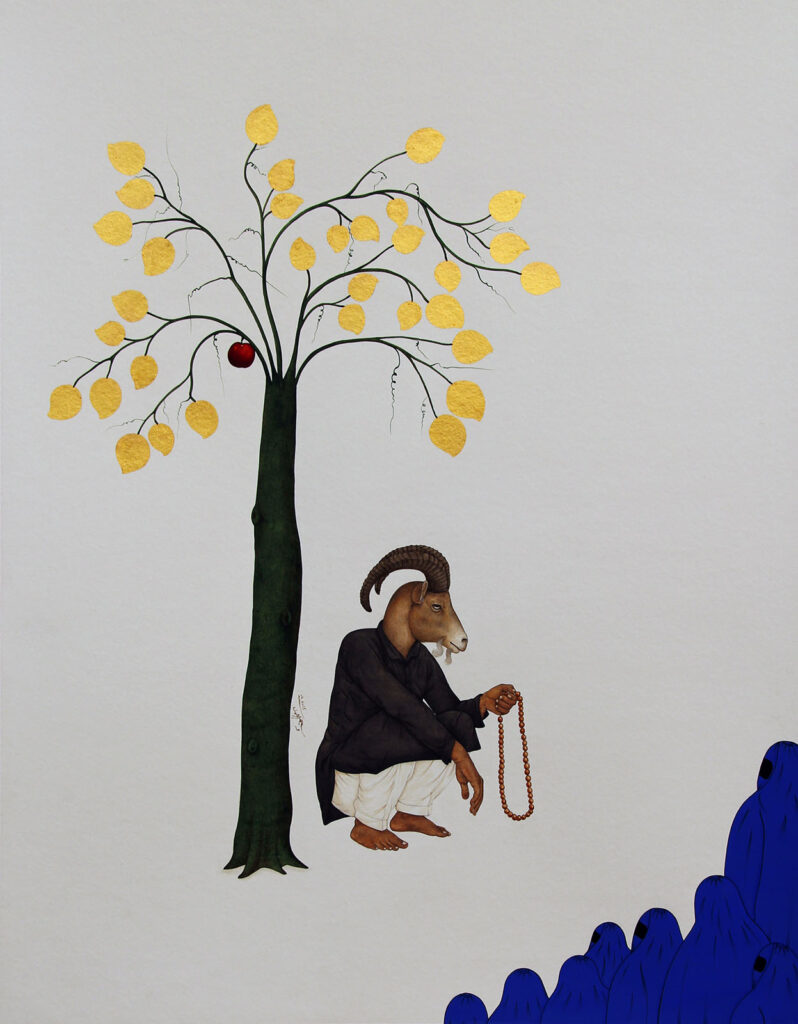

The Hazara artist Khadim Ali, like others in the exhibition, exploits the seductive aesthetic of Persian miniature painting to inflect contemporary concerns. Taking the 10th-11th century Persian epic Shahnameh as his point of departure, he presents a complicated characterization of the residents of its pages such as Rostam, Sohrab and Esfandiyar, much like the masterful Ferdowsi himself, tracing their persistence and renewed significance in present times. Are the ambivalent beasts of his paintings externalizations of a demonic psyche, disputed and stretched, usually found in an assembly of their kindred (or perhaps cloned selves), projected outwards to solve a dilemma? It is a case where all the external signs of an inner struggle have resolved into pot-bellied be-horned brutes, leaving their faces tranquil and wiped of worry, a conflicted person in reverse. Calmly, they converse about human foibles, the follies of war, the interchangeability of virtue and vice, and the trials of the refugees — the tense sombreness and perils of their parley betrayed only by a gesticulation here, a fire there. A previous series summoned the ghosts of the Bamiyan Buddhas to tell their story in resonance with still others: recent tales of iconoclasm such as the destruction of the Assyrian heritage by ISIL that has come to define a segment of global contemporary terrorism. The terror that a bearded or veiled figure inspires as well as the blind retaliatory racism it is met with, is a recurring concern with the artist Waseem Ahmed. In a previous work, the destruction wrought by the Taliban is contrasted with the curious case of the Vajrapani — a bodhisattva bound to the Buddha and encapsulating his power — whose violent aspect has been harnessed for the task of guardianship and protection. Another body of work addresses the demonization of the mulla who sometimes features in Ahmed’s work wearing a bomb-vest, in a projection of the unrest it harbingers. Violence, however, is not a factor of religion itself or of personal presentation, and can spring from any quarter: the artist wants us to remember. Both the psychopathic killer and the merciful saint reside within us, and this multiplicity and hybridity of being, the chimerical butcher-scapegoat/ animal-saint is revealed in the characters of his paintings.

Hauntology

Finally, with his installation Relics from the Lost Paradise, the Kashmir-born artist Veer Munshi seems to literalize the dictum ‘History is Alive’. Both the reliquary and the coffin are repositories/ resting places for the dead, with the difference that one is configured to the task of animating/ remembrance, the other with that of putting away/ forgetting. While contact with the contents of the former, is deemed salubrious and hence desirable, the thought of exposure to the contents of a grave would engender abject horror and repulsion. Both these objects are charged, albeit differently, with magical properties. One heals while the other haunts. Mobilizing the strong charge of abjection and grim consequence, induced by the imagery of a disinterred grave, the artist, in an emulation of the passion of Heathcliff, offers up for examination a war-torn and dismembered body of Kashmir as a corpus delicti, opening a space for meditation on the protracted strife and the larger question ‘why war?’ The audience is invited to take a walk through the graveyard of history and throw themselves open for possession by the undead past and the dying present in a corrective danse macabre. Often times, all that the dead want, is for someone to hear their story before the graph shifts from the paranormal to the normal again.

It all begins with an acknowledgement!

– Text by Adwait Singh